The outbreak of fighting in Europe in August 1914 immediately brought Australia into the Great War. Within one week of the declaration of war, all German subjects in Australia were declared ‘enemy aliens’ and were required to report to the Government and notify their address. In February 1915 the meaning of ‘enemy aliens’ changed. It came to include naturalised migrants as well as Australian born persons whose fathers or grandfathers had been born in Germany or Austria. Since it was impossible to intern all enemy aliens resident in Australia, the Government pursued a policy of selective internment. They targeted the leaders of the German Australian community — including honorary consuls and pastors of the Lutheran Church, businessmen and the destitute. Some internees had been accused of being disloyal by neighbours or had come to the attention of the police by accident. Internment in Australia was regulated by the War Precautions Act 1914 and internees could be held without trial.

Internment Camps were established at Rottnest Island in Western Australia, Torrens Island in South Australia, Enoggera in Queensland, Langwarrin in Victoria and Bruny Island in Tasmania.

In New South Wales the main internment camp was at the Holsworthy Military Camp where between 5000 and 6000 men were detained. Women and children of German and Austrian descent, detained by the British in Asia, were interned at Bourke and later Molonglo near Canberra. Former gaols were also used, with men interned at Trial Bay Gaol and Berrima Gaol.

In 1915 the Commonwealth Government decided to centralise the internment camps in New South Wales and internees from the other States were transferred to the Holsworthy Internment Camp.

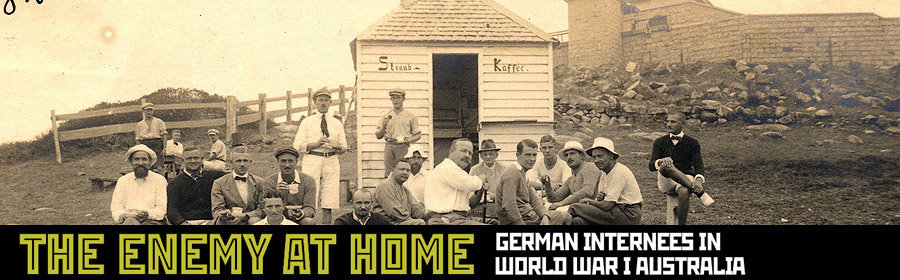

Life in the camps was varied. Trial Bay was an elite camp and had the most privileges, Berrima was a camp for navy and merchant officers who led a regimented and self regulated life. Holsworthy was the most like a prison camp of all the camps. Internees at all the camps formed management committees, theatre and arts groups, self education classes, restaurants and cafes. There were strikes and riots over conditions at Trial Bay and Holsworthy where the camp commandants quickly negotiated outcomes.

One of the most difficult problems of camp life for internees was sexual frustration, resulting from being confined in an all male environment for years on end. The enforced celibacy led to a number of psychological problems. Many internees experienced the symptoms of depression and anxiety disorders. Dr Max Hertz, one of the prominent internees at Trial Bay, who was also camp doctor and an internationally renowned orthopaedic surgeon from Sydney, reported on ‘self abuse’ and the ‘ugly side’ of the sexual question.

The Australian Government was very serious in sending a message back to Germany that the internees were well looked after so that Australian prisoners of war in Germany received the same treatment from their German captors. Like most wars, despite the propaganda portraying each other as monsters, when communities meet each other they realise they have more in common than not.