Era: 1790 - 1830 Collection: Mitchell Library, State Library NSW Theme:Convicts Exploration Government Macquarie Military Settlement

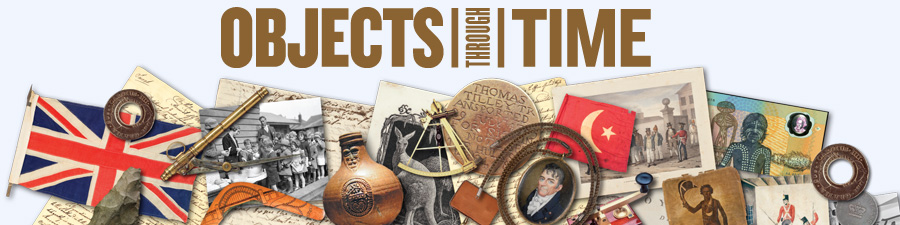

Lachlan and Elizabeth Macquarie miniature portraits, 1810. Courtesy State Library of New South Wales

Collection

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

Object Name

Lachlan and Elizabeth Macquarie Miniature Portraits.

Object/Collection Description

Watercolours of Gov Lachlan and Elizabeth Macquarie on an ivory miniature c.1810. Rectangular black wooden frame with oval shaped glass and painted gold edge in centre, backed in black “American” paper, and a triangular metal loop with black ribbon attached to centre top of frame for hanging. Macquarie in this portrait wears a dress uniform that comprises a military jacket of red face cloth and a blue-black stand collar, gold epaulettes, and regimental brass buttons. Elizabeth Macquarie in this portrait wears an Elizabethan revival style dress with a ruff collar made of fine white cotton that is tucked into the back of the black coloured dress, gold braid trim or armbands at the base of puffed sleeves, and a mourning brooch at neckline. Dimensions: 161mm high x 141mm wide.

Lachlan Macquarie was born at Ulva, one of the Hebrides Islands, on 31 January 1761. At an early age he was sent to Edinburgh to be educated at the high school. On 9 April 1777 he entered the army as an ensign in the 84th regiment of foot, and he served the military in numerous countries and rose through the ranks until 1805 when he was sent to India to take command of the 86th regiment and was appointed Military Secretary. In 1807 he returned to England and was married to his second wife, Elizabeth Henrietta Campbell. In the following year, when the news of the deposition of William Bligh, Governor New South Wales, reached England, it was decided that a new Governor should be appointed and the position was offered to Brigadier-general Nightingall. It was also decided to send the 73rd regiment with Macquarie in command to relieve the corrupt New South Wales Corps. Nightingall was quite sick and was unable to go, and on 8 May 1809 Macquarie was appointed Captain-General and Governor-in-Chief of New South Wales.

Macquarie sailed on 22 May and made his official landing at Sydney on 31 December 1809. He had orders to reinstate Bligh for one day but this could not be done as Bligh was at Hobart. He was in some doubt as to how he would be received, but he had brought the 73rd regiment with him and there was no trouble. The officers of the New South Wales Corps soon realized that their reign was at an end, though for about 18 years they had dominated the Colony through corruption and subversion. Despite the efforts of three previous Governors to control their traffic in spirits and land they had become very wealthy and influential.

Macquarie was shocked at what found in New South Wales. He found the country was “threatened with famine; distracted by faction; the public buildings in a state of dilapidation; the few roads and bridges almost impassable; the population in general depressed by poverty…, the morals of the great mass of the population in the lowest state of debasement, and religious worship almost entirely neglected”.

Macquarie immediately got to work and dismissed all officials who had been appointed by the New South Wales Corps, and restored the people who had been in those jobs before the Rum Rebellion. One of his first actions was to reduce the number of licensed public houses in Sydney from 75 to 20, though very soon after their number was much increased, and he began the widespread building program that characterised his administration. The streets were straightened and improved, new barracks were built for his regiment, and the New South Wales Corps was sent back to England. In November he began a tour of the colony and in little more than a month was able to form some opinion of its capabilities.

Unfortunately most of the good land on the Hawkesbury/ Nepean Rivers near Sydney was subject to flooding and a passage through the mountains had not yet been found. Macquarie set to dismantling existing monopolies in the Colony, and succeeded in preventing the starvation and inflation of prices by importing grain from India keeping it in the Government Store until required.

His one early mistake was to give him much trouble. He was anxious that emancipated convicts should have every opportunity to rehabilitate themselves, and he invited some of them to his table and even appointed them as magistrates. This policy was widely unpopular with the wealthy ‘exclusives’ landowners and was ultimately unsuccessful. This policy only went on to cause him further problems and the class faction ridden colony.

Macquarie understood the role of providing education to the betterment of society, and free schools for boys were opened at Sydney and Parramatta within a few months of his arrival. Protestant evangelical churches and the Sunday school movement was promoted to raise the religious and moral tone and to counter the incursion of Catholicism in the colony.

