Era: 1790 - 1830 Cultural background: English Collection: Sydney City Council Theme:Agriculture Archaeology Convicts Settlement

Collection

Sydney City Council Archives, Sydney, Australia.

Object Name

Old Sydney BuUrial Ground Headstone.

Object description

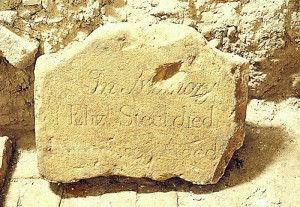

Georgian headstone made of Sydney sandstone. Remnants of an inscription visible: In Memory of, Eliz Steel died, 1795 Aged …Dimensions: Approximately 345mm high x 480mm wide x 200mm deep.

When England lost its American colonies in 1778 in the American War of Independence, it began to look to the Pacific to replace these markets and resources. Joseph Banks, an influential naturalist and merchant, convinced the British government that breadfruit from Tahiti was an ideal crop to grow in the West Indies and use to feed slaves. Banks also argued that Botany Bay in New South Wales would make an ideal British port in the Pacific and that a settlement should be established with indentured convict labour. A penal settlement was also seen as a possible solution to the increasing problem of petty crime and a growing prison population in English cities.

These problems were compounded by massive unemployment due to the ‘Industrial Revolution’. Food and materials once supplied from farms across the British Isles were now replaced by imports that were processed in mills and factories. British farm owners turned their land over to sheep grazing. They evicted farm labourers and their families, who, with no jobs and nowhere to live, flocked to the cities looking for work in the mills. Many resorted to petty crime to feed their families and indeed petty crime became a way of life for a whole underclass. Criminality was widespread because it was hard to catch criminals in the warren like streets of the industrial cities and there was not a dedicated professional Police Force. Despite this the few gaols started to fill up and a solution to the crime problem was sought.

Despite it being a huge and very expensive experiment to set up a colony in an unknown land on the other side of the world, Britain decided to establish a penal colony at Botany Bay under the leadership of Captain Arthur Phillip. This was hoped to replace the convict dumping ground lost in North America, clear out the British Gaols, provide a deterrent to crime in Britain and establish a deep water port in the South Pacific for Britain to expand its territories.

The First Fleet of 11 ships, each one no larger than a Manly ferry, left Portsmouth in 1787 with more than 1480 men, women and children on board. Although most were British, there were also Jewish, African, American and French convicts. After a voyage of three months the First Fleet arrived at Botany Bay on 24 January 1788. Here the Aboriginal people, who had lived in relative isolation for 40,000 years, met the British in an uneasy stand off at what is now known as Frenchmans Beach at La Perouse. On 26 January two French frigates of the Lapérouse expedition sailed into Botany Bay as the British were relocating to Sydney Cove in Port Jackson. The isolation of the Aboriginal people in Australia had finished. European Australia was established in a simple ceremony at Sydney Cove on 26January 1788.

Between 1789 and 1791, the settlers at Sydney Cove were critically short of food. To make matters worse, the supply ship Guardian was wrecked off South Africa before it reached the Colony, and HMS Sirius, one of two of the Colony’s Navy vessels, was wrecked on Norfolk Island en route to China seeking food. In desperation, the HMS Supply, the Colony’s second Navy ship, was sent to Indonesia for food. Hopes were raised when a vessel arrived in Port Jackson in 1790, but it was not the Supply, but the Second Fleet of five ships carrying over 730 people.

This Second Fleet was a disaster, with its human cargo severely abused and exploited by the private ship owners. Of 1000 convicts on board, 267 died and 480 were sick from scurvy, dysentery and fever. The supplies on board the Second Fleet were supposed to feed the convicts, but the ship owners withheld the supplies for sale until after the convicts disembarked. Phillip, enraged by this behaviour as he had to further ration existing supplies, became desperate to establish farms and a local economy.

Farms, established with convict labour at Rose Hill (Parramatta) and later at Richmond and Windsor, were soon producing crops. Explorers set out to find new land and areas were opened up in the Liverpool area for market gardens, viticulture and sheep grazing for wool. These farms and pasture all depended on an abundant source of free convict labour to survive. Convicts were assigned to farmers under strict conditions known as the Assignment System.

The mortality rate in the colony was high. Many convicts carried chronic disease and ailments that led to an early death. Epidemics of small pox, cholera and whooping cough swept through the colony regularly imported by the convict transports, cargo and migrant ships that berthed at Darling Harbour and the Rocks.

