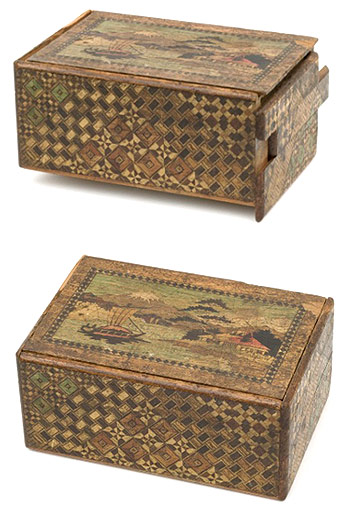

Era: 1939 - 1945 Cultural background: Japanese Collection: Australian War Memorial Theme:Boats Folk Art Games WW2

Japanese Himitsu-Bako puzzle box found in Midget Submarine by R Judge at Garden Island Navy Base, c.1939-1940. Courtesy Australian War Memorial

Collection

Australian War Memorial, Canberra, Australia.

Object Name

Himitsu-Bako Puzzle box.

Object Description

Plastic; Wood; Japanese inlaid rectangular wooden puzzle or secret box, featuring an interwoven geometric Yosegi pattern on all four sides and on the face of the hidden drawer; a traditional coloured inlaid scene of Mount Fuji with boat and house on the sliding cover; and a pink rose and bird design on the base and on the sliding lid of the hidden drawer, all using veneer wood. The lid is removed by sliding the top half of the proper right side panel, which releases it. This reveals a box, half the depth of the whole. Pulling up the proper left side panel reveals a sliding drawer fitted with sliding lid nestled in the lower half of the box. The drawer face is equipped with a small round orange celluloid handle. Dimensions: unknown.

Japanese Himitsu-Bako puzzle box found in Midget Submarine by R Judge at Garden Island Navy Base, c.1939-1940. Courtesy Australian War Memorial

Traditional Japanese puzzle box, possibly produced in the town of Hakone, and featuring an exterior design known as Yosegi – a series of intricate geometric glued veneer designs. In Japan these boxes are known as ‘Himitsu-Bako’ or ‘Secret Box’. The design on the lid is reminiscent of a woodblock print design and, as with many examples, features a scene of Mount Fujiyama with Lake Ashino in the foreground. There are five movements required to fully open the box. Some boxes were far more complex and might need up to 100 movements to open them. This example was discovered by a civilian boilermaker, Robert Judge in one of the Japanese midget submarines which was recovered from Sydney Harbour after the attack of the night of 30-31 May 1942. Judge was specifically employed at Garden Island, Sydney to cut open the submarines with an oxy-acetylene torch. He noticed this box as he entered the interior of the submarine, secretly removed it, and retained it as a keepsake. He was also asked to assist in removing the bodies from the submarine, and later welded his initials onto the nose of one of the subs.

Mini sub, possibly HA14, hauled from the Harbour near Bradleys Head. Courtesy Australian War Memorial

Newsreel footage of the aftermath of the raid

The Japanese mother submarines I-22, I-24 and I-27 left Truk Lagoon on 18 May 1942 and headed south between Rabaul and Solomon Islands. Each had a 46 ton midget submarine clamped to its afterdeck. Aubrey Brown told me that the three mother submarines had been detected by No. 23 Radar Station RAAF at Fort Lytton, in Brisbane as they travelled down the east coast. This provided some warning that an attack would most probably occur somewhere along the coast.

At 3.45 am on 30 May 1942, a Japanese floatplane, piloted by 27 year old Flying Warrant Officer Susumu Ito, was launched from submarine I-21. By 4:20 a.m. the floatplane, burning navigation lights, circled twice over Sydney Harbour near where the USS Chicago was anchored. It was initially thought to be an American plane but eventually some fighters were sent up to intercept the plane. Another plane was also reported at Newcastle. Neither could be found.

At sunset on Sunday 31st May 1942, there were five Japanese submarines positioned off the New South Wales coast near Sydney. Japanese mother submarines I-22, I-24, and I-27 launched midget submarines about 12 kms east of Sydney. I-21 and I-29 were the other two submarines supporting the attack on Sydney Harbour. The mini submarines were the HA-14, M-21 and M-24.

Submarine I-21 later took part in an attack of a different kind when it shelled Newcastle on 8th June 1942. On the same night Submarine I-24 also shelled the eastern suburbs of Sydney.

Ten shells fell in Rose Bay, Woollahra and Bellevue Hill but only one of the shells exploded. Courtesy Australian War Memorial

At 8 pm on Sunday 31st May the first midget submarine HA-14 made its way through Sydney Heads and was detected by an electronic indicator loop but was ignored due to other small boat traffic. The submarine became caught in the western part of the anti-submarine net. The Japanese crew detonated a demolition charge killing them selves.

At 9:48 pm M-24 entered the Harbour, following a Manly ferry through the boom defences. At 10:27 all vessels in the harbour were alerted of the submarines presence. USS Chicago spotted the M-24 and fired on it with tracers from its 20mm anti aircraft guns. At the same time M-21 was entering the harbour. Naval patrol boats Lauriana and Yandra tried to ram the midget and attacked it with depth charges.