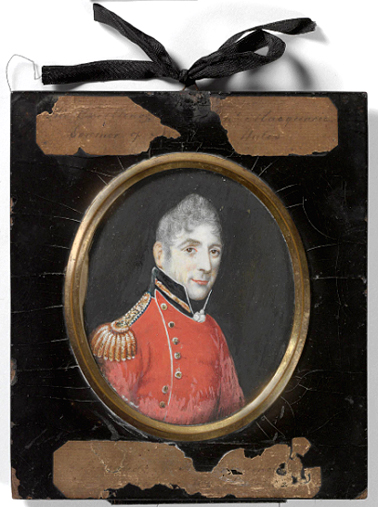

Obelisk of distances 1818, Macquarie Place, Sydney, c.2011. Photograph Stephen Thompson

The first post-office was opened on the 23rd June, a large market place was proclaimed on 20 October 1810, and attempts were made to keep the Tank stream that ran through central Sydney pure. In the same month Macquarie was able to report to the Earl of Liverpool that a turnpike road with a number of bridges was being constructed from Sydney to Hawkesbury, a distance of nearly 40 miles. He also pressed for the closure of Norfolk Island as a place of secondary punishment, stating that it could never “be of the least advantage or benefit to the British government or to this colony”. In 1811 Macquarie successfully reorganized the police of Sydney and made new regulations for the management of the market. He suggested to the Earl of Liverpool that trial by jury should be established, and that various officials of the court should be sent out from England. He was then on very good terms with the Judge- Advocate Ellis Bent and recommended that he should be made a judge.

The British Government was already questioning the increase in the New South Wales expenditure, and in November 1812 Macquarie stated that a great proportion of the expenses incurred in the first 18 months of his government were to rebuild and install essential services and buildings which were not likely to occur again.

In 1813 a way was found through the Blue Mountains by Blaxland, Wentworth and Lawson. It is possible that the importance of this feat was not fully realised at the time; for there appears to have been no public recognition of it. On the 19th November 1813, Macquarie sent G.W. Evans to explore beyond the mountains. In January 1814 he was able to report to Bathurst that Evans had discovered “a beautiful and champaign country of very considerable extent and great fertility” which… will at no distant period prove a source of infinite benefit to this colony”.

The southern wing of the Rum Hospital, c.2011. Photograph Stephen Thompson

He has also been criticised for his building of Sydney (Rum) Hospital by giving the contractors a monopoly for three years of the importation of rum. A hospital, however, was badly needed and it was no easy problem to find the funds to build it. In a few years the local revenue and port dues enabled Macquarie to enter on an immense programme of public works, which included hundreds of miles of roads and several military barracks and country hospitals, new barracks for the convicts in various centres, and churches in Sydney and country towns. In this work he had the assistance of ex-convict Francis Greenway. Greenway was unfortunate that he was not able to go on with his proposed plans of Sydney. Macquarie did succeed in endowing Sydney with the Botanical Gardens, the Domain, Hyde Park and the Sydney University grounds.

In 1815 Macquarie fell out with both the Judge-Advocate Ellis Bent and Judge Jeffery Bent over the emancipist issue. Macquarie undoubtedly was too proud to give in, but quite justified in his contention that convicted men who had served their sentence should be entitled to the rights and privileges of free British subjects. Whether this should be extended to allowing a man “guilty of a crime of an infamous nature” who had consequently lost his professional standing to appear as Attorney in the Court was a question that most professional people in the Colony found difficult. Macquarie also quarrelled with the Rev Samuel Marsden on a similar matter. He had appointed two ex-convicts, Andrew Thompson and Simeon Lord, as magistrates, and Marsden objected to being associated with them and resigned his magistracy. Macquarie then announced that he “had been pleased to dispense with the services of the Rev Samuel Marsden as justice of the peace and magistrate” which infuriated Marsden more. The issue here was that critical accounts of Macquarie’s performance as Governor had been sent to the Colonial Office in Britain, and Macquarie thought that Marsden was responsible.

Macquarie in 1815 had court-martialled an Assistant Chaplain, Benjamin Vale. He complained to the Colonial Office and was severely rebuked and reminded that chaplains could be court-martialled only for offences involving their character. Macquarie in his reply of 1 December 1817 had suggested that he should resign, Earl Bathurst in his letter in reply of 18 October 1818 tactfully told Macquarie that though it was impossible for him to resign pointing out “those cases in which you have either transgressed the laws or adopted an erroneous line of conduct”, there had never been any imputation upon Macquarie’s character or the uprightness of his intentions. He had therefore deferred submitting his resignation to the Prince Regent until Macquarie had had an opportunity of reconsidering it. This letter never reached Macquarie and meanwhile various complaints against him had found their way to Lord Bathurst. Increasingly Macquarie saw himself acting for the betterment of society and those who opposed him being motivated by self interest and self promotion.

