From the 1850s German settlers escaping the rising nationalist sentiment in Germany began arriving in the Australian colonies looking to start a new life. Port Adelaide was the point of arrival for the majority of German settlers. The Germans moved onto Western Australia, the Barossa Valley, the Riverina and South East Queensland where they found the regions suitable for wheat and dairy farming, the planting of vineyards and wine making. They formed close communities transforming the dry marginal environment into good farming land. The German Australians maintained strong cultural ties with their German heritage up until World War One.

Christening Font from Bethlehem Lutheran Church Jindera NSW, c.1872. Courtesy of the Museum of the Riverina

By 1914 over 100,000 Germans lived in Australia and they were a well established and liked community. With the rising tension between the British and German Empires this began to change and German Australian communities often found themselves the subject of suspicion and animosity. When war broke out in 1914 this changed to outright hostility. In 1914 Australia was besotted with war fever and people were keen for ways to get involved to ‘do their bit’.

The sinking of the German light Cruiser SMS Emden by the Australian light cruiser HMAS Sydney in the Cocos Islands was one of Australia’s first actions of the war and it excited the nation. The event created hysteria about possible German naval attack thus establishing immediately the cultural and national divisions within the community.

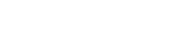

In 1915, Germans and Austrians who were old enough to join the army were put into German Concentration Camps across the continent. In New South Wales the three main internment camps were at Trial Bay Gaol, Berrima Gaol and Holsworthy Army Barracks. Women and children of German and Austrian descent, detained by the British in Asia, were interned at Molonglo. Others were carefully watched by the police and neighbours. Germans lost their jobs or had their business destroyed. Some voluntarily went into camps so their wives and children could survive on a government allowance.

In other changes that affected Germans living in Australia their:

- schools and churches were closed

- music was banned

- food was renamed

- place names (42) were changed to British ones – Blumberg became Birdwood & German Creek became Empire Bay

- traders, businessmen, sailors and tea planters in South East Asia were arrested and transported to Australia to be interned in the camps.

(The Australian Government sought to…) destroy the (German) community as an autonomous, socio-cultural entity within Australian society…. through many different avenues, the closing of German clubs and Lutheran schools, the internment of the leaders, so as to deprive German-Australians of their spokesmen, their representatives in the mainstream public sphere of Australian society. Together with the destruction of what might be called the socio-cultural infrastructure of the community, this would have the effect – it was thought – of intimidating and keeping in check the rest of the community: it would lead to its disintegration and eventual disappearance. Prof Gerhard Fischer history; Internment at Trial Bay during World War One, MHC:PHM, 2005, p.30.

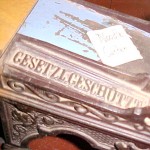

Anti German sentiments intensified in Australia after the Battle of the Ypres, Passchendaele and Pozieres saw significant Australian casualties in France and Belgium. Nationalism was rising as the main reaction to the war on the home front. Nationalistic propaganda posters and newsreels were created demonising the German community. Nationalistic and anti- German propaganda was rampant in the Prime Minister Billy Hughes’ push for conscription.

A German pill-box at Ypres France, a place that saw large Australian casualties. Pill-boxes were built of concrete with sides 1 – 2 metres thick to allow soldiers to endure bombardments. Photograph Capt. F. Hurley, August 1917- August 1918. Courtesy State Library of New South Wales.

During World War One four out of every ten Australian men aged 18 – 45 enlisted. Gallipoli was just the introduction to the newly formed Australian Imperial Forces (AIF) of the realities of industrial mechanised war. After Gallipoli came the horror of France and Belgium. Battles at Passchendaele and Ypres waged a heavy casualty toll on a generation of young men from all over Australia. Out of a Australia’s population of 2 million, 59,000 men were killed and 176,000 were wounded. This toll manifested itself in the growing ‘Roll of Honour’ monuments that mushroomed through out the cities and regional Australia from 1919 onwards.

