Era: 1840 - 1900 Cultural background: Irish Collection: State Library VIC Theme:Crime Economics

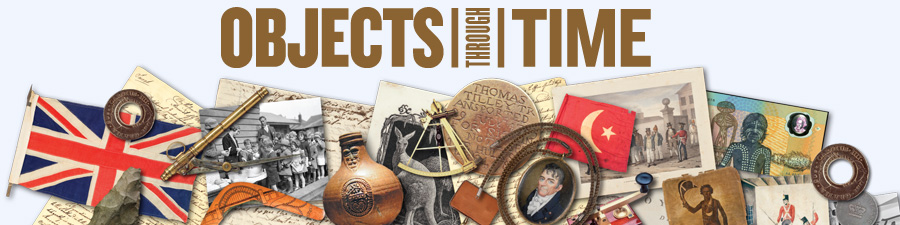

The Jerilderie Letter, 1879. Courtesy State Library of Victoria

Collection

State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia.

Object Name

Jerilderie Letter.

Object/Collection Description

Only two original documents by Ned Kelly are known to have survived. The most significant of these is the Jerilderie Letter, dictated by Ned Kelly to Joe Byrne in February 1879. It is the only document providing a direct link to the Kelly Gang and the events with which they were associated. Approximately 8000 words long, this letter has been described as Ned Kelly’s ‘manifesto’. It passionately articulates his pleas of innocence and desire for justice for both his family and the poor Irish selectors of Victoria’s north-east. The Jerilderie Letter brings Ned Kelly’s distinctive voice to life, and offers readers a unique insight into the man behind the legend.

Bushranging, a form of guerrilla banditry, had initially been a form of escape from and revolt against the convict system between 1790 and 1830. Then in the mid to late 19th century bushranging re-emerged in response to new issues. The principal reason was the gold rushes. Gold was transported along poorly policed rural roads that were easy picking for bandits. The Gold rushes also made rural squatters wealthy with the new markets and increased production the gold rush brought. Concurrent to this was the influx new political ideas brought by migrants travelling to the diggings from Europe, Asia and America.

Bushranging was the manifestation of rural poverty and political rebellion played out against the backdrop of the struggle between the eminent landowners of New South Wales and Victoria who plotted to transfer power from Downing Street London to themselves, only to see it usurped by their political enemies – the artisans, shopkeepers, merchants and renegade gentry whose power base, in the 1840s and 50s, was Sydney. In New South Wales, the march of democrats and liberals came up against the landed gentry with its own history and deep-rooted traditions, determined to have responsible government on its terms – a narrowly representative autocracy – and pledged to stem “the flood of democracy” at all costs. Their weapons were the law courts, banks and the legislature.

In New South Wales, cattle stealing had long been common in squatting districts. In some cases small selectors crossed from petty theft to all out bushranging when the police cracked down on cattle stealing.

By the 1860s, there was more wealth in rural districts to attract organised crime. Bushrangers like Ben Hall and Frank Gardiner survived partly because small selectors assisted and protected them, as did rural farm workers. When Hall’s gang shot it out with two larger squatters, Henry Keightley and David Campbell, station workers made no move to support their employers. When the bushrangers proved able to outwit the New South Wales police, they became heroes to much of the Sydney populace as well. There were tumultuous scenes at the conclusion of Gardiner’s trial in 1864, and over just two days in the previous year, 14,000 people had signed petitions in an attempt to save two other flash (show off) young bandits from the gallows.

In Victoria selection was more successful, but small farmers still experienced environmental hardship and disadvantage at the hands of wealthy land owners, Victorian Government policies and legislation and the Police. Rural banditry and petty theft in north eastern Victoria at the end of the 1870s had a defiant political aspect to it.

With the decline of the Ovens gold fields, large numbers of ex-miners sought to establish themselves on small farms in north eastern Victoria, in the region around Benalla, Wangaratta and Beechworth. The land under cultivation rose from 22,000 acres in 1860 to 163,000 in 1883, yet the small farmers fell into such arrears that over seventy per cent of the land selected after 1872 took more than two decades to purchase.

