Video: Tika Poudel’s migration memories

Video: Tika Poudel’s migration memorabilia

Bhutanese

Dagana District, Bhutan

We walked four days from our home to reach the nearest road, that is the border of India. We stayed in India about ten days, then the Indian government loaded us in a truck and brought us to the Beldangi refugee camp in Nepal, where we stayed for nineteen years.

Melbourne, March 2011

Albury

In 2012, I worked at Albury High School as a student supporting officer and am now working as an interpreter for the Nepalese community.

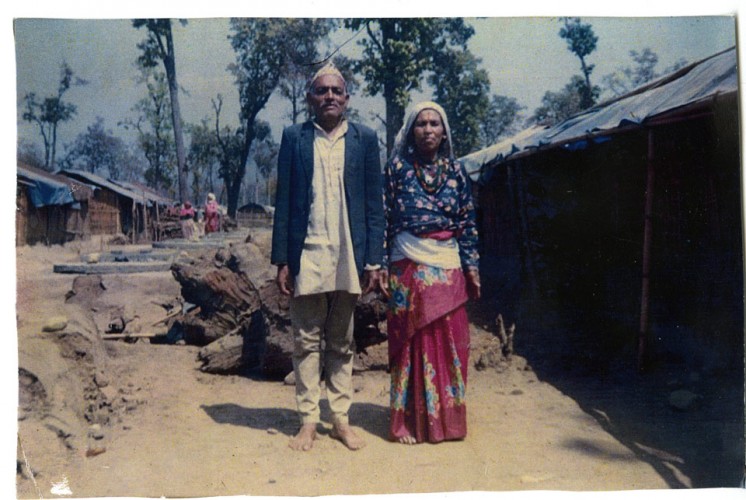

My name is Tika Poudel. I was born in Bhutan in Dagana District, which is between China and India. My birth place was in Dorona [village] block, Dagana District, in Bhutan. It was a very small village where there was no road, no electricity and no facility but it was lovely. There was scenic beauty and we have a very, very big farm, big cardamom garden, lots of cattle, seeds and green field around my house. The house was very, very lovely.

My school was one and half hours away from my village. We have to walk there, walk morning and evening back to our home but after completing Year Five I went to the other junior high school, which is one day away from my home. I stayed in the hostel [at the junior high school] for two years up to 1990. So thereafter I was not allowed to study in that school because there was political instability in the southern part of Bhutan. I was called into the head teacher’s office and he told me to leave the class. At the time there was no phone nor any communication. I was just thirteen years old, so I left everything at this school and I came out of the class and I went towards my home.

In the meantime there was a moment in the country and we were on the policed side. The army used to come to our house and knock at our door and it was very, very scary, yes very, very scary. And some of the villagers were taken to the prisons and beaten heavily, which is too much. Then one day what happened, the head of the district organised a meeting, and they said, ‘We have given three options to you: you have to leave the country immediately, be in jail for thirteen and half years or be ready to get the bullet in the ground.’

So my dad decided to leave the country to save our life. Many bad things happen in the country, rape and torture from the army. We decided to fill out the form, the voluntary migration form. At the time of filling out the voluntary migration form, they took photos. And they compel us to laugh and compel us to smile at the time of taking photos to show to the outside world that we [were] leaving at our own will. We are made to smile even though our heart was aching. Thereafter we went to the headquarters, the district headquarters, and signed the voluntary migration form, forcibly, otherwise they start beating the people. And we leave the house, they had given [us] ten days’ time to leave the country.

After ten days on 2nd February 1992 we left our property, cattle, farm, everything, garden, all the belongings that we had. We carried our bag because there was no transportation. We had to walk four days from our home to reach the nearest road, that is to the border of India. From there my refugee life begins and during the first year of my refugee life three of my cousins were dead because of an epidemic.

The camp situation was very, very hard for people. We had to live in a small room, where everyone has to share the room. There is no privacy, no bathroom, we have to dip in a bucket of water to take a bath and wash our clothes. People are very, very frustrated and we spend this horrible life for nineteen years in refugee camps. The life was very, very torching, there was no electricity, there were no facilities. Luckily we got the basic education. I was a refugee teacher. I was to teach in the refugee camp for twelve years.

In 2007 I applied for resettlement because I didn’t want to make my children part of the refugees. I applied and in 2008 I was accepted by the Australian government because my wife’s parents were already here [in Australia] through the resettlement process. Because of the link, I was accepted to come to Australia. After completing the entire procedure, the medical and everything, I left the camp on 18th March 2011.

