Finding Jobs

A hot meal awaits newly arrived Dutch migrants after disembarkation from the train at 10pm, 1955, National Archives of Australia A12111, 55/22/78.

Beyond settling into the Reception Centre huts and routines, there were the more pressing challenges of finding work, learning a new language, looking out for accommodation outside the Centre and establishing social networks.Migrants agreed to work as directed in return for their passage. At selection they were asked 'Are you prepared to take any kind of work?'. They signed contracts that specified that those over 16 years-old would work as directed for two years. As employment often depended on language fluency they agreed to 'use every endeavour to learn the English language'.

At Bonegilla employment officers assessed suitability and dispatched workers to jobs where they were needed Australia-wide. The migrants' wishes 'were taken into account', but repeated refusals of offers of work could lead to loss of social service benefits.

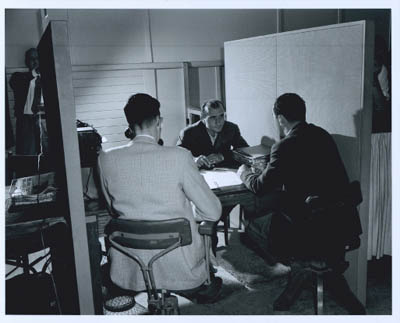

Employment officer and interpreter with interviewee, National Archives of Australia A12111, 55/22/83.

The physical isolation of Bonegilla and living conditions at the Centre may have strengthened the pressure on migrants to take up employment offers.Many resented the ways in which their professional or trade qualifications were ignored. They were expected to start as labourers or domestics. However, they did receive award wages.

Mostly they talked about their jobs, who was being sent where to work … how much one had to work to buy a block of land and build a shack on it, Dmytro Chub, Ukraine, 1949.

At any one time there could be over 400 migrants employed at Bonegilla in a variety of staff occupations. Such employment was always a good option. Public Service conditions applied. Accommodation costs were low. The job was known and less risky than a job elsewhere. Married couples with two jobs at the Centre could avoid separation. Staff were housed in more comfortable staff blocks. They had access to a staff club building, a flood-lit tennis court and a bowling green. In return for privilege they were required to attend English classes and gain certificates of proficiency.

Many migrant staff lived and worked at Bonegilla for years. They generally became Bonegilla champions and still remember the achievements of the Centre with pride. They counter criticisms of it as a bleak camp of no hope, somehow akin to modern-day Detention Centres. Memories of the long-term residents 'were deep and often affectionate'.