Jewish

Calcutta, India

Columbo, Sri Lanka in April 1952

Sydney in June 1952

Waverton, Sydney

Dad did labouring jobs and Mum was a secretary.

After university, I became a teacher and storyteller.

I was born in Calcutta, India. My parents were orthodox Jews. My dad’s parents were born in Baghdad and Burma and mum’s dad’s ancestors came from Germany. My [maternal] granny was living with us ‘cause Grandpa was dead. There was no telly, my granny was my entertainment; she was a storyteller.

We lived in the heart of Calcutta in an invisible Jewish ghetto. There was no anti-Semitism; India was paradise for Jews. My dad tells an extraordinary story: one night, Mum was sick so he had to go to the chemist in his pyjamas. On one corner there were Hindus slaughtering Muslims and they said, “Good evening, Sahib”. My dad knew as long as he didn’t interfere they wouldn’t touch him. Next street corner there were Muslims slaughtering Hindus and they said, “Good evening, Sahib”. The Jews were exempt from hate between Hindus and Muslims at that dreadful time of [Indian] partition.

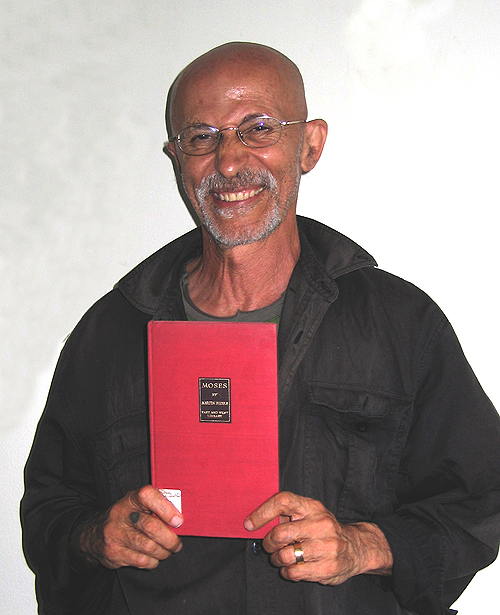

Moses at 18 months, Calcutta, India

“The photograph was taken by Uncle Shalom who was a professional photographer. My mother told me I was in a bad mood and they bribed me by giving the coin held in my left hand.”

When Gandhi kicked the British out of India, the Indians said to the Jews, “You’re not part of the [British] Raj, so you can stay”. Under the Raj, Jews had rights as white people, but now Jews would not have the privilege, so there was a mass exodus out of India. My dad’s younger brother and three of his sisters already happened to be in Sydney. His brother said, “Sydney’s a wonderful place, why don’t you come here?” So my dad came here in 1950.

Two years later my mum, my sister and I came to Australia. My granny couldn’t get a passport or permission for her to come. At the time it was the ‘White Australia’ policy. My dad said it was because she had black skin, but my dad and I were more swarthy. She had starkly white skin compared to us.

[We got] the train from Calcutta to Karachi, [then] the trip from Karachi to Colombo we came by aeroplane. I was eight and had never been in an aeroplane before and vomited. The two things I remember of the boat trip from Colombo: we had fish with mayonnaise sauce (I hated the sauce but I had to eat it!) and me and my sister were in the cabin on the bunks. She was on the bottom bunk and fell out of it!

[Mum] brought [her] cooking pots – scoured, old, dreadful, bloody aluminium things. I remember them clearly. I remember my mum’s big sandalwood box which my brother still has.

We arrived here early June 1952. It was a six week trip. I remember vaguely going across the Harbour Bridge and looking up. My dad, uncle, aunties met us at the boat but I have no memories of it. I must have been excited to see my dad again.

There are two versions of why my granny was allowed to come [to Australia]. The first was when my mother was pregnant with my brother and depressed at living without her mother. It was an act of compassion from the Australian Government. The unofficial version, my dad’s version, but it may need to be taken with a grain of salt because my dad was a glorious storyteller, is that he went to Canberra and bribed someone.

As Jews, we had a British India passport, so when we came to Australia we didn’t have to be naturalised. But there was some deal that if Mum and Dad surrendered their passports they would be given an Australian passport instead, so we swapped citizenship.

