Jewish

Budapest, Hungary

Marseilles, France on 28 May 1957

Sydney in June 1957

Rental house with relatives in Randwick, Sydney

Labourer at Eveleigh locomotive workshop near Redfern, Sydney

I worked at Darrell Lea, Dicky Metal, Accessocraft and later became self-employed in the clothing accessories trade.

I was born in Budapest, Hungary in April 1932, and named Ivan – a Russian name – by my father who had been in a prisoner-of-war camp in Siberia (Vladivostok, Russia) during World War One. He eventually returned to Budapest via China, which is where I happily grew up, attending the local Jewish high school.

Everything changed with World War Two. In 1944 first my father then my mother were taken to concentration camps. My sister, Tamara – another Russian name – and I were moved into a protected Red Cross house. We stayed there with our grandparents and other relatives. On 6 January 1945, we were all moved into the ghetto by the Arrow Cross (the Hungarian Nazis). Fortunately the Russian army arrived 12 days later and freed us on 18 January 1945.

My mother survived the camps and arrived back in Budapest in September 1945, but my father died in a concentration camp in 1944. Everything we owned was taken by the Germans or Hungarians and our original home was reduced to an unliveable empty shell. My mother, who wasn’t the breadwinner before the war, now had two children to take care of. It was hard for her to provide for my younger sister and myself, but I returned to high school and then went to technical college.

The Communists didn’t like people who were well-off before the war. Even though we had lost everything we were still thought of as enemies of the working class and they made our lives difficult.

I went into the army in 1949 as a volunteer to camouflage my background. It was here that I changed my name from Deutsch to Devai, which I simply picked from a phone book. By the time I came out of the army in 1952, I was Regimental Sergeant Major – this rank made life a bit easier for our family. I worked with the unions and various departments of the public service; the Government owned and controlled all positions.

The Hungarian revolution began in October 1956. People I knew from the army approached me to represent them in the Revolutionary Council. This was how my involvement with the revolution started. Many people wanted to leave Hungary but it was not possible in the Communist regime. Now, because of the revolution, it became possible.

My sister and brother-in-law left and went to Austria in November. At Christmas they miraculously managed to source a telephone connection to Budapest. My sister cried on the phone for me to also leave Hungary. She knew that Mum wouldn’t follow her if I stayed in Hungary. After the call from my sister I decided to leave. I managed to obtain false documentation that allowed me to travel to a town close to the border with Austria. Mum was not well enough to flee over the border and we hoped that once I was out we would be able to make arrangements for her to leave too.

Mum was extremely worried about my safety because crossing the border was so dangerous. She thought up a clever scheme to find out whether my crossing was successful. Before I left she gave me a tiny glass ornament of two little doves joined together and told me that whoever brought it back to her would be paid a significant amount of money. That way she would ensure its return and would know I had gotten safely over the border.

By this time the Russians had pulled back and there was no authority in the country. The Hungarian border guards knew that all the secret service people had fled. They had opportunity to help refugees and were happy to accept money for it. Over a period of two months hundreds of thousands of Hungarians left. These guards were our guides and they walked us through the border in the heavy winter.

Half frozen on New Year’s night, my cousin Peter and I crossed the border. We had come through a river in bad weather with only the clothes on our backs. The Austrian border guards welcomed us with hot chocolate and food and organised buses to take us to an inn. With other refugees the next morning they bussed us into Vienna.

After we had been helped over the border I chose one of the guides returning to Budapest and told him that he would be well paid if he took the little glass doves back to my mother. The plan worked very well and when my mother left Hungary about a year later, she brought this ornament with her. I still treasure it.

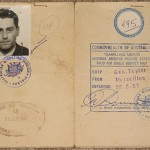

Various organisations in Vienna helped us. We received a special pass showing that we were fluchtlings (refugees). It helped us with things like free travel on public transport and Hias1 gave us food and accommodation. I stayed five months in Austria. The United Hias Service fixed travel for Peter and myself to Australia [where my sister was] and this is my Australian visa.

Salzburg was the starting point of our journey to Australia. More than 1,600 Hungarian refugees travelled on the special train from there to the US naval base in Marseilles, France and then on the US troop carrier, the USNS General Harry Taylor, ready to go to Japan to pick up American troops and take them home. They offered the Australian Government to take as many people as could be processed in time. That was their contribution to the refugee issue and we therefore didn’t have to pay for the journey.

The ship was pretty crowded; conditions were cramped and anti-Semitic feelings flared up between the refugees. The captain decided not to become involved and appointed a group to keep order, a makeshift police force. I was chosen as deputy leader. We soon brought calm and managed to maintain it.

The food on the ship was not to what we were used to. For example, being American, they served baked chicken sweetened with jam. We Hungarians found the tastes to be very foreign to what we were used to.

Our ship was one of the first to come through the Suez Canal and we arrived in Australia in the middle of June 1957. Everything I owned was in this naval sailor bag given to me in Vienna. My total finances were US$10 that the captain gave me for being the projectionist for the officers’ club on the ship. I also had my favourite book of poetry and ballads written in French by author Francois Villon and translated into Hungarian. That was the one thing I brought out with me.

My sister, brother-in-law and his family members had arrived in Australia a couple of months earlier and met Peter and myself. They had a place ready for us in Perouse Road, Randwick where the whole family of nine of us shared quarters. Interestingly, when they came to Australia they came through South Africa because Suez was still closed. The South African community welcomed them and wanted them to stay there. My uncle, who was a master baker in Hungary, was offered a bakery to bake continental bread. The temptation was strong until they found out that white South Africans carried guns for safety. By that time they’d had enough of fear.

We all lived together in our rented furnished house in Randwick. Aunty stayed home and cooked and washed and did everything for us. My first job was at the locomotive workshop at Eveleigh, near Redfern, where I worked as a labourer. The big factory buildings past the railway bridge still stand now and were used as the distribution point for uniforms at the 2000 Olympics where my wife and I worked as volunteers.

My mother was eventually allowed out of Hungary by giving up her rented flat. It took us a further year to bring her to Australia. She left Hungary and first went to London because we couldn’t afford her passage to Australia. She finally arrived in September 1958.

The next three years, as my English was non-existent, I worked as a driver at various companies. The last of these was Accessocraft where I became a sales representative and was greatly assisted by my mentor, Harry Cromer, who helped me to master the business. My other great help was from my wife Judy, whom I married in 1961. I continued [with Accessocraft] to supply the clothing trade with a range of accessories – buttons, fashion trimmings and fabrics – and in the process built up my own collection of agencies from which I retired just two years ago. Judy worked alongside me in the business over the last fifteen years.

Harry invited me to become a member of B’nei B’rith2 in 1963. Judy and I have enjoyed being members as it has brought us great community involvement. In the last 18 years I have been a board member and deputy president of the Coogee Synagogue.

We have two wonderful children, Annette and Robert, and both are married with children. Our bonus in life is being proud grandparents to three beautiful girls and I am now well-known as “Grampsie”.

Australia has been very good to us and home for almost 50 years.

Footnotes

1. Hias was an international organisation that supported Jewish emigration from Europe after the war.

2. B’nei B’rith is a Jewish community organisation focused on human rights and social justice worldwide.

Interviewed by:

Claire Jankelson