PLAGUES, PANDEMICS AND BRIDGES

‘A heap of Rats’ from Views taken during Cleansing Operations, Quarantine Area, Sydney, 1900, Vol. V / under the supervision of Mr George McCredie, F.I.A., N.S.W, Courtesy State Library of New South Wales

Bubonic plague broke out in Sydney in 1900 and soon spread to other Australian states. In seven months, 300 people caught the disease and 100 died. The disease came to Australia on ships from other countries, so the area around Sydney’s docks was quarantined: people could not move into or out of the area. The plague was spread by rats so the New South Wales Government introduced a rat bounty to encourage their capture.

In January 1919, a worse epidemic broke out. The Spanish Flu, brought to Australia by soldiers returning from World War I, killed millions of people around the world. Between 1919 and 1920 it killed more than 11,500 Australians. Fortunately, the Commonwealth Government was prepared and was able to stop the epidemic from spreading. Public health measures were introduced and an infectious diseases hospital was set up at Long Bay in Sydney. Quarantine stations were upgraded to quarantine and treat migrants and sailors suspected of carrying the Spanish Flu and other diseases.

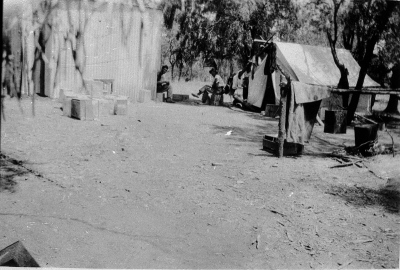

Soldier Settler camp Curraview at Naradhan, New South Wales, 1924. Courtesy State Library of New South Wales

Soldier Settler Scheme

As soldiers returned home from World War I, many found there were no jobs and affordable accommodation. The Australian Government believed the soldiers deserved something for their war sacrifice and set up the ‘Soldier Settler Scheme’. State Governments provided land for soldier farms and the Australian Government provided funds to get them started. In New South Wales, most of the land was in the Riverina district, ironically an area that had large German communities before the war. Some soldier settlers did well, most did not. Over 37,500 took up farms, but by 1929 almost half had given up and left their land. The main reason for failure was their lack of farming experience, coupled with a long drought and falling prices for farm products. Italian migrants brought farming knowledge and practices with them, introducing irrigation and wine making to the Riverina area and turning the abandoned farms into successful businesses.

In the 1920s, the Australia Government was keen to develop regional areas. Prime Minister Stanley Bruce considered there were three things necessary for this: labour, money and markets and for these Australia depended on Britain. British migrants were encouraged to settle in Australia. The Australian Government paid most of their fare and, like the soldiers before them, some were assisted to establish farms. Unfortunately, also like the soldier settlers, they had come from urban areas and had limited or no experience in farming. As a result they failed and many abandoned their farms. They were told they would do well in Australia, but they were not told about the problems they would face, like finding a job, a home and settling down in a new country. About 212,000 migrants came from Britain and most ended up in cities.

An original Anzac and his family evicted from their Redfern home into the street during the Depression, William Roberts, 1929. Courtesy State Library of New South Wales

The Government needed substantial sums of money to fund these programs, as well as to pay for war pensions and the Soldier Settlement Scheme. It needed capital to build railways, roads, schools and hospitals and to supply houses with electricity and water. It needed money to pay the interest on the loans it had taken out during World War I. During the 1920s, the Australian Government borrowed heavily from British banks, who along with arms manufacturers were the main beneficiaries of the war.

In 1920, established farms and factories produced more than they ever had before. There were fewer than 6 million people in Australia, far less than were able to consume this excess in production so it was essential for goods and produce to be exported overseas. Australia had to find new overseas markets to sell them. The Dominions of the British Empire made an agreement to exclusively trade between themselves. Dominions would enjoy lower customs charges on imports and exports and this helped make the goods cheaper to buy in the shops. Britain continued to buy most of Australia’s wool and wheat.

Children line up for a free issue of soup and bread during the Depression, c.1932. Courtesy State Library of New South Wales

The Great Depression

For many people the ‘Roaring Twenties’ were good years. But by 1929 the world economy began to slow. Rural product prices were falling and farmers found it hard to sell their produce overseas. In the cities, businesses found it harder to sell their goods overseas. As production slowed, workers were laid off and unemployment hit 10%. For migrants and soldier settlers already experiencing hard times, this made things worse. In 1929, the economy stalled in what is called the ‘Great Depression’.

