Era: 1840 - 1900 Cultural background: Afghan Collection: Broken Hill City Council Theme:Archaeology Economics Exploration Federation Folk Art Settlement

Former mosque relocated from the Afghan Camp and later the cemetery in Broken Hill, 2010. Photograph by Bronwyn Hanna. Courtesy Heritage Branch, New South Wales Department of Planning.

Collection

Broken Hill City Council, Broken Hill, Australia.

Object name

Broken Hill Mosque Collection.

Object Description

The mosque is constructed of corrugated iron sheets and wood painted rust red (which is the colour of the original mosque and a typical colour of Broken Hill). It is in fair condition. The adjoining anteroom is also constructed of the same materials. The mosque sits on a dusty site with an avenue of date palm trees which were planted in 1965 by the Broken Hill Historical Society. At the entrance of the site are two olive trees which were planted by the Islamic Council of New South Wales in December 2008.

On the site there is the collection of original camel wagon wheels, made from wood and iron, camel bells, nose pegs, photographs, stepping stones, camel saddles, traditional female and male headgear from Baluchistan a walking stick that belonged to the last Mullah along with other items associated with the Islamic religion.

Near the entrance to the mosque is the water trough used by the men to wash their feet before they entered. Upon removing their footwear the men stood beside the concrete channel as water was poured over their feet. The specially constructed stepping stones used to enter the mosque are now housed in the anteroom.

There were some fifteen Aboriginal groups living in the Darling River area on the western plains of New South Wales. The main group at Broken Hill was the Wiljakali1. Their territory was expansive because of the dry drought prone environment. The Wiljakali lived a traditional lifestyle into the 1870s, but by the 1880s their way of life was changing with many Aboriginal people getting work on sheep stations and in mining. With the failure of most of the sheep stations during the severe 1890s drought, many local Aboriginal groups ended up living in reservations or missions created under the Aborigines’ Protection Act of 1909. The twentieth century federal government policy of removing Aboriginal children from their families had a significant impact upon Aboriginal communities in the area.

Broken Hill was named by the British Explorer Charles Sturt during his search for an inland sea in 1844. Western plains towns far away from the Darling River, such as Broken Hill, exist because of mining after 1875, when huge deposits of gold, silver, copper and opal were found.

The township of Broken Hill was developed in the ‘Broken Hill Paddock’ on the Mt Gipps Station. In 1883 that three Station workers pegged the first mineral lease on this property. A township was soon surveyed in 1883 and Broken Hill was initially known as a shanty town with an entire suburb named ‘Canvas Town’ for its temporary buildings.

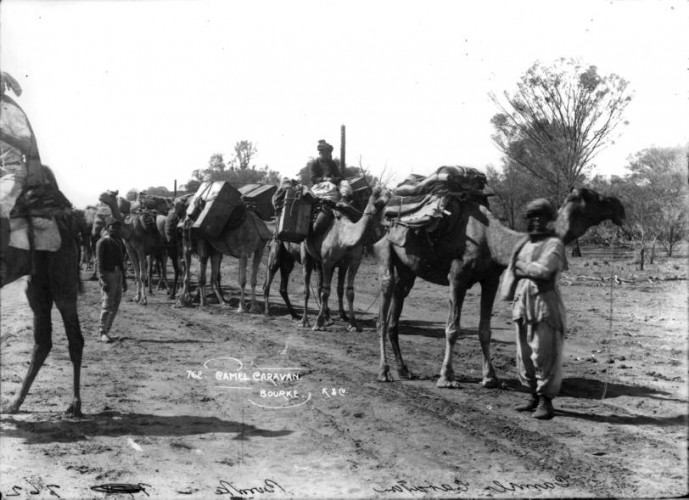

As European settlement moved further west beyond Bourke it became clear that horses would not provide a sustainable mode of transport.

The solution was to import camels. Afghan cameleers were recruited to Australia to handle the camels. The introduction of camels and Afghan cameleers proved to be a turning point in the exploration and development of the Australian interior.

The most successful of all the Afghan cameleers was Abdul Wade. Wade arrived in Australia in 1879 and initially worked for Faiz and Tagh Mahomet in South Australia. In 1893, Wade moved to Bourke and began importing camels and recruiting Afghan cameleers for the recently formed Bourke Camel Carrying Co. Dost Mahomet was a prominent Afghan camel driver who worked at Broken Hill. His grave lies three kilometres from Menindee, on the road to Broken Hill. He is thought to be the first Islamic person to be buried on Australian soil.

