Era: 1840 - 1900 Cultural background: German Collection: Riverina Theme:Agriculture Folk Art Food Settlement

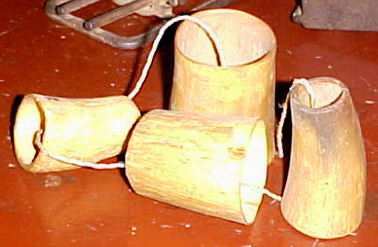

Set of 4 cow horn funnels, c.1890. Courtesy Museum of the Riverina

Collection

Museum of the Riverina, Wagga Wagga, Australia.

Object Name

Cow Horn Funnel

Object Description

Many German migrants living in South Australia and Victoria moved to the Riverina after the 1861 Robertson Land Act provided for the selection of land for £1 per acre. In 1858, the town of Holbrook was locally known as ‘the Germans’ and officially changed to ‘Germantown’ in 1876. Communities in the Riverina grew and prospered in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with the success of the wool and agricultural industries. Jindera, Walla Walla, Gerogery, Milbrulong, Henty and Trungley Hall also maintained Germanic populations, along with the townships of Jindera, Walla Walla and Henty.

The German settlers of the Riverina brought with them traditional domestic and craft skills, which had been passed down from generation to generation. Among these many and long established techniques were basket making, pottery, embroidery, leatherwork, woodwork, bread and pastry making and the manufacture of ‘small goods’ or sausage. These were not skills confined to the Riverina, but were part of the cultural construct of the districts in which German settlers had established their communities. For the groups that had spread throughout the Riverina in areas such as Jindera, Milbrulong, Temora, Trungley Hall and Holbrook by the late nineteenth century, these traditions had been brought from Germany and then via the Barossa Valley in South Australia where many of the settlers lived before moving to the Riverina in search of cheap land. The preparation and making of small goods or sausages is not confined only to German tradition, with the process being common practice among various cultures and nationalities of the Northern Hemisphere including Italy, France and Scotland.

The making of sausages was a long and involved process, beginning with the slaughtering of the pig and no part of the beast was wasted. Skills learned and perfected over many years were brought into action. The author and historian Colin Thiele describes in vivid detail his childhood in South Australia and memories of the pig slaughtering, which he recalls, ‘involved the whole family and demanded detailed preparation and frenzied activity. The gallows were always ready near the sty, withy hook, spreader and endless chain. Close at hand my father set up a row of four-gallon tins of boiling water and a special rack on which the carcass was to lie.’ 1

The freshly killed and bled pig was then covered with hessian and boiling water was poured over it, to soften the bristles on the skin. Home-made metal scrapers were then used to scrape away the softened bristles, leaving the skin clean and unblemished. After being hung clear of the ground and cleaned and dressed, the carcass was encased in a calico bag and left to hang from the ‘gallows’ to air and cool.

Little of the offal was discarded. Anything that was useful was sent over to the house to be cleaned and prepared for use the next day. My job was usually the cleaning of the intestines (or ‘runners’) under the stern supervision of my mother. These were the sausage-casings-to-be for Bratwurst. I stood on a box with a funnel, a dipper, and a bucket of brine, flushing the intestines again and again, turning them inside out and repeating the process over and over. It took a long time before my mother was satisfied that I had really done the job properly. 2

The following morning saw the butchering of the carcass, which involved a welter of cutting, sawing, slicing, mincing, mashing, salting, spicing and boiling, until every fragment of the pig had gone its allotted way.3 Various portions of the beast were set aside for salting or for immediate consumption or were exchanged with relatives and neighbours for other items of produce.

Sausage mincer, c.1890. Courtesy Museum of the Riverina

Hand operated meat mincers played an integral role in the preparation and making of the various types of sausage, which included the traditional German Bratwurst, Blutwurst and Leberwurst. Many of the recipes were passed from mother to daughter over many generations and the exact contents of the recipes were often closely guarded, family secrets.

Recipes for home-made sausages were also published in women’s magazines, with many ‘tried and true’ variations being exchanged among women Australia wide, through the home-help pages. Recipes which included sausages also came in a seemingly endless variety and included such delights as: Sausage Scramble, Toad-In-The-Hole, Curried Sausages, Sausage Fritters, Egg Sausages, Spanish Sausages, Windsor Sausage In Jelly, Imitation Bologna and Tomato Sausages.

Until the late 1940s, the making of home-made sausages was not an uncommon event, especially in rural areas. Advances in food preservation, including domestic refrigeration, changing perceptions and regulation of food hygiene and the promise of increased leisure time, saw the gradual demise of this traditional domestic skill, and increasingly, the purchase of sausages from butchers and later, supermarkets.

Recipes where swapped and published in the local newspapers, such as the one below.

‘Will you publish a recipe for making sausages and smoking sausages? Mrs. J.R.C. (Blackall)

To make beef sausages, take 2lb lean beef, 1lb beef suet, ¼ teaspoonful powdered allspice, salt and pepper, sausage skins, frying fat. Chop beef and suet as finely as possible; add the allspice, salt and pepper to taste. Mix well. Press the mixture lightly into the prepared skins.

To smoke sausages (N.B.: Our cookery expert has never smoked sausages, but the following is the correct way to smoke fish, and sausages can be done the same way). Take an old cask, and stop all the crevices, and fix a place to put a cross-stick near the bottom to hang the sausages. Cut a hole in the side near the top to introduce an iron pan filled with sawdust, and small pieces of green wood. Having turned the cask upside down, hang the sausages on the cross-stick, place the iron pan in the opening, put a piece of red-hot iron in the pan, and cover it with sawdust. Leave for 36 hours, keeping up a good smoke.’

Making and Smoking Sausages, Woman’s Budget 29 August 1930.

Set of cow horn funnels, c.1890. Courtesy Museum of the Riverina

These cow horn funnels are associated with the settlement of the Lockhart/ Milbrulong area by German families in the late nineteenth century. The funnels are associated with the raising and slaughtering of livestock, particularly pigs for domestic sausage making and the role played by women and children in the process.

No part of the animal was wasted after slaughtering and the cow horn funnels played a central role in the process of cleaning the pig intestines for use as sausage casings.

The cow horn funnels are also linked to the traditional skills which were brought to Australia by the German settlers.

The set of cow horn funnels are historically significant for its association with the settlement of the Lockhart/ Milbrulong area of the Riverina by German farming families. These immigrant families played an integral role in land clearing, farming and agriculture in the late 19th century.

Farming and domestic practices such as the raising and slaughtering of livestock and the economical use of the meat by-products in sausage making were a means to feed workers and families that continued traditional German farming and food preparation practices in the Riverina. Sausage making was for both domestic consumption and bartering within farming communities.

The sausage making funnels are associated with the domestic labour of women and children in farming communities and the practice of domestic sausage making, by the whole family, which continued until the late 1940s.

The funnels have interpretive value in demonstrating the process of sausage making and farming practices of German communities.

Footnotes

1 Colin Thiele With Dew On My Boots p34

2 Colin Thiele With Dew On My Boots p35

3 Ibid p35

Museum of the Riverina

August 2004

Edited by Stephen Thompson

Migration Heritage Centre

March 2006 – updated 2011

Crown copyright 2006 ©