In the late 19th century Chinese men were employed in land clearing, market gardening and general labouring throughout NSW. The cleared land was used for wheat growing and sheep grazing and the men lived in camps outside towns and on pastoral properties.

Without scrub cutting there would have been far fewer Chinese workers and gardens in NSW. The amount of land cleared was enormous. In 1890 the manager of Coan Downs, a 96,000 hectares property north of Hillston, noted that if it had not been for Chinese labour the station would not have had more cleared land and grazing capacity than any other station in the area1.

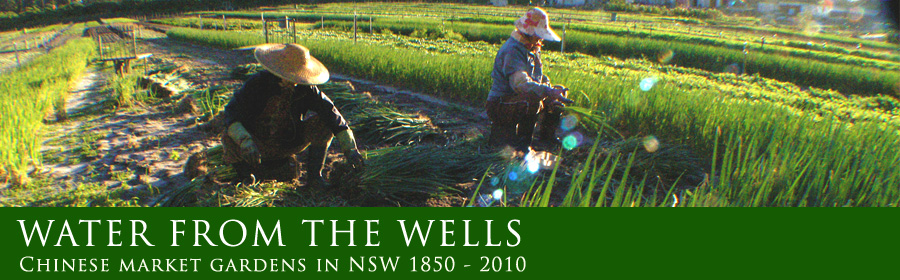

[image title="Chinese market gardens, c.1901" size="full" id="90134" align="none" alt="Chinese market gardens, c.1901. Courtesy Pictures Collection: State Library of Victoria. This is a typical scene of the rural Chinese market garden. Labour intensive and simple." linkto="viewer" ]

All the camps and gardens had the hallmarks of Chinese gardens- harrowed fields, orchards, wells and extensive canal networks. The Chinese market gardeners lived in simple shacks on the gardens made from timber and corrugated iron scrounged from the area. They were usually located on the fringes of European settlement on the outskirts of towns or near large grazing properties that had access to a plentiful water supply. While the Chinese provided fresh vegetables and contributed to the local community they were appreciated but never fully accepted.

One of the earliest accounts of these gardens resulted from the aftermath of a brawl between the Chinese and Europeans in 1895. On the day following Chinese New Year a number of Europeans were drinking on the banks of the Lachlan River at Hillston where 40 Chinese lived. Another Chinese garden was located across the river. The European visitors were welcomed by the Chinese gardeners, but some of the more drunk Europeans began to pull fruit from the trees to provoke a fight. A brawl broke out and about 30 Chinese and 20 Europeans were involved in the melee. One Chinese man was killed and three severely hurt. Ten Europeans stood trial, but were all acquitted of manslaughter.

Despite tensions that often manifested in violence, the Chinese were very highly regarded as market gardeners largely because they were not in direct competition with European workers and provided a cheap and consistent supply of vegetables to towns folk.

The same situation applied to their employment as scrub cutters and land clearers. In 1890a correspondent for the Sydney Morning Herald stated that the Chinese were highly sought after as land clearers. It was not so much because they worked for less, for in many cases they got the same wages or even more than European workers; it was because they were regarded as more reliable. As cooks and gardeners the Chinese were invaluable as they produced nearly all the vegetables grown in the bush.

They could also turn their hand to rabbiting and were found ready to do nearly all the rough work on the stations. In Wagga Wagga the Chinese were renowned for their generous contributions to the hospital and local churches, and events such as the opening of the new ‘joss house’ in 1887 and celebration of the Chinese New Year attracted many Europeans.

In the New England area, Chinese market gardens were established as copper and tin mining activities expanded. Large gardens were established at Inverell and Emmaville. In 1936 two big Chinese market gardens were operating at Inverell employing about 48 men at both.

On the north coast of NSW Chinese agents and wholesalers moved into the area of banana growing. Chinese business men dominated banana marketing in Sydney and Melbourne from the late 1890s. From about 1917 they began buying land in the Tweed and Brunswick valleys to grow bananas, using Chinese labour. They encountered a hostile reception from local growers and World War One soldier settlers who accused them of taking up land that they had a ‘natural’ right to. Newspapers hysterically predicted an alien invasion backed by wealthy Chinese merchants. Such was Australia’s culture under the White Australia policy.

In the 1920s an introduced disease called ‘Bunchy Top’ shut down a lot of NSW banana plantations. At this time most Chinese left the growing side of the industry, but continued to dominate the wholesale marketing sector. The Murwillumbah firm of Chow Kum & Co was the local agent for many banana growers in the early years of the industry.

The Chinese were heavily involved in tobacco growing also. Across NSW tobacco growing was enhanced by Chinese gardeners’ labour and adaptive farming techniques. At Albury, Texas, Bonshaw, Inverell, Tumut, Manilla, Dubbo and Bathurst large numbers of Chinese were employed on tobacco farms from the 1870s to 1920s. Again Chinese market gardens sprung up around these areas as a result.

Despite the early anti Chinese riots on the gold fields, it appears that from the 1860s the racial situation in rural NSW had become more tolerant and accepting. The Chinese were noted for their lawfulness and generosity to the local community, and were an accepted part of everyday life. The Chinese market gardeners and land clearers served an important economic function in opening up the land and were essential to the development of regional NSW.