The Colonial Office decided to appoint John Thomas Bigge, a very experienced barrister, as a commissioner to proceed to New South Wales to undertake an inquiry and produce a Report on the situation. In a dispatch dated 30 January 1819 Macquarie was informed of this and copies of Bigge’s instructions were sent to him. The scope of the inquiry was to report on all the operations of the Colony. Macquarie was directed to assist Bigge in every way. Unfortunately Bigge did not appreciate Macquarie’s main desire that convicts should be allowed to redeem themselves, and generally he was not over appreciative of the all of the good work done by Macquarie. Macquarie resigned his office as Governor of the colony on the 29th February 1820. On 1st December 1821 he handed the Governorship over to his successor Sir Thomas Brisbane, and in February 1822 left for England. He died at London on 1st July 1824 and was buried on the island of Mull. He was survived by his wife and one son, who died unmarried.

Macquarie was a tall, energetic man. He had been a well respected officer and administrator in the army, and came to his new office with practically the powers of a dictator. Macquarie was inclined to stand on his pride and not to compromise where his powers were concerned. Macquarie’s reforms and restructure of the Colony came just at the right time. There had been a slight improvement in the conditions under each of the preceding Governors, and reform of the Colony was need if it was not to face extinction as another abandoned penal experiment. It was unfortunate for Macquarie that he came into conflict with Marsden, Jeffery Bent, and Bigge, who could all be just as stubborn or difficult, but his answer to all criticism is the work he did, and the general improvement that followed in the situation of the Colonists.

Hyde Park Barracks, c.2011. Photograph Stephen Thompson

During the 12 years Macquarie was in Australia the population increased from 11,590 to 38,778 and economy flourished. During his period a beginning was made in the manufacture of cloth and linen, hats, stockings, boots and shoes and common pottery. The Bank of New South Wales had been established and the state of the colonial currency improved with rum being outlawed as a currency. Two hundred and seventy-six miles of roads had been constructed and many churches, barracks and other buildings had been completed. When Macquarie arrived in New South Wales the place was still little better than a prison camp. When he left it was a harbour side Georgian town with every sign of rapid growth before it. Macquarie’s occasional touches of pomposity, vanity, and obstinacy now seem of little consequence. He was untiring in the conscientious undertaking of his duties, and his innate kindliness and humanity led Colonial society from the general brutality of the period. His reward was the affection of the emancipists for whom he had worked so hard, and even John Macarthur, one not easily pleased, could say of him that he was a man of unblemished honour and character. Manning Clarke has conferred on him the title “Father of Australia”.

The watercolour has historical significance as a rare portrait and an object related to probably the most important figures from the early colonial period who brought civil administration, arts and architecture and a humanising and egalitarian influence that transformed New South Wales from a gaol to a Colony, thus ensuring the delivery of a fledgling Australia from ruin and its transformation into a flourishing maritime and pastoral economy that helped to build an expanding British global empire.

The watercolour has aesthetic significance in the portrait of Lachlan and Elizabeth Macquarie, the design of the frames and the portrayal of costumes of the period.

The watercolour is significant for researchers as it is one of the few existing good examples of a hand made keepsakes from early colonial Australia and Britain.

The watercolour has intangible significance, being an iconic object and a symbol of Australia’s brutal convict origins and the development of the early settlement at Port Jackson into a flourishing colony.

The watercolour is well provenanced and documented. It was donated to the Mitchell Library by F.W. Lawson in 1928 and has been in the Mitchell collection ever since.

The watercolour is extremely rare. It is one of a few existing miniature portraits of Lachlan and Elizabeth Macquarie. It is also rare object from early colonial Australia.

The object represents a time early in Australia’s history when the colony was still establishing itself and exploring its new environment. The watercolour also represents the coming of Europeans to Aboriginal Australia as it is an instantly recognisable early 19th century keepsake from early Sydney. The watercolour is in excellent condition for its age and material.

The watercolour interprets the near failure of the colony at Port Jackson in the 1800s and the role of Governors and good administration in the establishment, survival and eventual expansion of the early colony at New South Wales. It also interprets the change from the brutal convict origins of European Australia to a migrant based market based economy.

Bibliography

Clark, M 1987, The Age of Macquarie, Sydney.

Coupe, S & Andrews, M. 1992, Their Ghosts may be heard: Australia to 1900, Longman Cheshire, Sydney.

Hughes, R 1987, Fatal Shore, London.

Heritage Collections Council 2001, Significance: A guide to assessing the significance of cultural heritage objects and collections, Canberra.

Websites

Migration Heritage Centre

June 2007- updated 2011

Crown copyright 2007©

The Migration Heritage Centre at the Powerhouse Museum is a NSW Government initiative supported by the Community Relations Commission.

www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au

Regional Services at the Powerhouse Museum is supported by Movable Heritage, NSW funding from the NSW Ministry for the Arts.

State Library of NSW

www.sl.nsw.gov.au