German

Hanau, Germany

Bremerhaven, Germany, in March 1958

Melbourne on 5 May 1958

Menindee for 13 months

We stayed with my stepfather’s friend in Broken Hill.

I shovelled coke at the gas company in Broken Hill.

Menindee Water Scheme; painter in Sydney and Broken Hill.

There was not much work in Germany in 1957. I had finished my trade as an apprentice painter and decorator and my brother, mum and stepfather and I had a good talk and decided to migrate to Australia. There was not much work about and we decided to have a go because my stepfather had a friend there. He met Tony Dunkiert in the army in Germany; I call him “Uncle” because I knew him as a little boy. He came to Broken Hill in 1948 and was a guarantor for somewhere to live and work; he gave us work and somewhere to live in [his] house.

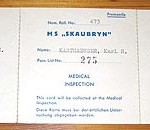

We sailed from Bremerhaven on the Skaubryn in March 1958; we took mainly clothes and kitchen items in a big trunk but it’s now all gone. All I finished up [with] in Australia was jeans, thongs and a Hawaiian t-shirt. That’s all I had.

We had a good journey to the Suez Canal but when we came to the Indian Ocean our ship caught fire because of an electrical fault in the engine room. Two days later we were supposed to go across the equator, so we were actually having a fancy dress get-together when the alarm went and everyone was told to abandon ship, women and children first.

When the Skaubryn was burning I heard this screaming and one of the doors was open and smoke was coming out. I knew the sound was coming from below and I thought there was a stairway going down. I was wearing a chain with St Christopher around my neck; an old girl-friend in Germany had given it to me as a good luck charm. And if it wasn’t for that medal I might not be here today.

When I went over to the door, the smoke was so thick I could hardly see and the chain around my neck got caught on the lever of the door. Next minute I felt a hand on my shoulder and a man said to me, “don’t go”. I said, “why?”. He said, “it’s a chute that goes straight down to the engine room”. I think St Christopher saved my life!

Everyone went to the lifeboats but half of them were rotten. People jumped in and went through the bottom. We decided to [take care of] the women and children and my brother and I stayed back and caught the last lifeboat.

I saw the captain in a motor-boat [with] five [crew members]. They just took off but we still had crew members giving a hand to get passengers on the lifeboats. Normally there should have been 80 people to a boat, but we had 1,400 to save, including passengers and crew. We swam roughly eight hours in the water alongside the lifeboats, hanging on to a bit of rope.

We got picked up by an Australian ship called City of Sydney about eight-and -a-half hours afterwards. We watched a shark circling around the Skaubryn for the next two days so we thought we had been lucky. I hate swimming in the sea now! We were all safe but we lost one person through a heart attack when he got on the City of Sydney . He said, “thank God this is over”, then collapsed and died. We had to bury him at sea.

The Skaubryn stayed afloat but burnt out completely. The City of Sydney hung around for a couple of days, moving around the burning ship. The City of Sydney was a tanker; full of kerosene and dangerous. We were not allowed to smoke. I pinched a couple of [cigarette] cartons from the store room and I shared them around with the people on board.

We were transferred to the Roma, a passenger ship from Colombo (Sri Lanka) and it took us back to Aden in Egypt. We stayed there for two weeks in a brand new building of the Queen Elizabeth Hospital. The Government opened it up for us and some of the people there gave us English tuition. Our class was held in the morgue; there were no dead people but that was the only area in which the classes could be held.

We had a few up and downs in Aden but eventually a Dutch ship called the Johan Van Oldenbarevelt came across and picked us up and took us to Fremantle where we stayed for two days, I think. My family coped because they had been through the Second World War – we just carried on. Then we left for Melbourne and we arrived there on 5 May 1958.

It was good to get into contact with the people that we knew. We travelled to Adelaide by train and stayed overnight at private accommodation [arranged by] the Salvation Army. They put us back on a train to Broken Hill. I arrived in Broken Hill on 7 May. Everybody said to me I was bloody mad because I was wearing shorts and a t-shirt. They thought there was something wrong with me because I didn’t feel the cold.

The town was a shock because it wasn’t as green as we expected [and] there were not many stone buildings. All we could see was this wood and iron but later I realised they was easier to build than stone. Then I saw the Trades Hall and Town Hall and they were equal to the architecture of Germany.

