Era: 1840 - 1900 Cultural background: Chinese, English Collection: Powerhouse Museum Theme:Gold Government Labour Movement Miners Riots Settlement

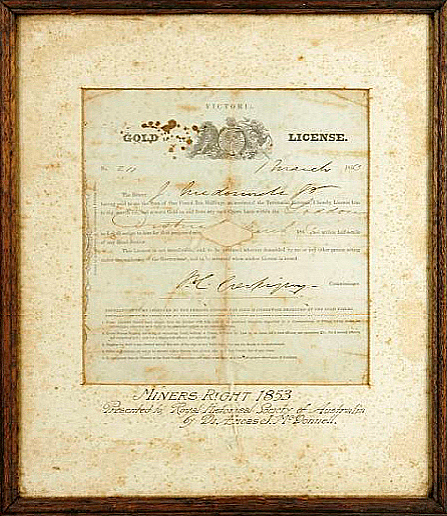

Licence for gold mining, 1853. Courtesy of the Powerhouse Museum

Collection

Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, Australia.

Object Name

Gold Mining Licence.

Object/Collection Description

Licence for gold mining, framed, paper / wood / glass, issued to J McDonnell, printed by John Ferres, Government Printing Office, Victoria, Australia, 1853. At centre top is the Victorian coat of arms with inscription: ‘VICTORIA / GOLD LICENCE’. The name of the licence owner and place and date of its issue are written in ink and the licence is signed in ink by the Commissioner. The licence also details the conditions under which it is issued. Licence issued to J McDonnell to mine at Loddon. The licence is window mounted under cardboard which is inscribed in black ink ‘MINERS RIGHT 1853 / Presented to, Royal Historical Society of Australia / by Dr. Aeneas J. McDonnell.’. The whole is framed with a dark brown wood frame and under a sheet of glass. The back is covered with brown paper inscribed with blue pencil ’209′. Dimensions: 330mm high X 290mm wide X 13mm deep.

In March 1851, Edward Hargraves wrote to the Sydney Morning Herald to announce that he had found payable gold just outside the New South Wales town of Bathurst. By 15 May over 300 diggers were in the area prospecting for gold and the Australian gold rush had begun. The following month further discoveries were made at Clunes in Victoria and later Warrandyte, Bunninyong and Ballarat. By the end of the year half the adult male population of the colony was at the diggings.

Lambing Flat miners’ camp, c.1860s Courtesy State Library of New South Wales

With so many people leaving for the gold fields, many businesses found it hard to keep operating. Ship crews deserted, leaving vessels stranded in port, shepherds left their flocks, government officials, clerks, teachers and policemen left their jobs in the excitement. Soon they were joined by thousands of immigrants from Europe, America, China and New Zealand keen to try their luck. Between 1852 and 1861 over 342,000 people arrived, often enduring appalling conditions on overcrowded ships. Conditions were not much better on land as tent cities sprang up to accommodate the burgeoning population and the cost of food and necessities sky rocketed.

Although there were some remarkable discoveries on the gold fields, few people made their fortune and most drifted back to towns and cities looking for work. Some of the immigrants returned to their countries of origin but the majority stayed. Australia’s first gold rush transformed the colonies. Convict transportation to the eastern colonies ceased, the population more than doubled, and agriculture expanded and new industries were established.

Both the New South Wales and Victorian governments didn’t quite know how to react to this huge influx of people into regional areas. The rush brought sudden labour shortages to NSW and then to Victoria. People even dared to leave their employment for the gold fields without permission. People needed to be pushed back to their near servile positions. The owners of pastoral runs and retail businesses saw the problem as a threat to their control and self interest and not as a government providing services issue.