Families lived in wattle and daub huts with earthen floors, and poverty drove them to break the Selection Acts that were supposed to protect them. After bad seasons or when farm prices fell too low, men violated the residency requirements of the Act by leaving their farms to find temporary jobs such as shearing or farm labouring. This work could take them away from their farms for up to five months, usually at the most important times for farming harvesting and shearing. The women and children were then left to cope in the running of the farm. This led to many cases of sexual harassment, corruption and exploitation by police.

Hardship drove the selectors to other forms of lawlessness, such as burning squatters’ fences and retrieving impounded livestock. Some of the remote police stations reported that they had been stoned, the managers of the commons were harassed and the manager of the Barnawartha Common had his sheds and harvest burnt by selectors irate at rates charged for commonage (grazing on common lands). The region’s remoteness from Melbourne and Sydney bred a sense of indifference and hostility toward the colonial authorities; at the same time the farmers’ remoteness from each other inhibited effective political organisation. Politicians who won their votes lost interest in selector interests upon election, while farmers’ unions were not effective before the eighties. In 1878, when the legendary Kelly outbreak began, grain prices were falling and bad weather was damaging crops.

It was natural to look for anarchistic individual solutions, to regard cattle theft as legitimate, and to protect bushrangers. Groups of young selectors’ sons formed mobs, whose flash poses and love of ‘borrowing’ horses shaded into more clearly criminal behaviour1.

The police, meanwhile, were closely allied with the squatters; the officers mixed with them socially and the force was ever-eager to pursue alleged cattle thieves because of the substantial rewards on offer. Police morale was abysmal throughout Victoria and New South Wales, corruption was rife and discipline was arbitrary. Cost cutting meant dismissals rather than fines or transfer whenever the Chief Police Commissioner wanted to reduce police numbers.

Ned Kelly’s family was part of a wider clan with a history of horse theft and clashes with the police, while the authorities for their part conducted a campaign of harassment against the Kelly’s. The combination of economic hardship, crime and harassment let Ned’s mother to forfeit her selection for arrears in rent in the same month as she stood trial on dubious charges of aiding and abetting an attempted murder. A former police trooper wrote in a Queensland newspaper:

You will find hundreds of such families around any township in these colonies — poor devils, not originally bad, until a fussy or an ignorantly ambitious policeman makes them so for some one of these mistakes, which are often magnified into crimes…2

The government and squatters were alarmed at the degree of public sympathy for this gang of outlaws. One local paper estimated that eight hundred men were ready to support the Kellys, and the sympathy cut across racial divisions, with local Chinese helping to supply the gang. There are even claims that the Victorian Aboriginal trackers first employed in the pursuit ‘were sympathetic to Kellys and were leading [the police] around in circles’ though other accounts suggest the trackers simply wanted to avoid shoot-outs. Queensland black trackers arrived to replace them. More than a hundred years later, some of these Queenslanders’ descendants were to take out writs alleging that they had never been paid, and claiming damages.

Portrayals of Ned Kelly as a political republican rely on oral sources, and are impossible to confirm. It does appear that elements of Irish republicanism, and recollections of the convict era, merged with contemporary grievances to provide at least a quasi-political rationale for the Kelly outbreak. Ned’s Jerilderie Letter harked back to the penal settlements where:

More was transported to Van Diemens Land to pine their young lives away in starvation and misery among tyrants worse than the promised Hell itself. All of true blood, bone and beauty, that was not murdered on their own soil, or had fled to America or other countries to bloom again another day were doomed to Port Macquarie, Toongabbie, Norfolk Island and Emu Plains, and in those places of tyranny and condemnation, many a blooming Irishman, rather then subdue to the Saxon yoke, were flogged to death and bravely died in servile chains, but true to the shamrock and a credit to Paddy’s Land. Ned Kelly, Jerilderie letter 1879.