The language was a bit difficult [and] there were a few chaps in town who tried to help me. They taught me the wrong words and I was very embarrassed sometimes! There were not many Germans in Broken Hill when we arrived; mainly Poles. There were eight or ten Polish people that came with my uncle in 1948. They came from the Snowy Mountains Scheme and came to work on the Menindee Water Scheme.

My first job in Broken Hill was working at the gas company shovelling coke; I couldn’t get a job as a painter. I stayed on for about two weeks and then my brother and I got a job in Menindee with the water [scheme]. My brother and I helped to build the Parnarmaroo Weir and Inlet out of concrete; my name is carved at the bottom of the main weir. We stayed in a [Government-run male workers'] camp in Menindee for three months. We went to the cafeteria and you have your meals and everything but it was just one bedroom little huts. They just built them row after row; there was about 200 of them, I think.

We made some extra money. There was another German fellow there and we became friendly with him. On weekends and some nights we had a contract with him to go and catch rabbits [and] doubled our wages. They had to be cleaned and dressed and I got five shillings a pair.

While we were in Menindee, work ran out for my stepfather [in Broken Hill] and they (mother and stepfather) decided to go to Sydney. The foreman of the camp at Menindee was an Englishman who wasn’t very fond of “new Australians” because they couldn’t speak the language, so we decided to go to Sydney [too]. I got a job there as a painter with a Dutch firm in Sutherland. I spent nine months there and then my boss said, “it gets very wet in the winter here. You’ve got three weeks holiday coming. Take the three weeks and there’ll be plenty of work when you come back”. I notified my aunty in Broken Hill to say I was coming back for a holiday. And I’m still here!

The Immigration Department said to stay in one place for two years and if you didn’t like the place, you could return to Germany. I enjoyed Australia and I wrote to my girlfriend [in Germany], “I’m not coming back; I’m staying here”.

Some people asked me where I came from and said I must be one of those “Nazi bastards”. I always told them, “I’m German-born but I’m an Aussie. I’ve got papers to prove I’m an Australian citizen, have you?”. They usually say “no”. There still is some animosity.

If you go around Broken Hill, I would say 90% of the work has been done by migrants. Ten per cent by Australians, but apart from a few Aussies, all the workers have been migrants.

I got a job with Ivan Kolinac [Senior in Broken Hill]. He said he would give me a job for a fortnight. The fortnight lasted 22 years. If he was alive today and in business, I would still be working for him. He was a top man.

I went on my own in 1983 and started a partnership with Gary Schipanski. Gary and I had weekend work on the side and Ivan never questioned us but said, “make sure you buy the paint from me!”. So we carried on from there and we are still in partnership today.

In the early 1960s I was working for a contractor, painting a bank in Broken Hill. I’m a bit shy and asked this girl would she like to come out with me and she said, “just a minute”. She raced upstairs. I don’t know what she was doing upstairs. Anyway she came down and I was standing at the bottom. She missed a step and she fell for me! I’m telling that story and I’m sticking to it! I married Liz in 1965. We have two children. Andrew is an electrician in Albury and Kathryn is a nurse in Wagga Wagga. She married a local-born Yugoslav whose parents settled in Broken Hill.

When I met Liz’s parents, I was wearing a pair of jeans and a Hawaiian shirt that I bought in Aden, a pair of thongs and a blue and white striped cardigan that the Red Cross had given me. I wasn’t very impressive! Everyone says you can get rid of your mother-in-law but I would always want my mother-in-law back; she was a top person. She always stuck up for me.

Through Ivan I met a lot of Yugoslav people and joined Apex and that helped me a lot. I gained more confidence in presenting myself. Apex is a service organisation that helps other people and I was fortunate to [be there] when they raised funds to build the Home of Compassion. I really became part of the Broken Hill community as a member.

I still help other people. Liz is a member of the Quota Club. She does a lot of charitable work and the menfolk are called on to give a hand.

I’ve been back to Germany twice. I went back in 1981 with Liz, Kathryn and Andrew. I still have [family] living in Germany. My father died in the Second World War in 1941. He’s buried in France.

Broken Hill has given me a good life; a steady income; employment. The people here in Broken Hill have given me a lot of assistance. I still have difficulties sometimes with the language.

When I first arrived, I had a lot of discrimination from other people, mainly Australians, but now, 44 years later, I have no difficulties at all. I seem to have got used to the style of Broken Hill. It was very easy to become part of [it]. I love the bush; the freedom and the space. I can go out and lie under the stars; it is beautiful. When I die, bury me out there.