Era: 1790 - 1830 Cultural background: English Collection: Mitchell Library, State Library NSW Theme:Settlement

Collection

State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

Object Name

Portrait Miniature of Bligh.

Object description

Watercolour on ivory miniature in oval gilt frame. The miniature shows William Bligh in uniform of an Admiral. In the reverse of miniature is encased hair and pressed gold letters WB. The miniature sits in a mid-twentieth century, probably Freeman Bros. Sydney, miniature case. Dimensions: 60mm wide x 51 mm high.

William Bligh is perhaps one of the most notorious figures in Australian political history where myths and iconography abounds.

William Bligh was born on 9 September 1754 at Plymouth, England and as was usual for the time entered into service in H.M.S. Monmouth on 1 July 1762 at the age of 8. Bligh rose quickly through the ranks before being appointed Master of the Resolution on James Cook’s third voyage in the Pacific in 1776. In 1781 he married Elizabeth Betham, niece of Duncan Campbell, a shipowner who ran the convict hulks on the Thames River.

Bligh worked for Campbell on the West Indian trade until 1787 when he was appointed commander of H.M.S. Bounty to lead an expedition to collect bread-fruit in Tahiti for cultivation in the West Indies. This began his involvement with Sir Joseph Banks and New South Wales.

He was the only commissioned officer on the Bounty voyage with a very inexperienced crew. The expedition sailed on 28 November 1787 and reached Tahiti eleven months later. During their stay collecting breadfruit, the crew had grown to like Tahiti, the south Pacific lifestyle and many formed relationships with Tahitian women. The undisciplined and inexperienced crew preferred tropical island life over naval regimentation. Soon after departure for the West Indies on 29 April 1789, the crew led by Fletcher Christian mutinied seizing the vessel and cast off Bligh with 18 loyal crew members in a 7 metre open boat. Bligh astounded all when he navigated 5822 km to Timor in six weeks, charting part of the north-east coast of Australia along the way. This episode has made its way into historical folklore creating myths along the way.

After his return to London in 1790, Bligh was acquitted by court martial for the loss of his ship with the blame being squared with mutinous members of the crew. Regardless the myth was borne of Bligh, tyrant who brought the mutiny on himself.

Regardless of this episode the British Admiralty promoted Bligh to captain in 1791 to make a second attempt to transplant bread-fruit from Tahiti to the West Indies in the HMS Providence. This time the mission was a success. During this voyage he charted part of the south-east coast of Van Diemen’s Land at Adventure Bay, which he had earlier visited with Cook and with the Bounty. He made further valuable observations at Tahiti, Fiji and Torres Strait. This time he enjoyed the support of his crew however the strict water rationing Bligh imposed to maintain the breadfruit cargo created some discontent. This reveals a personality trait of Bligh of strict adherence to orders that would get him into strife later in New South Wales.

Between 1795 and 1801 he continued rising through the ranks of the Royal Navy seeing action in several sea battles including Camperdown as commander of the Director in 1797, and Copenhagen in 1801 where he earned the praise of Nelson for his command of the Glatton.

Later in 1805, Banks offered to secure him the post of governor of New South Wales to takeover from Governor Philip Gidley King, at double salary. Bligh accepted and sailed for New South Wales in 1806 leaving his wife behind to look after their five daughters and the family’s interests. His eldest daughter Mary and her naval husband, Lieutenant Putland, accompanied him to the colony. Bligh’s Instructions were to eradicate the rum trade and corruption in the colony which was widespread and enforce law and order.

Major Francis Grose, the Commander of the New South Wales Corps, became the acting Governor in 1792 when Governor Phillip left the colony. This effectively meant the New South Wales Corps ran the colony for their own benefit between 1792 and 1795 when Hunter, the former Captain of the First Fleet’s HMS Sirius, returned as the colony’s second Governor. The officers of the New South Wales Corps had become wealthy and arrogant in the meantime by developing substantial trade in rum and exploiting the local farmer settlers. The British Government was keen to understand and rectify this situation. Governor Hunter however failed to reign in the New South Wales Corps.

Bligh reached Sydney on 6th August 1806 and found New South Wales in a complete mess with a shortage of supplies at the Government store after the colony’s harvest was wiped out by the Hawkesbury floods, a shortage of convict labour to work the farms caused by convict transports diverted to supply the Napoleonic wars with France and a general malaise of the local economy caused by the corruption by the officers of the New South Wales Corps.

Bligh at once organised the distribution of flood relief and guaranteed settlers that the government store would buy their next harvest. Bligh then sought to wrestle back control from the New South Wales Corps. In 1806 he issued new port regulations to tighten up the government’s control of ships, their cargoes, including spirits, and their crews. Labour was scarce as no convicts had arrived in 1805 and only about 550 men in 1806-07. These actions increased the opposition to Bligh’s urgently needed reforms and brought him into direct confrontation with John Macarthur a wealthy landowner and former New South Wales Corps officer.

