Romanian

Semlac, western Romania

Genoa, Italy on 1 August 1950

Newcastle, Hunter region, NSW on 15 September 1950

Tent at Greta (Hunter region) for one month, tent at Cunnamulla (Qld) for one year and workers’ barracks at Mt Isa (Qld) for four years.

31 Queen Street, Revesby in SW Sydney

Paroo Shire Council, Cunnamulla in SW Queensland doing road repairs and other council jobs.

Cane cutting and construction in northern Qld; machinist at Borg Warner in Queensland; mining at Mt Isa, Qld; quality assurance at Tubemakers in Yennora, SW Sydney.

I was born on 26 January 1926 at Semlac, which was a small town in Arad county in western Romania. It is about 600 kilometres from the capital city of Bucharest and close to the Hungarian border. My parents were Romanian and I was an only child. We lived in a small place named Nadlac, right on the Hungarian border, where my father was the manager of a horse stud farm. We left there in about 1936 and went to Timisoara, where he worked with a friend who was a veterinary surgeon.

My primary schooling was done at Nadlac and Semlac. Then I went to high school in Timisoara, finishing there in 1946 – soon after the end of World War Two. Romania had tried to remain neutral in the war but finally was forced to fight on the side of the Axis, to whom it was invaluable in that it was very rich in oil. Romania also aimed to regain its lost territory, Bessarabia, which the USSR had taken from Romania. Later, on 23 August 1944, Romania joined the Allies and on 30 December 1948, King Michael was forced to abdicate and Romania became a republic under Communist rule, after which began years of serious political unrest and persecutions.

I decided to leave my country and seek peace elsewhere. On 21 October 1947, I left Timisoara and travelled to Brno in Czechoslovakia to study engineering. My stay was cut short when a coup took place in February 1948 and the Communists took over, so I had to move on. I went to Prague to the Romanian Consulate trying to find out the situation back home and was told to move on as they were doing the same.

In Brno I met a fellow Romanian on the run and a Romanian who was a Czech ethnic. We were all thinking of leaving Czechoslovakia, so some time in December 1948 we left Brno and went to a town close to the Austrian border, where the relatives of the Czech ethnic were living. We gathered all the information we needed about the border layout and during the night we crossed into Austria, illegally of course.

The crossing of the border did not go exactly to plan although we had a compass. We missed the railway station by about a kilometre and missed the morning train to Vienna. We became confused because we crept through vineyards which had posts and wires. Those wires daunted us as we had to go around them and in doing so became somewhat lost, but finally we arrived at the station.

My Czech-Romanian friend spoke German and explained our plight to the station master who directed us to a room in which to wash up. He also gave us something to eat. He told us to remain in the room until he knocked on the door and then we were to board the train as it was about to depart. We trusted him and did as we were told. At last we were on our way to Vienna, little realising that it was in the Russian zone of Austria.

My Czech friend knew an old lady who lived there and we went to her house and slept the night with our heads on the table. We had purchased much in the way of clothing and cigarettes in Czechoslovakia with the last of our clothing coupons and we left some of our clothes there until we could return to collect it later.

We went to the railway station as we wanted to try and get to the American zone, but here we were tricked when we paid to get out of the Russian zone. We ended up on a bus to St Valentine and the bus driver told us that this was as far as he would go. He left us in front of the Russian military headquarters, where once again we were faced by Russians. They confronted and questioned us, and took our cigarettes and my very sophisticated compass. After a week or so we were taken by truck to Wiener Neustadt (Vienna’s New Town) and placed in a Russian army repatriation camp. Here we met two Romanian Jews, one Austrian of Czechoslovakian origin, one Bulgarian and one Yugoslav. Some time later all of us were taken to Vienna West station and put on a train. I still have the train ticket I used. The Austrian of Czech origin was a railway employee and he told me that the train would stop only at Chop station and then somewhere in Russia.

Onboard the train we were placed in the middle carriage and we looked for a means of escape. We were pretending in front of the Russians that we were happy to be going back to our country.

The guard went to his comrades and we were all alone. Quickly we started to look if the doors were locked or not and were pleased to find them unlocked. Looking out through the window we saw a long bend in the track and jumped out, four at a time, arranging to meet again at Vienna West station should we make it. This was in late December and the snow was quite deep so it was not such a hard landing.

We rolled down the embankment and lay still until the train was far away. We heard later that some of the escapees had been shot from the train. We reached a larger town and found that the bus to Vienna would leave that afternoon. A local gave us some money to top up our fares back to Vienna. At 5pm that day all of us met at Vienna West in the Russian zone, right back where we had started from.

Here, after much determination, we found our way to Salzburg, where we knew there was an office of the International Refugee Organisation (IRO) who may be able to help us. In Salzburg the conditions for refugees were inadequate and we were told that Munich IRO was a lot better organised. With a bit of luck we got to Munich [and] went through the usual procedure of interrogation. We were given our Displaced Person status and from there we were sent to a refugee camp in Dachau. In Dachau every new arrival had his/her medical check up. I was found to be badly malnourished and spent about six months in the camp’s hospital.