Arthur and Alice Hucker preparing to attend the Mackay Anzac Day ceremony in memory of their only child, Private Albert Hucker. C.1920. Courtesy Australian War Memorial

Case Study: Albert Hucker was 22 when he enlisted in the AIF and embarked for training in England in 1916. He was transferred to France in November 1916 where he received severe bullet wounds to his right arm in battle and was hospitalised. He returned to the front in France in 1917 where he was killed in a bombardment at Thames Wood at the First Battle of Passchendaele in Belgium on the 30th of October 1917. He was one of four men in his company killed by the same shell. A letter from his friend to his mother said he had been buried, but the AIF couldn’t find his grave. It was destroyed soon after the burial by the continuing battle. Hucker has no known grave and is commemorated on the Menin Gate. His parents attended Anzac Day ceremonies every year until their deaths after the World War Two. This was a common experience for families across the nation and fed the anti German sentiments at home.

By 1916 fewer men were volunteering for the army. The war was taking longer than people had expected and many thousands of soldiers had been killed. Prime Minister Billy Hughes wanted to introduce compulsory military service or ‘conscription’ to maintain the supply of solders required reinforce the AIF. Australians had to make an important decision as Billy Hughes decided to put the question to a referendum in October 1916. Hughes led the Australian Labor Party and most of its members did not support conscription. One way Hughes and the pro – conscription lobby sought to sway voters was to create a visual target to blame for wartime losses and pain. Hughes turned the Australian German community into scapegoats for his conscription cause. In the conscription debates of 1916 and 1917 Hughes conducted a campaign of rumour mongering, harassment, persecution and the creation of a large internment camp on the outskirts of Sydney at Holsworthy Army base at Liverpool. Hughes was defeated but it was a close result.

Claude Marquet, “I’ll have you!” An anti conscription cartoon, Australian Worker, 13 December 1917, p.9. Newspaper Collection, Courtesy State Library of Victoria. Anti conscription campaigns tried to use the same tools as Hughes did in vilifying the Australian German community. Here Hughes is depicted as a monster. The suspicion of anything not deemed ‘normal’ is a persistent feature of Australian culture.

Case Study: Many sons and grandsons of German migrants joined the AIF and went to fight for Australia on the Western Front. Many, such as Tumbarumba’s George and Herbert Heinecke died in France. George and Henry’s father George senior, despite having lost two sons in the war, was constantly harassed because of his family’s German heritage. In a letter to the Tumbarumba Times in August 1918 he wrote, “I already have 17 [relatives at the front], including two sons who were killed, and one sister’s son also killed, and another sister’s son a prisoner of war in Germany; my wife’s brother’s three sons, two dead and one wounded”.

In 1917, when German submarines began to attack American cargo and passenger ships, the United States entered the war, committing over one million soldiers to the war in Europe. A socialist revolution in Russia deposed the old government, and led to a pull-out of Russian troops and a treaty with Germany. Germany’s allies, Austria-Hungary and Turkey, were severely weakened by the war and had to withdraw. Without support, and in the face of a fresh army from the United States, Germany had to accept defeat. In November 1918, fighting stopped and an Armistice was signed. The world would never be the same again.

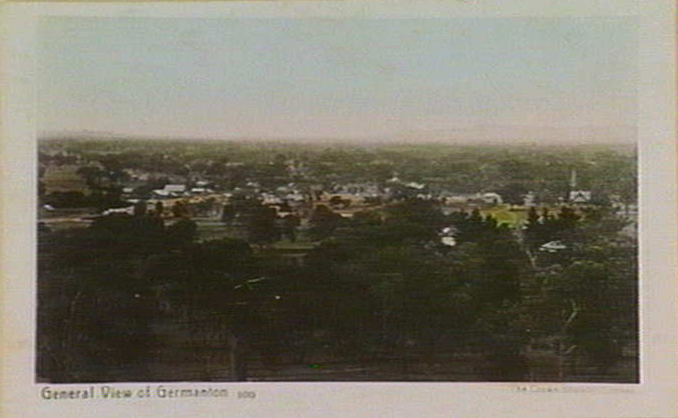

Meanwhile throughout Australia many German families changed their names to stop harassment from the government and a war mad community, German schools and churches were closed, German music was banned, German food was renamed, German place names were changed to British ones (in South Australia under the Nomenclature Act) — Blumberg became Birdwood, Germanton became Holbrook & German Creek became Empire Bay.