So once more we were a family living together. When my granny came here she just hated Australia. We were living at Waverton and she said, “This isn’t a city, this is a graveyard!” Waverton is in the suburbs, whereas in India we were living in the heart of Calcutta. She was so unhappy my mum and dad borrowed money for her to go back [to] India. She found out that India wasn’t the India it was before and wrote, “I want to come back to Australia”, but she never liked Australia at all. Most of the Jews were living in Bondi so we were very isolated.

I think my mum hated Australia too, the isolation. Both my grandparents and parents knew stark poverty when they were young, however in India things had changed; they weren’t rich but they had servants, whereas here they were quite poor. And so my mum was like my granny, she didn’t celebrate Australia at first. Dad, of course, was gung-ho. He was very excited because he wanted to establish a synagogue and was very involved with the community, so he wasn’t as isolated as the rest of us.

Because it was an extended family, Mum and Dad went to work. Dad did all sorts of labouring jobs. Then he met a guy who was his boss in India and he was working for C.I.G. (Commonwealth Industrial Gases) and got him a job there. Mum was a secretary.

Granny was ‘the mother who stayed at home’ so it was really Granny who brought us up, not Mum. Her biggest fear, which came true, is that the kids – me, my sister, my brother – would stray from the orthodox Judaic path, and we all did. Her ultimate horror was that any of us would marry outside the Jewish faith. The first woman I ever lived with was non-Jewish so I never said anything to Mum or Dad until Granny died.

My parents did not want me to associate with any non-Jewish people. There was no Jewish school at the time and, even so, my parents could not have afforded it. I was the only Jewish kid in my entire school, which means I had no friends and my parents actively discouraged me bringing anyone home. I never went to anyone’s home because of the Jewish kosher dietary requirements. I didn’t have any friends until just before my Barmitzvah when I was 13. I had to go to the synagogue at Lindfield every Sunday to practice for it. There was a youth group and, for me, that was the highlight of my life. We’d play games and I was part of a group.

When I finished school I went to uni. Both my parents didn’t have much education, so [it] was a very big thing. Then I became a teacher of English history in high schools, then a teacher of autistic kids for seven years. I had a total meltdown, physical not mental. For about a year I was like a corpse. I could hardly move.

My dad tried to beat God into me, so I hated the Jewish religion. It gave enormous support to my mum, dad and granny but at the time I went to university, I realised for me it was meaningless. I discovered the world of literature, philosophy at uni and my Jewish friends thought I was a freak. They were dreaming of becoming doctors, dentists and buying cars, yachts and playing the stockmarket. At uni I found non-Jewish people that did share my passions, so that was another reason to separate myself from the Jewish community, which I still do.

My parents offered to pay for me to go and see my brother in Israel. The subtext was they were hoping I would meet a nice Jewish girl and get married. In Israel and also in New York I found Jews who were like me and those are the only times in my life I have mixed mostly in Jewish circles. I loved it. That has not been my experience here. That is not to say there aren’t Jews like me here; I simply haven’t met them. The big exception is my brother.

At core I am a Jew. I have a deep, deep love of Kabbalah Jewish mystical tradition and stories but am very disconnected from the Jewish practice of belief. My spirituality is Eastern, not Jewish. When Mum and Dad were alive, of course, I went through this charade of celebrating the Jewish rituals with them, but [now] the only time I celebrate Jewish ritual is when someone in the family dies. I have really cut myself off from the Jewish world.

My dad had a thirst for Jewish knowledge. It was his passion. He got a librarian to catalogue his books in Sydney. He spent years researching his opus on Moses and but never got to write the book. His passion was more scholarly [than mine].

When I went to New York, I met a Jewish storyteller and the doors of storytelling opened for me. For several years I gave very obscurantist performances [in Australia]; one actually only made $20! I realised that there was no way I could make a living as an adult storyteller here and then I decided to explore the world of kids’ storytelling because you could make a living on the school circuit. I really enjoyed it but didn’t have the business skills to sell myself. One day the phone rang and this woman said, “I am starting a booking agency for performers, would you like to be on my books?” I said, “You are the answers to all of my prayers, you are my fairy godmother.” Because of her I have lived from my storytelling for 26 years.

My passion and love and dreaming of becoming a storyteller comes from my granny and Dad was storyteller number two. I tell kids, “There was no telly, the only entertainment I had as a kid was my granny. At night we had two choices: we could sit there bored out of our tree, or we’d look at Granny and turn her on.”

Interviewed by:

Andrea Fernandes, NSW Migration Heritage Centre

31 October 2006