The Great Depression started in the United States. In the 1920s, the United States economy was booming and a large number of people invested all of their savings in shares on the stock market. A lot of investors made fortunes, but in 1929 investors panicked and began selling their shares in mass hysteria. As a large number of shares were sold, share prices plummeted. As the share price fell more people panicked which set up a self-sustaining cycle. On 24 October 1929, the stock market crashed and shares became worthless. This event impacted on the supply of money to countries all over the world.

In the 1920s, the United States and Britain were the world’s largest investors in overseas projects. By 1930, the United States stopped investing in other countries, demanded that other countries repay loans owed to it, put up high tariffs on imports and cut back on imports. Britain owed the United States a fortune in loans and called on Australia to pay back the millions of pounds it had borrowed in the 1920s. But Australia had no money either. As people lost their jobs, they could not afford to buy goods or pay taxes. It was mainly the unskilled workers and their families that were hit hardest and this included the recently arrived migrant families who were already finding the going tough. Shanty towns sprang up at Blacktown, Sans Souci and La Perouse. People vowed this would never happen again and the Australian Government took over social welfare in the 1930s.

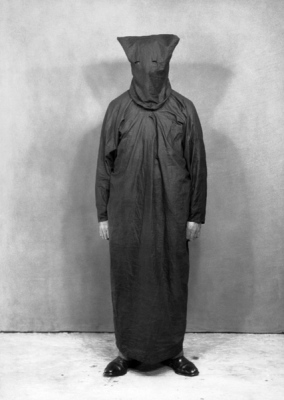

The costume of an inner fascist group in the New Guard, c.1930s. Courtesy National Archives of Australia

This economic disaster encouraged people to join political organisations that promised solutions to their problems. In New South Wales two of these were the ‘Australian Communist Party’ and the ‘New Guard’. These groups reflected the rise of communism and fascism in Europe and their ideas came to Australia with migrants. Many of the organisers in the trade unions were migrants from northern England and the intellectual left in Australia came from German Jews migrating from the persecution of the Nazis in the 1930s. Most of the New Guard were ex-soldiers from the Great War who saw solutions in militarist terms. They wanted a strong government to take charge and round up troublemakers. Some New Guard branches took the black on red swastika flag of the Nazis as their symbol.

By the late 1930s, the economy started to recover with people getting jobs and factories producing more goods. But the Great Depression had produced a lot of suffering and had important effects for Australia. Between 1930 and 1939, Australia’s development almost stopped. The productivity of farming and industry declined. There was almost no migration to Australia and fewer babies were born between these years. Many people had lost faith in the Australian Government’s ability to manage the economy.

Sydney’s Bridge

Growing out of the gloom of the Great Depression, the Sydney Harbour Bridge came to symbolise Australia’s hope for a better deal and fairer future for all.

Work on the bridge started in 1924. Over 720 homes were demolished and whole suburbs of the Millers and Milsons Point changed forever. The main arch was started in 1928 and Sydneysiders watched the two halves rise to meet on 19 August 1930. To many people the bridge was one of the wonders of the modern world.

Proposals to join the north and south sides of the harbour with a bridge were first put forward by convict architect Francis Greenway in 1815. There had been many plans to build a bridge across the harbour through the 19th century, but none were realised. This was because it was very expensive and the technologically difficult to build bridges over large areas fast flowing water such as Sydney Harbour.

After holding a worldwide competition in 1922, the New South Wales Government received twenty proposals from six companies. The English firm Dorman Long and Co of Middlesbrough won the competition and the contract for £4,217,721.00 was awarded on 24 March 1924.

The bridge was opened in March 1932. New South Wales Premier Jack Lang made the opening speech, but before he could finish Captain Francis de Groot of the New Guard rushed forward on horse back and cut the ribbon in the name of the decent citizens of New South Wales. He was promptly arrested as a public nuisance.

A new ribbon was located and Lang opened the bridge. School children, bridge workers, politicians, bureaucrats and Aborigines specially selected for the occasion marched across the bridge in a huge procession. Even Bondi Lifesavers paraded across in formation burning their feet on the hot bitumen. A newsreel commentator announced it makes you proud to be Australian.

At the end of the ceremony the public were allowed to swarm over the bridge before it was opened to evening traffic. The day ended with a spectacular fireworks display.