(nee Miller)

English

Grimsby, Lincolnshire, England

Southampton, England in early May 1952

Sydney on 10 June 1952

Fairbridge Farm School village & farm, Molong, NSW (child migrant scheme near Orange) for 6 years

Doctor’s home, Parkes

Fairbridge Farm agricultural/domestic trainee

Domestic maid for doctor, Parkes; nursing in Parkes, Orange, Sydney and Bathurst.

I came from a large family of ten children in Grimsby, Lincolnshire in England. My father worked in a government job. We had a very happy home life – a nice, big home, plenty of places to play. My mother died when I was five; the youngest child was six months old and the eldest was not quite 15. We had large family support [and] were well looked after by the Catholic Church before and after Mum died. The church housed us, schooled and helped feed, clothe. We didn’t go without anything, we didn’t do any housework and then we hit Fairbridge [Farm in Australia], my God.

My father was not a Catholic. With the nuns owning the home and helping out, they had a big say. I think he [also] felt tied down by the children [and] wanted a different lifestyle. It wasn’t long after he retired.

When I was nine I remember going to a lady’s house, a lady he was fond of. It wasn’t long after the four youngest came to Australia. The fifth did come later because he missed the other children. The eldest girl left school, the others were still at boarding school.

I don’t remember being told anything, that he was giving us away. My father got on a train with us to London to Knockholt in Kent. We were assessed there and paperwork would have been finalised. It was a beautiful place, beautiful lawns, but it was nothing like what we were coming out to. No doubt that probably fooled a lot of parents.

We had to wear Fairbridge clothes, a grey suit. I don’t remember being told about getting on a boat and going over [to Australia from] I think Southampton. I just naturally assumed the boat was going to turn round and go back again. That was shattered as the journey went on. I sort of clicked that something else was happening because we had this lady that looked after our party of Fairbridge children. There was about ten [children], all different ages. Being kids we had a good time on the boat but even though I was only ten myself, [because] the youngest [sibling] was five, I felt I needed to look after them.

I had mumps and remember being put in a sick bay and a couple of the sailors brought me some nice fruit. I remember getting off at Port Said or Aden. I remember these little kids swimming in the water. Those poor little children; people would be throwing money to them.

We arrived on the SS Ormond on 10 June 1952. It took us five or six weeks. I remember getting a train all night to come to Molong from Sydney. Oh, it was horrific. It was so cold and kids trying to sleep, there were no beds. I am pretty sure that when we got [to Fairbridge Farm], it was more or less breakfast time and I vaguely remember [wearing] my grey skirt and blazer. We never saw them again by the way. They must have sent them back to send other kids in them.

I remember it was a freezing morning, there was snow on the ground. There was a fireplace but no fire. And there were kids on their hands and knees scrubbing floors. I couldn’t believe my eyes because I had never, ever seen anything like that before. It was awful. Honestly, I will never forget that day I got there. I can still see those kids on their hands and knees and how cold it was.

Because my little brother was only five, he was put in the same cottage as my younger sister and myself. But my other brother, who was about eight, he was put in another which I thought was a bit funny. The cottage mother lived on the premises in a room at the front. There was usually around about 13-14 children in each cottage.

Everything went by a bell. It was so regimental. This was a six o’clock rise, you had to strip your bed off; she was a bit of a fanatic, our cottage mother, for cleanliness. Then you started work on your floors or whatever you were doing, for a full hour. We [had] to scrub our benches and floors and [they] had to be white.

At seven o’clock another bell went and you had to walk down to the dining room where we all had breakfast. If you were primary [school] you did little odd jobs again; sometimes you had to go and pick up what we called ‘chips’ for the wood fires in the kitchen. When the cottage mother told me the first time [to] get the ‘chips’, I thought I was getting fish and chips! I had no idea.

Fairbridge School was for the primary kids, and I didn’t mind that school. The headmaster was a dreadful man but the other teachers were lovely, young people. You stayed until you were sixth class and then you went on the bus to Molong School. When we came home we all had to line up in front of the boss, Mr Woods. He would tell us what was what we had to do that evening. Most days we had what we call ‘muster’. You had to go and work picking burrs out of a field or stones. Some days we had sport after school; well we loved those. I was captain of the Fairbridge hockey team and our house team [at] Molong High.

When the ‘muster’ finished it was tea time. There was a cooked meal for the Fairbridge School children [in the] big hall. The ones that went to Molong had sandwiches [there] but when they came home they had the remains of what was left over from the kitchen. Well, our cottage mother never gave us that awful meal. On her day off she would often bring a cake home for us, something we didn’t normally get.

When I was about 14, I started to rebel. The cottage mother said, ‘You haven’t done that properly”. I can remember turning around and throwing the brush at her and saying, “Do it yourself”.

When you left school, about 15, you had to work on the farm. I was only small and some of the work, when I look back now, a man would find difficult. For a start you worked in the laundry and you had 20 baskets of washing; those clothes baskets were just so heavy. If you worked in the kitchen you had to set the cottage mothers tables up and serve. We worked in the people’s homes, like the bursar’s house. We had to do his housework, cleaning and washing. He had a wife and children but we had to do [it].

I can remember things happening to some of my siblings that I have never forgotten, not sexual, just beatings. I can remember my sister, Katherine, getting some beltings. When Reggie was only five, I can remember him getting a really hard slap because he was too little to get in the big bath. When he would have been about 12, I used to sit facing his [dining] table but he had his back to me. The cottage mother was right beside him and I saw her pick up a big ladle spoon and hit him. I remember getting up from the table, picking up that spoon and belting her with it.