Both New South Wales and the Victorian governments sought to regulate where people went and to how to manage the infrastructure like roads and bridges required to accommodate large numbers of people on the move. Pastoralists wanted infrastructure to service their businesses while diggers complained about the lack of services on the gold fields. Police were needed to maintain law and order and escorts engaged to guard gold bullion from bushrangers. All of this costs money. Colonial politicians were reluctant to raise taxes that would effectively would impact on their own businesses and the wider middle class population. Both the New South Wales and Victorian governments decided to the best way of to control miners and to raise money to provide infrastructure was to introduce a 30s. Miners Licence. Thirty shillings was a lot of money at that time and many diggers found it difficult to raise the fee. Added to this, most of the easy alluvial gold had started to run out and big companies were moving in establishing deep hard rock mines that put the small alluvial miners out of business.

Roll Up banner, 1861, Courtesy Wikimedia

In the face of these hardships the Chinese were often scapegoated by disgruntled European miners as seen in the violent anti -Chinese riots at Turon (1853), Meroo (1854) Rocky River (1856) Tambaroora (1858) Lambing Flat, Kiandra and Nundle (1860 and 1861) and Tingha tin fields (1870). They were seen initially as oddities, later as rivals and then as threats to white Australia.

The gold licence system caused considerable unrest on the diggings. It was regarded as a tax and greatly resented since it was applied regardless of the success or failure of the digger. However, the gold commissioners and Police known as ‘traps’ enthusiastically policed the gold fields, checking on licences and arresting and fining the unfortunate diggers who could not produce them.

The Police ‘licence hunts’ were often brutal, corrupt, unfair and inefficient. These licence hunts came to symbolise the government’s oppression of the diggers and directly led to major protests on gold fields in Sofala in 1852, Bendigo in 1853 and the Eureka Rebellion in 1854. A year after the Eureka Rebellion the gold licence was replaced by a Miner’s Right which cost one pound a year for the right to dig and also entitled the owner to vote in parliamentary elections. Peter Lalor, the miner’s leader at Eureka was elected to the Victorian parliament.

The gold licence historic significance lies in its relationship to the themes of the gold rush experience, the beginning of mass migration to Australia, colonial democracy, the migration of British trade unionism and the development of racially discriminative Colonial policies culminating in the first act of the newly Federated Commonwealth of Australia, the 1901 Immigration Restriction Act.

The gold licence has aesthetic significance in the design, language and the style of a 19th century colonial document the Victorian Coats of Arms and the Commissioners signature.

The gold licence provides a research tool for historians to explore the culture and politics of the Australian gold fields. The licence is evidence of the unrest on the gold fields and the importation of ideas of democracy and emancipation with the migrant miners.

Objects from the gold rushes have an intangible significance to many regional and urban communities as it is a major theme in Australian history and many communities can trace their family history to the gold rushes.

The gold licence is well provenanced. This licence was issued to J. McDonnell in March 1853. At the time he was working on the Loddon gold fields on the Loddon River in western central Victoria. The gold licence was donated to the Royal Australian Historical Society by a descendant of J. McDonnell, Dr Aeneas J. McDonnell.

The gold licence is rare because it was made for a specific purpose and one of a few licences that remain from that time.

The gold licence represents the experience of the 19th diggers on the gold fields, colonial government’s attitudes to the economy and democracy and the evolution of the myths surrounding the Chinese created largely on the gold fields that provided the seeds for the ideology that created the 1901 Immigration Restriction Acts.

The condition of the object is good given the rarity and fragile nature of the fabric. There is evidence of some foxing, fading and tears around the edges.

The gold licence is a powerful interpretive tool in communicating the experience and the treatment of the European and Chinese miners on the diggings.

Bibliography

Heritage Office & Dept of Urban Affairs & Planning 1996, Regional Histories of NSW, Sydney.

Heritage Collections Council 2001, Significance: A guide to assessing the significance of cultural heritage objects and collections, Canberra.

Wilton, J 2004, Golden Threads: The Chinese in Regional NSW, 1850 – 1950, New England Regional Museum & Powerhouse Publishing.

Websites

Migration Heritage Centre

June 2007 – updated 2011

Crown copyright 2007©

The Migration Heritage Centre at the Powerhouse Museum is a NSW Government initiative supported by the Community Relations Commission.

www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au

Regional Services at the Powerhouse Museum is supported by Movable Heritage, NSW funding from the NSW Ministry for the Arts.