At 11:10 pm HMAS Geelong fired at midget submarine M-24, just before it fired 2 torpedoes at USS Chicago. One exploded under an old ferry, HMAS Kuttabul, killing 19 sailors and wounding 10. The other torpedo ran up on to the shore and failed to explode.

HMAS Kuttabul after the attack. Courtesy Australian War Memorial

At 3:00 a.m., USS Chicago spotted midget M-21 which had been battered by depth charges as it entered the harbour. Several craft attacked it with depth charges. It was later found disabled on the harbour floor with its motor still running. The 2 crew had shot themselves.

The 4 Japanese submariners killed in this incident were cremated at the Eastern Suburbs Crematorium on 9th June 1942.

Prime Minister John Curtin allowed the Japanese Ambassador, Tatsuo Kawai, to take the ashes of the 4 submariners back to Japan after their cremation. Tatsuo Kawai arrived at Yokohama pier in October 1942 aboard the Kamakura Maru with the ashes of the four sailors in four white boxes. These four boxes had been placed on a large altar in front of a flag of the Rising Sun on board the Kamakura Maru during the journey to Japan.

Commander Matsuo’s mother came to Australia in 1968 and placed a wreath on the Sydney Cenotaph. She also visited Garden Island and the place where her son was killed in his midget submarine.

Midget Submarine M-24 was never found.

In 1943 Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the Japanese Naval Commander-in-chief, advised that Emperor Hirohito had granted a citation to the submariners in the attack on Sydney Harbour. The submariners had been elevated to “Hero God” status. They were all also all posthumously promoted by two levels of rank which meant a larger payout to the families of the Japanese heroes.

On Sunday 12 November 2006 seven scuba divers found M24 in 70 metres of water off Long Reef, north of Sydney.

The divers all met with the Director of the Naval Heritage Collection, Commander Shane Moore who has since confirmed that they had indeed located the missing M24 Japanese Midget Submarine. Commander Moore shared his knowledge of M24 and its submariners with the divers. He told them that Japanese tourists have often arrived at Garden Island to lay a wreath at the Conning Tower memorial near Woolloomooloo in Sydney. 60 Minutes produced a segment on the diver’s discovery which went to air on 26 November 2006.

Discussion between the Australian and Japanese governments will no doubt continue for some time before a decision is made on the fate of the wreckage of Japanese midget submarine M24.

Like the Cowra site of the Prisoner of War camp the mini submarines and their material culture remain as evidence of the inextricable and often tense relations between the West and Japan. Australia from colonisation has been suspicious and fearful of Asia, especially Japan and events such as World War II and the mini submarine attack on Sydney Harbour have concreted these attitudes. The Japanese migrant community have remained homogeneous and invisible, emerging to pay homage to those of died at Cowra and in the Sydney Harbour raid.

Japanese immigration to Australia began in the 1880s with the arrival of pearl divers and also of Japanese prostitutes. Most of the early Japanese arrivals in Australia were sojourners who had planned to return to Japan. According to Australia’s first national population census in 1901 there were over three and a half thousand Japan-born people living in Australia. However, most of the Japanese residents in Australia in the early 1940s were deported following the end of the Second World War. It was only with the arrival of the Japanese ‘war brides’ after March 1952 that a small resident Japanese community was established in Australia. Although approximately 600 Japanese ‘war brides’ were to gain entry to Australia, migration remained restricted for several more years.

In the 1980′s migration from Japan to New South Wales and Queensland increased as more skilled professionals were being recruited by Australian business. Now there are around 50,000 Japanese migrants living in Australia.

The puzzle box is historically significant as evidence of the midget submarine attack on Sydney Harbour and events the surround the relationship between Japan and Australia in World War II and afterwards.

The puzzle box has intangible significance providing a reminder of the fears felt by the Australian, Italian and Japanese communities of war, the loss of loved ones and the insecurity of war time. The mini sub attack is a focal point for both Australians of Japanese descent and Japanese nationals.

The puzzle box represents the Australian and Japanese experience in Australia during World War II. The puzzle box is associated with Australia’s long time racial fear of Asia that was amplified during World War II and racial antagonism to cultural minorities in wartime. The puzzle box represents a time when Australia was moving away from British foreign policy and becoming more confident of its place in the region but still held deep suspicions of non-British immigrants.

The puzzle box significance lies in its potential to interpret the attack on Sydney Harbour, humanising the mini sub crews and the Japanese experience and the fear and anxiety the attacks brought to an already racially fearful Australian community. The puzzle box presents the opportunity to interpret the stories of various individuals who were participants in major events in World War II.

Bibliography

Jenkins, D 1992, Battle Surface: Japan’s submarine war against Australia, Sydney.

Heritage Office & Dept of Urban Affairs & Planning 1996, Regional Histories of NSW, Sydney.

Heritage Collections Council 2001, Significance: A guide to assessing the significance of cultural heritage objects and collections, Canberra.

Websites

heritageaustralia.com.au/news.php?id=31&expand#view

Migration Heritage Centre

December 2007 – updated 2011

Crown copyright 2007©

The Migration Heritage Centre at the Powerhouse Museum is a NSW Government initiative supported by the Community Relations Commission.

www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au

Regional Services at the Powerhouse Museum is supported by Movable Heritage, NSW funding from the NSW Ministry for the Arts.

www.awm.gov.au