General View of Germanton, c.1910, State Library of Victoria

During World War One the NSW government changed the name Germanton to Holbrook amid anti German hysteria. The town was originally called Ten Mile Creek in 1836. A German migrant, John Pabst, became the publican of the Woolpack Hotel in 1840 and the area became known as ‘the Germans’. By 1858 the name had evolved in to the official name of Germanton. In 1876 the name Germanton was officially gazetted. On 24 August 1915 the town was renamed Holbrook in honour of Lt. Norman Douglas Holbrook, a decorated wartime submarine captain and winner of the Victoria Cross. Lt. Holbrook commanded the submarine HMS B11.

During the campaign for the Conscription Referendum the large German community in the Riverina were selected for special attention. To some it seemed that people of German origin were to blame for the lack of success of the first conscription referendum in 1916. After the failure of the second Conscription Referendum in 1917 the anti-German campaign was increased further. People of German descent were stopped from joining the Army, holding civil positions such as local councillors or Justices of the Peace.

In March 1918 Australian secret service officers were sent to Jindera and Walla Walla to spy on the Community. Four Australian men of German decent, Hermann Paech, John Wenke, Edward Heppner and Ernest Wenke were arrested for unspecified un-Australian activities and delivered into the custody of military police, who took them to Holsworthy Concentration Camp.

The secret service officers reported that ‘the use of the German language has thoroughly Germanised the bulk of the population of the Riverina which would otherwise have become gradually Anglicised as each generation grew up’.

The outbreak of war was greeted in Tasmania with enthusiastic expressions of loyalty to the British Empire. Enemy aliens were quickly identified usually by German or foreign heritage and speculation. An internment camp established at Claremont then moved to Bruny Island. The town of Bismarck was renamed Collinsvale, and many Tasmanians of German descent, the largest non-British national group in the population, were persecuted. In one case Gustav Weindorfer was accused of being a German spy and using his chalet at Cradle Mountain as a radio station to contact German ships. He was expelled from the Ulverstone Club and his dog was poisoned.

In Western Australia the German community were immediately placed under surveillance on the outbreak of war. Prominent members of the German Community were investigated. Karl Fink, the owner of Fink’s Hotel, the largest in Perth, fled to Sweden and his hotel was confiscated by the Public Trustee.

In Broome, Western Australia Toni Ulbrich worked on a pearling vessel. As all enemy aliens on neutral ships had to be interned he was arrested in 1916 in order to ‘secure the public safety and the defence of the Commonwealth. Ulbrich was sent to Holsworthy where he remained until 1918.

German business and individuals were under constant scrutiny. The Alhambra Café, Schruth’s Beaufort Arms Hotel and Mrs Carlshausen’s Wine Saloon in Beaufort St Perth, Western Australia were under surveillance. It was reported that the wine saloon was ‘frequented by a number of Alien Enemies and Naturalized Aliens amongst are a large percentage who are disloyal’.

A Health Inspector in Geraldton, Western Australia claimed in a memo that there was a fleet of sea going yachts owned by Germans that appeared to be on fishing trips and often disappeared for weeks and were capable of carrying wireless equipment.

‘British’ trade unions, business and the Western Australian State Government took advantage of the situation. Reports by informers were never ending and suspicion was everywhere. Austrian, Croatian and Italian miners were sacked and run out of town in the Kalgoorlie Mines on demands from the mining trade unions.

The New Guard conservatives saw the war as an opportunity to get at their old rivals the Communists and maintain the ‘Britishness’ of Australia through the War Precautions Act of 1914. Business leaders had Communist Party members listed as unpatriotic enemy sympathisers and interned with the assistance of compliant State and Commonwealth Governments. The communists had opposed the war and nationalism maintaining that workers would kill other workers in the interest of capitalism, which largely proved to be correct.

For home front Australia the Great War became a blur of the many themes that had dominated nineteenth century Australian life- the working mans paradise vs. free trade and capitalism, the aspiration of a British Australia and a undying loyalty to the concept of the British Empire. However for German Australia it meant sustained scrutiny, suspicion and persecution that eventually erased nearly all traces of the Australian- German community from the cultural landscape in a hysteric ethnic purge. Many families continued to Anglicise their names. At Temora there is evidence of at least one local ‘German’ family changing their name by deed poll. Many other families clandestinely changed the spelling of their names.

What remains are places and objects whose heritage is nearly forgotten. Many families are aware of a German presence in their history, but the stigma of World War One and Two has erased almost all traces of it from many families’ and community memory.