In reality sympathisers and even people closely connected to the gang came from a diversity of nationalities including Irish, British, German and Australian born. It is interesting that Kelly chose to cross the border into New South Wales to rob the bank, destroy the mortgages of local selectors and draft his manifesto. This may have been to gain the attention of liberal power brokers in Sydney in his campaign against the Victorian wealthy landowners and the Police they controlled.

Following the gang’s capture, the Melbourne populace showed its sympathy with demonstrations, including an eight thousand-strong mass meeting at the Hippodrome which demanded a reprieve. Shortly after Ned’s execution someone fired a shot during a demonstration outside the Glenrowan police station. For several years, tensions remained high in north eastern Victoria between Kelly sympathisers and the authorities, while official policy denying sympathisers the right to select land nearly led to a second rebellion. Later the policy softened, and the economic prosperity of the 1880′s saw the tensions fade. Those selectors who managed to survive as farmers gradually became a conservative social force in the following decades.

The Kelly armour, c.1879. Courtesy State Library of Victoria

Ned Kelly was born in June 1855 at Beveridge, Victoria, the eldest son of John (Red) Kelly and his wife Ellen, née Quinn. His father was born in Tipperary, Ireland, in 1820 and sentenced in 1841 to seven years’ transportation for stealing two pigs. He arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in 1842. When his sentence expired in 1848 he went to the Port Phillip District, where on 18 November 1850 he married Ellen, the eighteen-year-old daughter of James and Mary Quinn; they had five daughters and three sons.

Ned attended school at Avenel until his father died on 27 December 1866. Left indigent, the widow and children moved to a hut at Eleven Mile Creek, about half-way between Greta and Glenrowan in northern Victoria, where James Quinn had taken up a cattle run of 25,000 acres (10,117 ha) of poor country in 1862. Well known in the district, the Quinns and two Lloyd brothers, who had married into the family, were suspected by the police in connexion with thefts of horses and cattle. In 1869 Ned was arrested for alleged assault on a Chinaman and held for ten days on remand but the charge was dismissed. Next year he was arrested and held in custody for seven weeks as a suspected accomplice of the bushranger, Harry Power, but again the charge was dismissed.

In 1870 Kelly was convicted of petty offences and imprisoned for six months. Soon after release he was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment for receiving a mare knowing it to have been stolen. In 1874 he was discharged from prison and his mother married George King. Kelly worked for two years at timber-getting but in 1876 joined his stepfather in stealing horses.

The Kelly family saw themselves as victims of police persecution, but as they grew up the boys were probably were involved in the organised thefts of horses and cattle for which the district was notorious. Ned’s younger brother, James was sentenced to five years gaol for cattle stealing in 1873; released in 1877 he went to Wagga Wagga where he was sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment for stealing horses. He lived respectably after his release from gaol and died in 1946 aged 90. His mother, always known as Mrs Kelly despite her second marriage, died in 1923 aged 91. The third brother, Dan (1861-1880), had been sentenced to three months’ imprisonment in 1877 for damaging property, and soon after his release in 1878 a warrant was issued for his arrest for stealing horses.

On 15 April 1879 a Police trooper named Fitzpatrick went to Mrs Kelly’s home, allegedly to arrest Dan. While there Fitzpatrick, who had a reputation for corruption and unethical behaviour, claimed that Ned Kelly shot him; although Ned was probably not there at the time. The true facts have never been satisfactorily established. Dan went into hiding; Mrs Kelly, her son-in-law, William Skillion, and a neighbour, William Williamson, were arrested and charged with aiding and abetting the attempted murder of Fitzpatrick. In October they were tried at Beechworth and convicted. The judge, Sir Redmond Barry, sentenced her to imprisonment for three years and the two males for six. Rewards of £100 were offered for the apprehension of Ned and Dan Kelly, who went into hiding in the Wombat Ranges near Mansfield. They were joined by Joe Byrne from Beechworth, and Steve Hart, a daring horseman from Wangaratta.

