Lebanese migrants have been settling in Australia from the mid-19th century. By the 1880s sizeable numbers of Lebanese people were finding homes in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide. Download and read the Australian Lebanese Historical Society’s history of Lebanese communities researched in partnership with the NSW Migration Heritage Centre.

» Lebanese Settlement in NSW – PDF

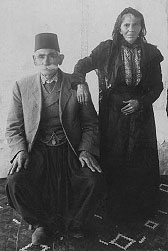

Abrahim Bookallil and his wife in about 1890. Photograph by Brien Iheup, Adelaide, courtesy of the Australian Lebanese Historical Society Collection. |

Because the first Lebanese arrived from the Ottoman district of Mount Lebanon in the province of Syria, they were called Syrians, or sometimes Ottomans. Until the formation of the modern state of Lebanon in 1943, the new settlers were rarely referred to as Lebanese, although some may have said they came from Mount Lebanon.

At the turn of the 20th century many Lebanese had settled in and around the Sydney suburbs of Redfern, Waterloo and Surry Hills. Some established retail and warehousing businesses and factories which prospered and provided employment for the newly arrived. Churches and other places of worship soon followed. An area centred on Elizabeth Street in Redfern became the economic and social hub for the community. The area became known as Little Syria and later Little Lebanon.

These migrants were not welcomed by the White Australia Policy which came into force in 1901 and held sway until the latter half of the 20th century. The policy originally favoured migrants from Britain and Ireland and required all to pass a dictation test in a language nominated by the immigration officer.

This new federal legislation effectively halted substantial Lebanese immigration because the Syrian/Lebanese were officially classed as Asiatics, until there was some relaxation of the policy in the 1920s.

Various official and social discriminatory practices prevented new arrivals from being employed. Lebanese Redfern warehousing businesses often gave new arrivals a suitcase of drapery, manchester and other small goods on credit to get them started. Without English language skills, and with little cash or education generally, they created their own opportunities when they hit the road as hawkers of fancy goods in suburban and rural areas throughout the State.

Small goods that could fit into the case were preferred: ribbons, material off-cuts, sewing needles and pins, cotton thread, thimbles, razors, handkerchiefs, underwear and other small items of clothing.

Many people remember as children their excitement when the Syrian hawker visited their out of the way property. Hawkers brought bibs and bobs to rural areas of NSW until the beginning of World War II. Once the hawkers gained experience in business and raised enough capital, they often opened shops of their own, still buying their stock from the Redfern warehouse men.

Relaxation of White Australia Policy regulations affecting the Syrian/Lebanese in the early 1920s and famine in Lebanon saw a second wave of immigration. Thousands arrived in Australia before the disruptions caused by World War Two halted immigration.

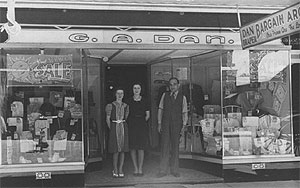

By 1945 almost every rural and urban centre in NSW had at least one Lebanese small business, and in many of the larger towns, small discrete communities of Lebanese appeared. They created a network of rural businesses.

Frequent trips were made back to the Syrian/Lebanese quarter in Redfern to purchase stock from the warehousemen, to attend to religious observance obligations and for social events.

It was important to Lebanese settlers in NSW that they maintain contacts with other members of their scattered migrant community in a way that allowed important parts of their culture to survive. Rural Lebanese families often met in central locations for weekend picnics where they could catch up on social gossip and exchange family and business news.

It is important that we record the early settlers and their involvement in city and rural businesses which were an important part of the economic development of NSW. These Lebanese migrants and their families worked hard and became respected members of local communities. Their children were educated locally and their involvement in civic life and the social activities of towns meant that they became solid members of their communities. Eventually, they were no longer seen as being foreigners.

Dan’s Shop in Gloucester, NSW, in the 1950s. Photograph courtesy of the Australian Lebanese Historical Society Collection. |

After World War Two more migrants began to arrive from Lebanon, some sponsored by Australian troops who had served there. The factories and workshops of city industries attracted them to make their homes in Sydney and larger regional centres and, of course, they continued to look for business opportunities.

Another wave, prompted by civil discord in Lebanon during the 1970s and 1980s came to establish a safe home for themselves and their families. They were supported by policies encouraging family reunions and multiculturalism.

A feature of Lebanese migration has been the attempt of the Lebanese to maintain contact with the Old Country, sometimes in the face of difficulties caused by distance, wars and economic disruptions.

Lebanese who have made NSW their home have distinguished themselves in business, science, academia, the professions, sport and the arts from the 1800s until the present time. From all records available, earlier Lebanese migrants shared – as do those of the later waves – a common desire with all migrants to build a better life for their families.

This Australian Lebanese Historical Society publication identifies and explore places in NSW where Lebanese immigrants have settled and acknowledge their integral role in the growth and development of the State.