Becoming Australian

Bonegilla was a 'training centre' where non-British migrants were given courses in English and in the Australian way of life to ease their assimilation.

Language teachers focused on oral work. They used role plays and repetitive rhymes to try to demonstrate common sentence patterns. Classes around Bonegilla could be heard chanting or singing 'One man went to mow'or 'Three blind mice'. Little work was done on vocabulary. That would come later.

Negotiating coins at the canteen, Dawson Photographic Album, 1953, Albury LibraryMuseum.

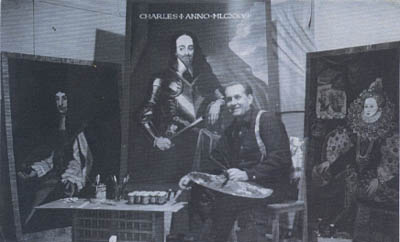

Bonegilla celebrated the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 and the Royal Visit in 1954. Drawing on books about the Wars of the Roses, two migrant employees, Danko Martek and W. Dubrond, completed portraits of early British monarchs, heraldry banners and shields for a mock Tudor setting in a recreation building dubbed 'Tudor Hall'. Migrants might be expected to become acquainted with the history and heritage of a British-Australia.

At Bonegilla the policy of assimilation was interpreted as helping the migrants 'to take their place in the community'. Colonel Henry Guinn, Director of the Centre from 1954 to 1964, encouraged engagement with the local community through competitive sports, concerts, handicraft and cooking displays. Assimilation, he thought, involved building acquaintance and friendships between people of all nationalities and between hosts and newcomers. He thanked CWA groups who arranged visits for giving migrant women 'the confidence to mix with Australians'.

Becoming Australian meant merging into the wider society. Successful migrants would learn and use only English. On festive occasions they might parade colourful aspects of their European heritage, but assimilation meant they and their children would blend into the community.

Arthur Calwell visited Bonegilla frequently when he was Minister for Immigration, Albury LibraryMuseum.

Safely isolated on the southern bank of Lake Hume, 12km from Wodonga in North-East Victoria and over 300km from Melbourne and 600km from Sydney, Bonegilla warranted no attention from the metropolitan dailies while it ran quietly and efficiently. It did, however, concentrate the attention of the press on three occasions.

In 1949 thirteen newly-arrived children died from malnutrition in the winter of 1949. There was a flurry of activity to explain that all was well at Bonegilla. An inquiry found that children suffering from gastroenteritis had been on a ship-board diet of boiled water for a prolonged time. The inquiry was also critical of how the Bonegilla hospital was under-staffed and inadequately equipped.

Young Italian migrants protested about the lack of work in 1952. They also complained about the food they were served, the lack of heating and the paucity of the recreation facilities at Bonegilla. Their protests hurried along renovation of the huts and spurred changes to ensure food better matched national tastes.

In 1961 German and Italian migrants posted 'ugly signs' along the road to the Centre: 'We want work or back to Europe'; 'Bonegilla camp without hope'.10 They smashed the employment office and clashed with police. Both incidents embarrassed the government into reviewing its intake and settlement policies. A few years later Bonegilla was deemed obsolete and redundant. The last arrivals came in November 1971. The Reception Centre closed at the end of the year without much public notice.