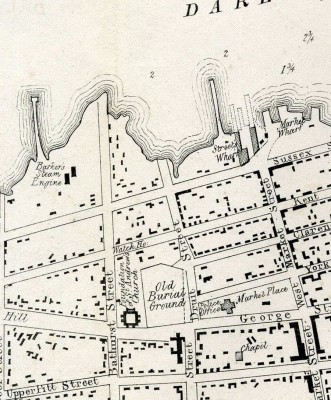

By 1793 the principal burial ground for the colony was on the site where the Sydney Town Hall now stands, on the corner of George and Druitt streets. This cemetery is commonly called the Old Sydney Burial Ground, but it is also known as the George Street Burial Ground, the Cathedral Close Cemetery, and the Town Hall Cemetery.

David Collins recorded in his journal in September 1792 that the site was chosen by Governor Phillip and the Rev. Richard Johnson. In accordance with the latest philosophies on the disposal of the dead, the burial ground was located on the outskirts of the town; so that it would not affect the health of the population.

In 1812 Governor Macquarie authorised the extension the burial ground to the north and west, and granted a site for a new church St Andrew’s in George Street, beside the cemetery. With the extension, the burial ground covered just over 2 acres.

Detail from Plan of Sydney & Pyrmont, 1836. Photograph Stephen Thompson. This map shows the size and boundaries of the Old Sydney Burial Ground. The building within the cemetery grounds is the wooden temporary St Andrews Church.

The Old Burial Ground served Sydney for 27 years. Its management was ad hoc and it was not formally gazetted as a burial ground and it was apparently not consecrated. No formal cemetery register or plan of the burials was kept. The parish register of St Phillip’s recorded many of the burials, but in between clergy appointments it was poorly maintained. The Rev. William Cowper later estimated in 1845 that there were about 2000 burials in the old burial ground. The inadequacies of parish records were not addressed until 1856, when official civil registration of deaths was introduced.

The cemetery buried both the convict and free population. There were no apparent denominational sections, but some social distinctions were maintained in the organisation of the cemetery. Early Sydney residents recalled that the military were buried in certain parts of the cemetery. The corner close to Kent Street hosted graves of the non-commissioned officers of the 46th and 48th Regiment. Over in the south-west corner near the Presbyterian Church, soldiers of the 73rd Regiment were buried. And in the ground fronting George Street, near Druitt Street, were buried some non-commissioned officers of the New South Wales Corps.

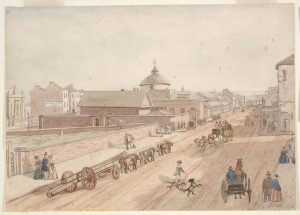

George Street looking north showing… the old Burial Ground…, John Rea, c.1840s. Courtesy State Library of New South Wales

By 1820 the cemetery was full, and its clay soil and poor burial practices rendered it ‘offensive to the inhabitants of the neighbourhood’. The governor declared the cemetery closed and a new burial ground was at the Devonshire Street cemetery now the site of Central Station. Some vaults and graves were opened and the corpses and sepulchre deposited in the new burial ground.

Once closed, the cemetery was neglected. By 1837 many of the headstones had been vandalised. The cemetery became ‘a resort for bad characters at night’ and stray animals during the day. Pigs, goats and horses wandered amongst the graves, many of which lay open exposing brick vaults and timber coffins. Stones were broken, defaced and trodden over.

Odour was arising from the old burial ground that became unbearable in hot weather. Many blamed clandestine burials and grave robbers opening graves to steal leaden coffins. But there were other explanations for the offensive smells. It was reported people used the Old Burial Ground as a toilet ‘with a most revolting and disgusting disregard of decency’.

The remains from the Old Sydney Burial Ground were removed by the Council to the new Necropolis at Haslem’s Creek in 1869. However the headstones were not relocated. It was too difficult and time consuming to match headstones to remains in the overgrown cemetery and the Council was keen to get the town hall building works underway. Instead they erected a new imposing Classical styled sandstone monument at Rookwood. The inscription records the name of the Mayor but does not list any names of those buried in the old cemetery!

In 1991, Sydney Town Hall underwent major restoration works. During excavations to lay new stormwater pipes under the Lower Town Hall, workmen discovered evidence of burials. Archaeologists were employed to excavate the site and record their findings.