Bligh reissued the often broken order forbidding illicit stills, and outlawed the bartering of spirits for grain, labour, food, or any other goods and services. Everything had to be paid for with money.

The payment for goods and services in rum led to widespread drunkenness and debauchery. So in 1807 he ordered that all ‘promissory notes’ should be marked ‘payable in sterling money’. There was no New South Wales currency in the colony until 1813 and not enough British coinage to cover supply so any form of currency was used. The colony traded with Spanish, Portuguese and Dutch currency along with British coins. In 1800 Governor King proclaimed which coins could circulate in the colony and their value. These coins became known as proclamation coins

After most of the wealthy of the colony had come into conflict with the Bligh’s enforcement of the law, Major Johnston complained to the Home Office that Bligh was a tyrant and overstepping his authority. In return Bligh recommended that the New South Wales Corps be relieved as they were no longer required and had become corrupt, but not wanting to inflame the situation further he recommended not immediately.

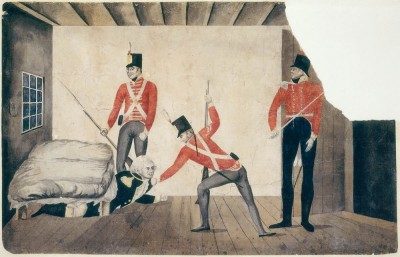

For two more years Bligh tried to control the New South Wales Corps. Essentially he wanted the officers and the wealthy to obey the same laws as the other people of the colony. In December 1807 Bligh had Macarthur arrested for breaking the law and disobeying regulations. The New South Wales Corps were furious. Macarthur’s trial on 25 January 1808 was a total farce with Macarthur ranting madly about the defence of liberty and property against tyranny. Major Johnstone theatrically warned of insurrection and imminent massacre. The next day, after hours of drinking, the officers of the New South Wales Corps decided to arrest Bligh in a coup d’état.

About 300 soldiers armed themselves and marched to Government House at Parramatta and placed Bligh under house arrest. Most of the population were apathetic and many of the Hawkesbury free settlers actually supported the Governor; but Bligh lacked the political skills required to manage the situation he was unable to garner this support.

The day after the coup the officers continued the drinking and celebrations when Johnstone took control of the colony. Johnstone was a stooge for Macarthur who ran the colony as his own fiefdom. Bligh was kept under house arrest at Government House for the rest of 1808. He spent most of 1809 in Hobart causing problems there meddling in the management of the colony until he finally returned to England in 1810 for Johnstone’s court martial. Johnstone was found to have acted improperly and dismissed from the army, but he was allowed to return to New South Wales as a free settler retaining ownership of his land and property.

Bligh went on to be promoted to Vice Admiral in the Royal Navy.

The Bligh watercolour is historically significant as a relic of this whole episode. William Bligh is perhaps one of the most notorious figures in Australian political history behind Ned Kelly and the Bounty mutiny and later his attempt to curb and control a lawless and corrupt New South Wales colony has borne many myths and conspiracies. Bligh’s legacy was to set a precedent for Governor Macquarie and the transformation of the colony of New South Wales from penal colony to a free settlement that would ultimately lead to the foundation of modern Australia. Despite the myths surrounding Bligh as a villain it the historical record that shows Bligh to be the opposite- a consummate Royal Navy professional with extraordinary naval, maritime and public administration skills. The grace and dignity in the watercolour is evidence of the reverence felt towards Bligh by the community at the time.

The Bligh watercolour has intangible significance to Australians as an a symbol of Australia’s brutal convict origins, the renowned corruption of the New South Wales Corps and the development of Australia’s political system.

The Bligh watercolour represents a time early in Australia’s history when the colony was still establishing itself and had become a lawless microcosm of rampant laissez-faire capitalism of the British Empire.

The Bligh watercolour has interpretative significance in the presentation of the story of the early nineteenth Australia, the foundation of Australian political culture, role of entrepreneurs and corruption in the establishment, survival and eventual expansion of the early colony at New South Wales. It also interprets an episode in the evolution from the brutal convict origins of European Australia to a migrant based market based economy.

Bibliography

Coupe, S & Andrews, M 1992, Was it only Yesterday? Australia in the Twentieth Century World, Longman Cheshire, Sydney.

Heritage Office & Dept of Urban Affairs & Planning 1996, Regional Histories of NSW, Sydney.

Heritage Collections Council 2001, Significance: A guide to assessing the significance of cultural heritage objects and collections, Canberra.

Hughes, R 1987, Fatal Shore, London.

Websites

Written by Stephen Thompson

Migration Heritage Centre NSW

July 2011 – updated 2012

Crown copyright 2011©