Soon afterwards Sergeant Kennedy and Constables Lonigan, Scanlon and McIntyre set out to capture Ned and Dan, and on 25 October camped at Stringybark Creek where they were seen by Ned. Next day Kennedy and Scanlon went out on patrol, leaving Lonigan and McIntyre at the camp. The Kelly gang surprised the camp and when Lonigan drew his revolver Ned shot him dead. McIntyre surrendered. When Kennedy and Scanlon returned, they did not surrender when called on, and in an exchange of shots Ned killed Scanlon and mortally wounded Kennedy. Ned later shot him in the heart, claiming it was an act of mercy. McIntyre escaped to Mansfield and reported the killings.

On 15 November the Victorian government outlawed the Kelly gang and offered rewards of £500 for each of the gang, alive or dead. Police were mobilised but their methods of pursuit and of obtaining information were crude and inept. On 9 December the Kelly gang took possession of a sheep station at Faithfull’s Creek, about four miles (6.4 km) out of Euroa, locking up twenty-two persons in a store-room. While Byrne guarded the captives, the other three went to Euroa where they held up the National Bank, taking £2000 in notes and gold. This crime resulted in a doubling of the reward, but on Saturday, 8 February 1879, the gang struck again, this time at Jerilderie, NSW, a town about thirty miles (48 km) north of the Murray River. They locked up two policemen and took possession of the police station, remaining there until Monday morning. Wearing police uniforms, they held up the Bank of New South Wales for £2141 in notes and coin, and rounded up sixty persons in the Royal Hotel next door. Ned dictated a written statement of over 8000 words to Joe Byrne and the transcript was sent to Victorian politician Donald Cameron to present Kelly and his family side of the story. The transcript became known as the Jerilderie Letter.

The reward for the outlaws was increased to £2000 a head and black trackers were brought from Queensland. Aaron Sherritt, a friend of Joe Byrne’s, became an agent for the police, and on Saturday, 27 June 1880, was shot dead by Byrne in his own doorway near Beechworth, while the four constables assigned to guard Sherritt hid in a bedroom. Byrne and Dan then joined Ned and Hart at Glenrowan, where they took possession of the hotel run by Mrs Ann Jones and detained about sixty people. The outlaws foresaw that a special train would be sent from Melbourne on Sunday night, and would arrive at Glenrowan early on Monday, 29 June, and with the intention of wrecking it they compelled two railway workers to tear up some of the rails. The scheme came to nothing because a schoolmaster, Thomas Curnow, whom Ned had allowed to leave the hotel with his wife, child and sister, gave warning to the train crew. The other outlaws were equipped with armour made from plough mould-boards and Ned was protected by a cylindrical headpiece, breast and back plates and apron weighing about 90 lbs (41 kg). Little sleep and much consumption of alcohol affected their judgement and, although the armour limited their movements and use of firearms, it gave them a false sense of invulnerability. Under Superintendent Hare, the police surrounded the hotel and shooting began. Hare was shot in the arm and Ned wounded in the foot, hand and arm. Dan, Byrne and Hart took refuge in the hotel and Ned went into the bush. The police continued to fire; Byrne was shot in the thigh as he stood at the hotel bar, and bled to death. About 5 a.m. Ned returned, still clad in armour, looking huge and grotesque in the early mist. He was brought down by bullet wounds in the legs.

Most of the captives in the hotel had succeeded in leaving the building, the last of them emerging about 10 a.m. An old man named Cherry was in a detached kitchen, fatally wounded by a police bullet; young John Jones, son of the hotel-keeper, was similarly shot in the abdomen and died in hospital. With Ned captured and Byrne dead, only Dan and Hart were not accounted for, but the police continued to fire sporadically until 3 p.m., when a policeman set the building on fire. Father Matthew Gibney went into the burning building to administer the last rites and reported three dead bodies were inside. One, Byrne’s, was brought out by police. The other two were those of Dan and Hart, who had apparently taken poison and were burned beyond recognition.