It was here that we found the Russian Communist flag. There had been a demonstration of some sort and the flag was flying from a building. We took the flag and tore it into 40 or 50 pieces so that each person got their little square. I still have my piece of red flag and it is a constant reminder to me of my reasons for leaving my homeland. The Russians had been the cause of my leaving there and by stealing the flag it was my way of getting even with them. It was my way of maliciously snubbing my nose at the Communists who caused so much havoc in Europe during and after the war.

I wrote to some relatives in the USA and they commenced proceedings to sponsor me, but because I had to wait a long time I decided to go to the Australian Immigration Commission in Munich. I was accepted and had to sign a two year contract that I would work wherever I was sent.

We then went to Bremerhaven, where there was a large refugee camp which contained those who were to migrate elsewhere. On the way, in Augsburg I think, I acquired another of my belongings, some US Army metal cutlery I ‘borrowed’ from the camp as a memento of those days in Germany. On reaching Bremerhaven we were told that we would be sent to Genoa by train as an earlier ship would depart from there.

My thoughts were varied. I had been through so much getting there but my thoughts were also for home. The thought of safety prevailed though and on 1 August 1950, I boarded SS Amarapoora in Genoa, Italy on my way to my new country. Amarapoora had been a cargo ship but was converted to a Red Cross ship, and then to a migrant ship – as many were at that time. I have a photograph of the ship, which has memories of hopefully coming to a better life.

We were 45 days onboard with a brief stop at Colombo [in Sri Lanka], before arriving in Newcastle on 15 September. My thoughts on arriving in Newcastle were that I was grateful to be out of devastated Europe but I had no intention of staying in Australia as I had plans to move on, probably to the USA. In the meantime I had signed a two year work contract with the Australian Government. I was classed as a labourer. I had not much opportunity to obtain a profession in Romania as I was quite young when I left.

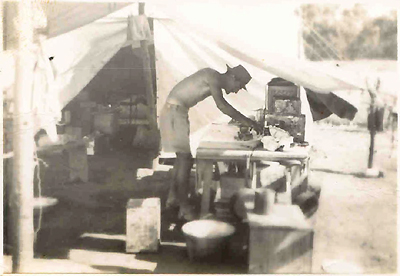

From the dock at Newcastle we were taken by bus to Maitland and then to Greta camp, where we were allocated to tents. I still have a photograph of the tent in which I lived on my arrival in Australia. There at the camp I was issued with a hat, a pair of boots, a coat and five shillings. Half of the money was spent on having my hair cut and the other went to cigarettes.

My first job in Australia was with Paroo Shire Council at Cunnamulla in south-western Queensland, where I worked for a while on road repairs and later in the office. Here I was accommodated once again in a tent. Road workers often lived in tents and in some places still do.

In 1951 I came to Sydney on my first annual leave where I met some of my friends from Germany and some from Timisoara. In 1952 I left Cunnamulla for good and came to Sydney but things were not too good here due to a recession which led to large unemployment, so I chose to go cane cutting in northern Queensland, where I remained for about three weeks. I then went to Ingham where I helped in the construction of the sugar plant. I was there about two years and then returned to Sydney. In 1954 I went to Mt Isa, where I worked as a sub-foreman in a lead smelter until September 1958. Here I lived in barracks, in which all the workers lived. Then once again I went back to Sydney, where I married in 1959 and had one son, Gabriel. My last job was Quality Assurance Officer at Tubemakers of Australia in Yennora [in south-west Sydney], where I remained until I retired 27 years later.

I became a member of the Australian Romanian Association (ARA) at its inception in 1951 and have worked continuously for the integration of Romanians in Australia, representing them at a migrant resource centre [and] in refugee programs. Through the Community Refugee Settlement Scheme, I have contributed to sponsoring a large number of Romanian political refugees to Australia.

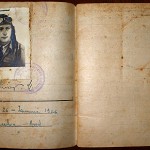

This is my country now and I have no reason to leave it. I have been fortunate in having been able to bring some objects all the way from Romania when I arrived so long ago and they have been of nostalgic importance to me.

The most important item is the handmade handkerchief made by my mother which has accompanied me on my slow and complicated journey from Romania to Australia, the dates of which are recorded in a diary that I brought with me. The handkerchief is made of fine cotton and has drawn thread work and my initials are embroidered on it. It will always remain as my connection with my old country and more so with my mother who died while I was at Dachau. She embroidered four of them in different colours, and I took them when I left home, but sadly this is the only one that has survived.

I also have a lovely wall hanging cloth that I smuggled in. My mother made it and it is of fine linen which has been beautifully embroidered with drawn thread work. I will never part with it.