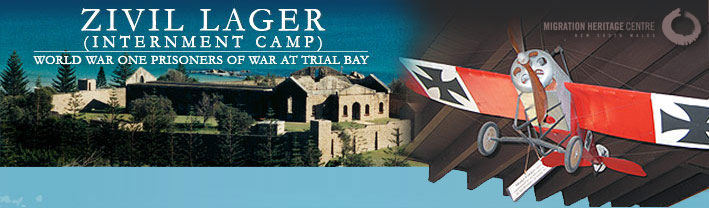

ALIENS AT HOME: THE WORLD WAR I INTERNEES AT TRIAL BAY

Internment

The outbreak of fighting in Europe in August 1914 immediately brought Australia into the Great War. Within one week of the declaration of war, all German subjects in Australia were declared ‘enemy aliens’ and were required to report to the Government and notify their address. In February 1915 the meaning of ‘enemy aliens’ changed. It came to include naturalised migrants as well as Australianborn persons whose fathers or grandfathers had been born in Germany or Austria. Since it was impossible to intern all enemy aliens resident in Australia, the Government pursued a policy of selective internment. They targeted the leaders of the German Australian community — including honorary consuls and pastors of the Lutheran Church, businessmen and the destitute. Some internees had been accused of being disloyal by neighbours or had come to the attention of the police by accident. In NSW the principal place of internment was the Holsworthy Military Camp where between 5000 and 6000 men were detained. Women and children of German and Austrian descent, detained by the British in Asia, were interned at Bourke and later Molonglo near Canberra. Former gaols were also used. Men were interned at Berrima Gaol (constructed in the 1840s) and Trial Bay Gaol (constructed 1886).

Trial Bay Internment Camp

Trial Bay Gaol was not well prepared for the first internees who were accommodated in tents. Early photos show a number of white tents inside and outside of the gaol walls. Most of the internees were finally accommodated in the cells of the two wings. The interned consuls and officers were accommodated in wooden barracks that were located between the walls and the main building. Towards the end of 1916, they were moved to wooden barracks on the outside, to the left of the gaol, overlooking Trial Bay. The Australian Government did not provide all the blankets and bedding required until many weeks after the internees arrived.

Life at Trial Bay

Life at Trial Bay was strictly regulated. Reveille or wake-up was at 6.30 am, sick parade 7.45 am, breakfast 8 am, roll call 9 am, inspection of barracks 10 am, dinner (lunch) 1 pm, roll call 5 pm, tea (dinner) 5.30 pm and lights out 10 pm. Until September 1917, the internees were supplied with the same rations given to Australian soldiers. From September onwards these were reduced to ‘Imperial Rations’, based on the rations supplied to prisoners of war in Britain. The offcial rations were basic but adequate. However, the internees could supplement their diet with vegetables from their own garden, fish caught at the beach and items sold at the canteen. The camp even had a gourmet restaurant, ‘The Duck Coop’, run by an entrepreneurial restaurateur. It offered fine food to internees who could afford it.

The activities of the internees transformed Trial Bay into a thriving place for sport and culture. Leisure and competitive sporting activities were organised by a number of private clubs. The Turnverein athletics club had the largest membership. The boxing, bowling and chess clubs also drew large crowds. Two choral societies performed German folksongs.

While the freedom allowed to internees created a holiday spirit, there was another side to the camp’s daily life: the experience of forced confinement and boredom.

The shock of life in gaol cells created a new identity for men who had been removed from their families and communities. Most of the internees experienced feelings of isolation, and suffered because of the monotony and lack of privacy.

Causes for friction are popping up everywhere and you have to pull yourself together all the time in order to avoid

confrontations. Things get easily out of dimension and people become irritable and touchy due to the long imprisonment.

You just can’t avoid it. Some days the mood is following the course of the war, one day there’s high tension and then again

one is doomed to wait and wait.

- W. Daehne, diary entry, Sunday 21 April 1918, ML

MSS 261/3 Item 18 Relations between internees and camp guards were formal and tense as, unlike the men at Berrima — who lived in the naval regimentation of officers and sailors — the Trial Bay internees were more inclined to protest. This generated ongoing conflict.

In January 1916, internees went on strike after one described by the guards as an ‘unceasing trouble maker’ was sent to Holsworthy for a minor incident.

The most difficult problem of camp life for internees was sexual frustration, engendered by being confined in an all male environment for years on end. The enforced celibacy led to a number of psychological problems. Many internees experienced the symptoms of depression and anxiety disorders. Dr Max Hertz, one of the prominent internees at Trial Bay, who was also camp doctor and an internationally renowned orthopaedic surgeon from Sydney, reported on ‘self abuse’ and the ‘ugly side’ of the sexual question.