My other brother, Douglas, and older brother who came out later, Hugh, went to a horrendous cottage [mother]. She had a whip, she was a drunk, she, never cooked them anything, she used to give them maggoty food. Our cottage mother, even though she was prone to violence and a temper tantrum, was good in other ways to us. But my younger brother, going to Mrs Newell [when he was older] was a godsend. She was good.

I don’t recall hearing anybody ever say “you did very well” or “something must have happened to make him like he is”. Everybody focused on “that naughty child”. Nobody showed you any love as such, but then I suppose with that many children, how could they? I do think the cottage mothers could not have been vetted because some were so vicious and horrible. Fairbridge kids didn’t show feelings; you never let them know how hurt you were.

We were the only Catholics at Fairbridge. The Molong nuns used to send us a taxi to go to mass. In those days you couldn’t have Holy Communion unless you fasted, so they cooked us the most beautiful breakfast. We loved it!

I was around 12 when Sister brought a letter to me from my great aunt Ellie. She was a nun in England. The letter [came] with a photo of my mother and this little card. The letter [had] nice things about my mother and even my father. The letter and photo meant a lot but the card didn’t at the time. It was only when I got older and I read what was on the back. It was about children being abandoned and exiled. I still believe to this day she was actually our real grandmother [and] was exiled because she wasn’t married when she had my mother. For punishment she was sent to the convent. I wasn’t allowed to keep the letter because Sister said if they find it at Fairbridge, they may stop [me] from seeing the nuns.

When I lived in England, I was a child. I was allowed to be a child. We played together, we went to school, we didn’t have to worry if someone was going to belt us. How can you compare a Fairbridge life where you got up by a bell, you made a bed by a bell, you got dressed by a bell and you went to eat by a bell? And you didn’t even eat in your own home? Then when you came back, you got on your hands and knees and you scrubbed and cleaned. That’s not a child’s life. My child’s life finished when I was ten. Reggie never had a child’s life, you know what I mean?

What they thought was wrong wouldn’t have been wrong if we had lived in society. We didn’t have any knowledge of the outside world. I wasn’t quite 17 when I left Fairbridge. I didn’t know how to conduct myself. I didn’t know anything about money. I didn’t know how to behave in front of other people. Social contact – I didn’t know anything about it. Suddenly you are thrust into this society where there’s shops, responsibility, banking, dress codes. I did not know how you got babies. This is no word of a lie. I honestly didn’t until I went nursing.

Fairbridge found me this doctor in Parkes who worked me like a horse for his home, wife and family. When it was bedtime on my first night I remember I cried and I cried and I cried. Never have I ever felt so lonely. You come from this place where there is all these kids. You play with them, you toil with them, you cry, you fight. Then suddenly you are stuck in this place, nobody there to talk to, and it was just the loneliest feeling I have ever felt. I was leaving my siblings behind as well and I thought I will never see them again.

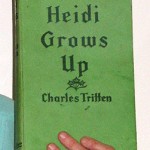

I got sick a lot. I worked hard at Fairbridge but it was continuous at this place. When I was sick I used to [go] to the surgery next door. One of the doctors was such a kind, gentle man. He said, “Would you like to be a nurse?” I don’t think he had time to get it all out before I said, “I would love to”. I worked at Parkes Hospital as a trainee maid and then I was a nursing assistant. It was a completely different life altogether. I got a decent wage, I had freedom, I worked eight hours. Then I was an enrolled nurse in Orange, was in Sydney for some time, and eventually went to Bathurst University and did a mental health project there.

I married and had two girls but that marriage ended. Then as time wore on, I went back nursing. But, yes, it all worked out well. The girls are good, they married well, they have nice children. But to be quite honest I think you always carry that baggage. Some people you think you may be able to trust might let you down again.

We never lost contact with the other siblings that stayed home, but when we first met them, they couldn’t understand why we were delving into family. They remember our mother being at home, whereas I can never remember my mother holding me.

None of us ever forgave our father. He was retired and came to see us several times. The first time he was at Fairbridge for six months [after] five or six years [there]. But it was too late. I had no feeling for him.

He actually stayed with me before he died and still wouldn’t tell us the truth about family. I wouldn’t throw him out or anything. I wouldn’t dare do what he did to me or the younger ones. But he was never a father. I told him once, “If there is a heaven, our mother would be crying every day still for what you did, because you gave her children away”. I remember that.

Interviewed by:

Andrea Fernandes, NSW Migration Heritage Centre on 5 February 2007

With assistance from Ian “Smiley” Bayliff and David Hill.

Visit the Fairbridge Heritage Project page for information on the CD-rom, The History Of The Fairbridge Settlement, Molong, by Ian “Smiley” Bayliff and David Hill and the publication, The Forgotten Children, by David Hill.

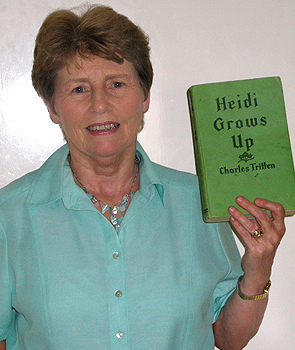

![[Clockwise from top left:] Siblings Reggie, Katherine, Douglas and Gwen in their courtyard at home, Grimsby, England, 1952 [Clockwise from top left:] Siblings Reggie, Katherine, Douglas and Gwen in their courtyard at home, Grimsby, England, 1952](../../../cms/wp-content/uploads/2008/09/kids.jpg)

!["I was around 12 when Sister brought a letter to me from my great aunt Ellie. The letter [came] with a photo of my mother and this little card. The letter and photo meant a lot but the card didn’t at the time. It was only when I got older and read the back. It was about children being abandoned and exiled."](../../../cms/wp-content/uploads/2008/09/holy-150x150.jpg)