BRITAIN’S MOVE INTO THE PACIFIC

Black-eyed Sue and Sweet Poll of Plymouth taking leave of their lovers who are going to Botany Bay, Robert Sayer, 1792. Courtesy National Library of Australia

By the 1790s British Investors were purchasing 38,000 slaves a year. Over sixty percent of the world’s slave trade was transported in British ships. Slavery and the feudal farm system were under attack by evangelical reformers who fought for personal liberty and the right of the individual. Industrials too had become opposed to slavery and the feudal farm system for they had discovered that for manufacturers, it was not economical to rely on a captive work force who along with their families, had to be fed, clothed and housed on a daily basis. Profits could be maximised by employing free mobile labour, paid a cash wage based not on the labourers and their families needs but on how long they actually spent on the job operating the machine or tending the flock.

These ‘reforms’ only worked to create the massive unemployment of the Industrial Revolution. Food and materials that was once supplied from farms across the British Isles were now replaced by imports that were processed in mills and factories. British farm owners turned their land over to sheep grazing. They ‘enclosed’ their land evicting farm labourers and their families, who, with no jobs and nowhere to live locally, flocked to the cities looking for work in the mills. Jobs were scarce and soon a petty criminal underclass had developed.

Poverty, social injustice, child labour, urban filth, unhealthy living conditions and long working hours were widespread in 18th and 19th century industrial Britain. In 1833 and 1844 the first Factory Acts restricting child labour were passed in Britain.

The population of England, remained steady at 6 million from 1700 to 1740, but rose noticeably after 1740. By the time of the American Revolution, London was overcrowded with the unemployed and flooded with cheap gin. Crime had become a major problem.

In 1784 a French observer noted that from sunset to dawn the environs of London became the patrimony of brigands for twenty miles around.

Britain did not have a police force as we know it. Virtually all criminals were caught by informers or denounced to the local court by their victims. This created an environment for false accusations and the use of courts to settle petty disputes, thus an inherently unjust system.

By the 1770s the Bloody Code meant there were 222 crimes that carried the death penalty. Almost all of them were crimes against property. Many included offences such as the stealing of property worth over 5 shillings, the cutting down of a tree, stealing an animal or poaching from an estate. Public executions became a popular form of entertainment. Michael Hammond and his sister aged 7 and 11 years old were hanged at King’s Lynn in 1708 for petty theft. The Bloody Code lost favour in the 19th century because legal practitioners and middle class liberals thought that the punishments were too harsh.

The jails were so overcrowded that hulks left over from the Seven Years War were used as makeshift floating prisons around the waterways of Britain. The British Government was under pressure to do something to alleviate the escalating crime and empty the jails and hulks.

The Government wanted punishments to deter crime, but also wanted them to be more humane so the transportation for the term of your natural life became the more common sentence from the 17th century to the 19th century. Around 60,000 convicts were transported to the British colonies in North America in the 17th and 18th centuries.

When the American Revolution brought an end to that means of disposal in 1776, the British Government was forced to look elsewhere.

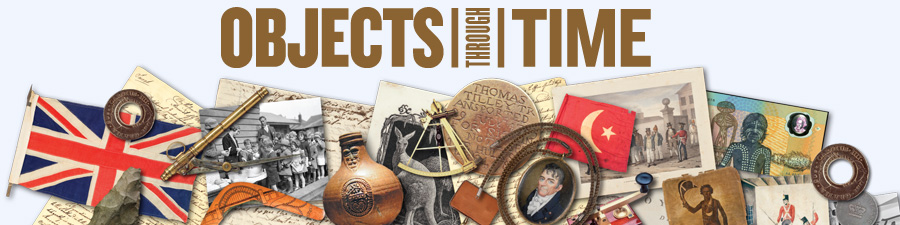

After Captain James Cook’s famous voyage on HMS Endeavour to the South Pacific where he claimed the east coast Australia for Britain, the British Government became more interested in the existence of the continent of Australia. Joseph Banks, an influential naturalist on Cook’s expedition and a wealthy merchant, convinced the British Government that breadfruit from Tahiti was an ideal crop to grow in the West Indies to feed slaves. Banks also argued that Botany Bay would make an ideal British port in the Pacific and that a settlement should be established with indentured convict labour. A penal settlement was seen as a possible solution to the increasing problem of petty crime and the crisis of overcrowded prisons in English cities.

Despite it being a huge and very expensive experiment to set up a colony in an unknown land on the other side of the world, Britain decided to establish a penal colony at Botany Bay under the leadership of Captain Arthur Phillip.

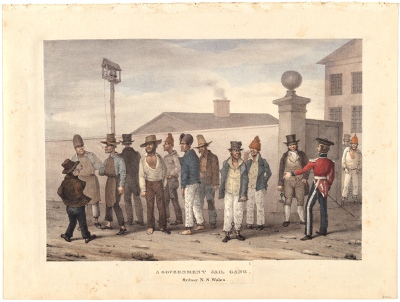

The system of using convict labour to build the colony would be called the ‘Government System’.