Cameleers led hundreds of camel trains throughout inland Australia in the nineteenth century and by the turn of the twentieth century their camel trains provided transport for almost every major inland development project. The cameleers laboured across the continent, carting produce, water, mail and equipment at a time when roads and railways were not constructed. The hardy camels and their drivers were crucial to the success of important projects such as the construction of the Overland Telegraph. The early Cameleers contributed greatly to the development of rural and remote Australia.

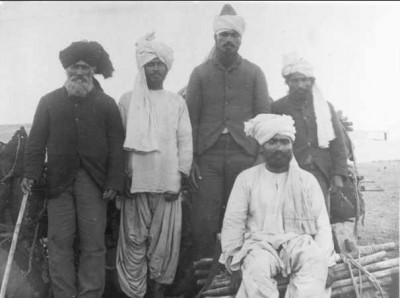

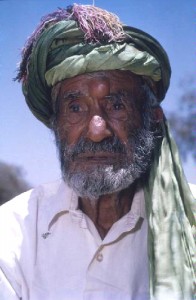

Over 20,000 camels were brought to Australia from 1850 to 1900 from different parts of the world. The cameleers came from different countries such as Kashmir, Rajastan, Egypt, Persia, Turkey, Punjab, Baluchistan, Afghanistan, India and Pakistan. They were known as ‘Afghans’, although very few were actually from Afghanistan.

Camels at Broken Hill were imported Sir Thomas Elder in 1866 for work in northern South Australia. The ‘ Ghans’ as they became known, were working the area before Broken Hill’s establishment in 1883 and the Afghan camel teams were a familiar sight in the far west of New South Wales. Camels were used to haul wool on ten ton drays travelling at a rate at 15 miles per day. When they struck camp the Afghans slept in a temporary corrugated-iron shed or humpy of tree branches. They led a nomadic life with few personal possessions. They were followers of Islamic who did not drink alcohol. Because of their sobriety they were favoured as reliable workers and carting alcohol to the outback hotels.

Early Camel dray. Photograph by Patricia Assad. Courtesy Heritage Branch, New South Wales Department of Planning

Detail of the camel dray interpretation. Photograph by Patricia Assad. Courtesy Heritage Branch, New South Wales Department of Planning

Afghan camel teams played a crucial role in exploratory expeditions and scientific survey parties into the outback. Afghans were among the first non-Aboriginal people to sight Uluru and the Karlu Karlu. They had their own names given to places such as Allanah’s Hill and Kamran’s.

The Afghans travelled lightly and were always ready to move. Like the Chinese Station workers the Afghans were on short term work contracts that did not allow their wives or children to travel with them to Australia. Many men worked and lived communally observing strict religious practices that discouraged extensive interaction with the European workers and outback towns. As a result the Afghans generally lived away from Europeans in makeshift camel camps and later developed ‘Ghantowns’ on the edges of stations and towns.

Mostly they were solitary travellers deprived of the sense of community or ‘Ummah’ of Islamic culture. The Afghans performed their prayers five times daily wherever they where. In Islam great emphasis is placed on the conduct of prayer (Salat) as a way of connecting the individual with their deity. Salat can be performed at any clean place ensuring that the worshipper is directed towards the Kaaba in Mecca. Muslims are encouraged to perform their obligatory Friday prayers and celebrate key events in the Islamic calendar at a mosque in congregation2.

A mosque, which is referred to in Arabic as a ‘Masjid,’ is a place to lay flat and pray on prayer mats. It is a place to gather for daily prayers and festivals and religious education. A mosque can also be a place for other community activities and carrying out community welfare services.

Footwear must not be worn by any person entering the mosque and the Afghans observed the custom of having their feet washed before entering the building. After removing their shoes the Afghans stood beside a concrete channel as water was poured over their feet. They then entered the mosque by walking on two specially constructed stepping stones on to mats in side the building.

An important celebration of the Islamic religion is Eid ul-Fitr the marking the end of Ramadan (the month of fasting from sunrise to sunset), and Eid ul-Adha, (the Sacrifice of Feast). According to Islam, fasting should not be undertaken while travelling, so the Afghans would stop work during the Holy month and join together to fast and pray at the mosque. At the end of the 30 days of fasting the Afghans would enjoy the Eid-ul-Fitr feasting celebration3.