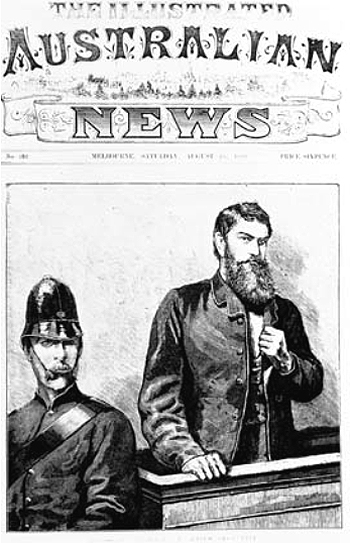

On 28-29 October 1880 at Melbourne Kelly was tried for the murder of Constable Thomas Lonigan at Stringybark Creek. He was found guilty and the judge, Redmond Barry, sentenced him to death.

The Illustrated Australian News, c.1880. Courtesy National Archives of Australia

Despite strong agitation for a reprieve Kelly was hanged at the Melbourne gaol on 11 November 1880. He met his end without fear. His last words were ‘Ah well, I suppose it has come to this’.

Legend and myth remains, complementing that of the Vinegar Hill Uprising and the Eureka rebellion creating enduring myths of resistance to authority and capitalism and the yeoman dream of economic independence in rural utopia.

The Jerilderie Letter historic significance lies in the detailed account of Ned Kelly’s troubled relations with the police and offers his version of the events at Stringybark Creek where three policemen were killed in October 1878. The letter is evidence of the intensity of his antagonism towards the police, and his sense of injustice about the police’s treatment of the Irish, the selectors of the area and his family.

The Jerilderie Letter has aesthetic significance in the design, language and the style of a 19th century colonial document. The Jerilderie Letter provides a research tool for historians to explore the culture and politics of the Australian goldfields and rural Irish experience. The letter is evidence of the unrest on the gold fields, the importation of ideas of democracy and emancipation with the migrant miners and the experience of Selectors and the Irish.

Objects from the gold rushes and rural settlement have an intangible significance to many regional and urban communities as it is a major theme in Australian history and many communities can trace their family history to the gold rushes.

The Jerilderie Letter is well provenanced. Once the Kelly Gang had left Jerilderie, Living and the Bank Manager travelled to Melbourne where they delivered the letter to the office of the Bank of New South Wales who forwarded to Cameron. It was then temporarily loaned to the police in July 1880 and copied for use in Kelly’s trial. This copy was lodged at the Public Record Office and the original was returned to Living after Kelly’s execution. The letter remained in private hands until it was donated to the State Library of Victoria in 2000.

The Jerilderie Letter is rare item of correspondence by the Kellys.

The Jerilderie Letter represents the experience of the 19th diggers on the goldfields, colonial government’s attitudes to the economy and democracy and the evolution of the myths surrounding the Irish, rural settlement and the Kelly Gang.

The condition of the object is good given the rarity and fragile nature of the fabric. There is evidence of some foxing, fading and tears around the edges.

The Jerilderie Letter is a powerful interpretive tool in communicating the experience and the treatment of the Irish on 19th century rural society.

Footnotes

Bibliography

McQuilton, J 1979, The Kelly Outbreak, 1878-1880: The Geographical Dimension of Social Banditry, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne.

Heritage Office & Dept of Urban Affairs & Planning 1996, Regional Histories of NSW, Sydney.

Heritage Collections Council 2001, Significance: A guide to assessing the significance of cultural heritage objects and collections, Canberra.

Websites

bushrangers.htm

www.slv.vic.gov.au/collections/

treasures/jerilderieletter1.html

Migration Heritage Centre

September 2007 – updated 2011

Crown copyright 2007©

The Migration Heritage Centre at the Powerhouse Museum is a NSW Government initiative supported by the Community Relations Commission.

www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au

Regional Services at the Powerhouse Museum is supported by Movable Heritage, NSW funding from the NSW Ministry for the Arts.

The State Library of Victoria is one of Australia's oldest cultural institutions. It is the major reference and research library in Victoria, responsible for collecting and preserving Victoria's documentary heritage and making it available through a range of services and programs.

www.slv.vic.gov.au