I knew Australia was a peaceful place, excellent education, people are helpful and I was hopeful we have life over here. On 21st March 2011, I arrive to Albury. I was very, very happy. I had never had the journey by plane [before], which was very exciting. We enjoyed our trip and we came here with new hope and new thoughts.

I was very, very happy to see a lot of Australian people welcoming me on the airport of Albury. I found a case worker, volunteers, Bhutanese community and all the Australian people welcoming me. I was surprised to see the new house and the basic facilities provided by the government already there.I was in a four bedroom house, which is very, very beyond my expectation. I’m very, very happy and my family is very, very happy. On the other hand, yes, we were a little bit sad because we missed some of our families in the camp.

After my arrival I joined the AMEP (Adult Migrant Education Program) class at TAFE and in 2012, I worked at Albury High School as a student supporting officer. Presently I have been working as an interpreter to my Nepalese community. Finally I would like to give the message to my refugee friends that we have to work hard, study, improve our English so we can make our life better. Because without working hard it is hard to adapt in a new country with a different culture and with different traditions and with advanced technology. That is why we have to work hard, work hard so that we succeed in our life and make our new home a better place.

I’m going to show you some of the important things that we got from our lovely motherland, Bhutan. And these are very precious to us.

![‘This [bangchu] was bought by my Dad during the 1950s … My Dad [died] in the refugee camp so in his memory I have brought this to my new home in Australia.’](../../../cms/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/5-Poudyel-Bangchu-750x500.jpg)

‘This [bangchu] was bought by my Dad during the 1950s … My Dad [died] in the refugee camp so in his memory I have brought this to my new home in Australia.’

This is called bangchu. It is a traditional plate of the Bhutanese people, especially the Nalongs, the ruling party. They used the plate to eat rice and meat, usually they carry it [when] going on a picnic or for carrying the packed lunch. These are never washed. After eating, they are wiped with a clean piece of cloth. They are made out of cane. This was bought by my Dad during the 1950s. In the memory of my Dad, I have carried this to the refugee camp. My Dad [died] in the refugee camp so in his memory I have brought this to my new home in Australia. This is precious to me in the memory of my lovely motherland, Bhutan, and in the memory of my Dad.

This is part of Bhutanese dress. This is a keyra and this is worn by the women for the national dress. They have on a kira and they tie this belt around the waist. This is the belt used by my Mum. We have brought these here and left other things because other things are very, very heavy and difficult to carry to the new place. In the memory of the motherland we have brought this one to this place, this part of national dress.

![‘This [daura and suuwal] is worn by people living in the Southern part of Bhutan, especially of Nepalese origin … We preserve them and use them at the time of festivals.’](../../../cms/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/6_-Poudyel-Daura-Suruwa-750x500.jpg)

‘This [daura and suuwal] is worn by people living in the Southern part of Bhutan, especially of Nepalese origin … We preserve them and use them at the time of festivals.’

This is the Nepalese dress, the daura and suruwal. The Nepalese people at the time of the festival they wear this dress, especially during our festival of Dashain. This dress is worn by the male members. Along with the daura and suruwai, they use a topi and this is the national dress. This dress is worn by people living in the Southern part of Bhutan, especially of Nepalese origin. And all these are special at the time of festivals of Dashain, so we preserve them and we use them at the time of the festivals.

‘In the 1990s there were human rights violations in the southern part of Bhutan. The government adopted ethnic cleansing policies. At the time we were not allowed to worship the Hindu goddess. But my parents kept them secretly …’

These are the Hindu goddess our grandparents worshipped from the beginning of their lives. These statues were bought in the 1950s and they were valuable to my parents. In the 1990s there were human rights violations in the southern part of Bhutan. The government adopted ethnic cleansing policies. At the time we were not allowed to worship the Hindu goddess. But my parents kept them secretly and brought them to Nepal. Statues of the goddess are very valuable to my parents. And still my Mum is praying and worshipping to these statues in the belief of getting strength, power and wealth. These are very special to my Mum.

Tika Poudyel was interviewed on 20 December 2012.

Research, interview, research, text edit, and film production by Karlie Hawking, Albury Library Museum

Filming, editing and photography by James Gallimore.

Film transcription by Catherine Phelan.

Web layout by Annette Loudon, NSW Migration Heritage Centre.

This Moving interview is part of a collaborative project between the NSW Migration

Heritage Centre and Albury City.