Prayer Mats inside the Mosque. Photograph by Patricia Assad. Courtesy Heritage Branch, New South Wales Department of Planning

The first mosque in New South Wales was built in Broken Hill in 1887. This was some 16 years after the first mosque to be built in Australia was constructed in Maree in northern South Australia in 1861.

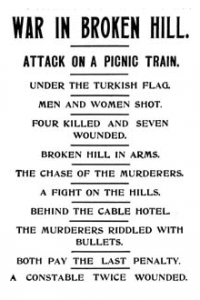

On the 1st of January 1915. Two men shot dead four people and wounded seven more, before being killed by police and military officers. While the attack was politically inspired, as declared by the perpetrators in notes, the men were not members of any sanctioned armed force. Since, at that time, Australia was preparing to attack the Ottoman Empire, they were first speculated to be Turkish, but were later identified as being Muslims from an area of the British colony of India that is now modern day Pakistan.

The attackers were both former cameleers working at Broken Hill. They were Badsha Mohammed Gool, an ice-cream vendor and Mullah Abdullah, a local imam and halal butcher.

Following World War One camel transport was finally over taken by rails and road and the Afghan cameleers vanished. Some returned to Afghanistan or resettled in the new Islamic state of Pakistan. Most Afghans who came to Australia were single or if married left their wives behind as they expected to return wealthy. Many remained single, others married Aboriginal women and few married European women. By the 1920s the ‘ghantowns’ had been abandoned and the camels set loose to roam feral in the outback.

The Broken Hill Mosque collection is historically significant as evidence of early cameleering, the history of Broken Hill and of the historic presence of Islamic culture in Australia. It is evidence of the contribution the ‘Afghans’ made to opening up the outback and the in construction of the overland telegraph lines. The mosque has historical significance as the first mosque built in New South Wales and the only surviving mosque built by cameleers in Australia.

The Broken Hill Mosque is rare being the first mosque built in New South Wales and the only surviving Ghantown mosque in Australia.

The Broken Hill Mosque collection has social significance for the Australian Islamic Community for its association with the men who built the mosque, who came from different parts of the Middle East. These men made a vital contribution by significantly opening up the outback, constructing overland telegraph lines which connected New South Wales to London, constructing railways, erecting fences, acting as guides for several major expeditions, as well as supplying almost every inland mine or station with its goods and services

The Broken Hill Mosque and its collection has aesthetic significance for its blending of traditional Islamic design and motifs with the use of local corrugated iron sheets and other vernacular materials, such as various woods. The mosque represents Islamic architectural style and detailing such as the arch in the alcove, and the wudu facilities. It provides evidence in built form of a Middle Eastern and Islamic cultural aesthetic in Australia.

The Broken Hill Mosque collection has research value role as a rare source of information which offers material evidence of this poorly documented aspect of early Australian outback settlement and history.

The Broken Hill Mosque and its collection has interpretive significance as an example of a typical ‘Ghan town’ mosque used with distinctive local elements, such as the corrugated iron, which is representative of the pioneering days in the far west of New South Wales. It represents a community approach to survival and adaptation to life in a foreign country.

Footnotes

2 NSW Heritage Office, Department of Planning. www.heritage.nsw.gov.au/07_subnav_01_2.cfm?itemid=5051563

3 Ibid.

Bibliography

Coupe, S & Andrews, M 1992, Was it only Yesterday? Australia in the Twentieth Century World, Longman Cheshire, Sydney.

Heritage Office & Dept of Urban Affairs & Planning 1996, Regional Histories of NSW, Sydney.

Heritage Collections Council 2001, Significance: A guide to assessing the significance of cultural heritage objects and collections, Canberra.

Websites

http://hosting.collectionsaustralia.net/stories/turks/index.html

www.visitbrokenhill.com.au/accom_result1/railway-mineral-train-museum/

Migration Heritage Centre

August 2010 – updated 2011Crown copyright 2010©

The Migration Heritage Centre at the Powerhouse Museum is a NSW Government initiative supported by the Community Relations Commission.

www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au

Regional Services at the Powerhouse Museum is supported by Movable Heritage, NSW funding from the NSW Ministry for the Arts.