Overlying the lid of one of the graves discovered in 1991 was the upper portion of a Georgian headstone, made of Sydney sandstone. Remnants of an inscription were visible:

In Memory of

Eliz Steel died

1795 Aged …

Elizabeth Steel arrived in Sydney Cove as a convict on board the Lady Juliana on the 3rd June 1790, as part of the Second Fleet, aged 23 or 24. At the time of her sentencing authorities described her as being ‘mute by visitation of God’, which is the earliest record of a deaf Australian, but there is no historical evidence that she used a sign language. Her charge at the Old Bailey was for stealing a silver watch from George Childs, who was a customer at the public house she worked at as a prostitute. After two months in Sydney, Elizabeth Steel was transferred to Norfolk Island. In November 1791, Steel married a fellow convict, Irish born James Mackey. Together they successfully farmed a 10-acre farm until the end of their sentences. Elizabeth returned to Sydney in 1794, but died the following year aged 29. Her burial at the Old Sydney Burial Ground was recorded on 8 June 1795.

Although this headstone was found above the remains of the vault containing the skeletal remains of a woman, forensic tests confirmed that there was no relationship between them. It is thought that the headstone may have fallen from another grave, possibly during the construction of the Town Hall in the late 1860s.

In 2003 more graves were discovered to the north of the Town Hall. Excavations were required in conjunction with alterations to the building. When the paving was removed between the Town Hall and Druitt Street, evidence of the old ground surface was found immediately below. Several graves were uncovered, including some brick vaults. The graves are aligned in an east-west direction as are all other graves discovered previously on the site. The discovery of these graves relatively undisturbed so close to the Town Hall suggests that in 1868-69 the Council simply cleared the site of headstones and only removed graves when they got in the way of construction.

There are a number of smaller grave cuts, indicating the graves of infants. This photograph shows the excavation of a grave of an adult and infant buried together. Bone fragments have confirmed this was the grave of a woman; she probably died during childbirth. Courtesy City of Sydney Archives.

The headstone has historical significance as a rare object from the convict era. The headstone is a direct link to a female convict who was deaf and reveals the Colonial Government’s attitude to and treatment of convicts as indentured labourers in a strict social structure designed to provide cheap labour to build an expanding British global empire.

The headstone is significant for researchers as it is one of the few existing objects from the Old Burial Ground.

The headstone has intangible significance as a relic from Australia’s brutal convict origins and early settlement.

The headstone is well provenanced and documented from the archaeological study on the Old Burial Ground site at the Sydney Town Hall.

The headstone is extremely rare. It is one of a few existing headstones from the Old Burial Ground site that is linked to an identifiable person, Elizabeth Steel.

The object represents a time early in Australia’s history when the colony was still establishing itself and exploring its new environment. The headstone also represents the coming of Europeans to Aboriginal Australia as it is instantly recognisable as a European object of mourning, documenting the death of a person, a symbol of the British penal colony, and expansion from Sydney Cove. The headstone is in fair condition for its age and material.

The headstone has interpretive significance for telling the story of a particular person who faced many challenges and hardships and the dependence of convict labour in the establishment, survival and expansion of the early colony at New South Wales. It also interprets the brutal convict origins of European Australia and the Government system.

Bibliography

Coupe, S 1992, & Andrews M. Their Ghosts may be heard: Australia to 1900, Longman Cheshire, Sydney.

Fowell, N 1988, The complete letters of Newton Fowell 1786-1790, midshipman and lieutenant aboard the Sirius flagship of the first fleet on its voyage to New South Wales, edited with commentary by Nance Irvine. Sydney.

Hughes, R 1987, Fatal Shore, London.

Heritage Collections Council 2001, Significance: A guide to assessing the significance of cultural heritage objects and collections, Canberra.

Tench, W 1979, Sydney’s first four years: being a reprint of A narrative of the expedition to Botany Bay and, A complete account of the settlement at Port Jackson, Sydney.

Websites

http://www.hht.net.au/museums/hpbm/hyde_park_barracks_museum

http://www.convicttrail.org/about.php?id=a4b7

Migration Heritage Centre

May 2010 – updated 2011

Crown copyright 2010©

The Migration Heritage Centre at the Powerhouse Museum is a NSW Government initiative supported by the Community Relations Commission.

www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au

Regional Services at the Powerhouse Museum is supported by Movable Heritage, NSW funding from the NSW Ministry for the Arts.