Era: 1840 - 1900 Cultural background: Chinese, English Collection: Mitchell Library, State Library NSW Theme:Gold Government Immigration Restiction Labour Movement Miners Riots Settlement

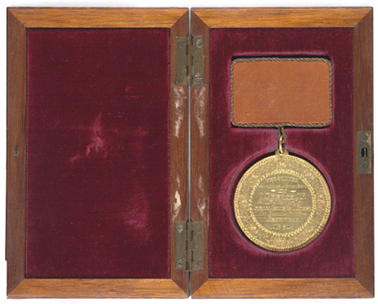

De Boos Medal, 1881. Face and reverse. Courtesy of the State library of New South Wales

Collection

State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

Object Name

De Boos Gold Medal.

Object/Collection Description

A gold medal attached to silk ribbon, inside velvet-lined wooden box. This medal was presented as a mark of esteem to C. De Boos, J.P., Gold Fields Warden from Chinese Miners in the district of Braidwood, 1881. The reverse is inscribed in Chinese characters. ‘In 1874 [De Boos] was appointed a police magistrate and mining warden…The Chinese miners in the Braidwood district subscribed a piece of gold each, from which was designed and presented to him, a Chinese medal. Armed with this “passport” it would have been possible for him to have travelled all over China without molestation.’ Dimensions: 50 mm diameter, box 153 mm x 95 mm x 25 mm.

De Boos Medal, 1881. Courtesy of the State library of New South Wales

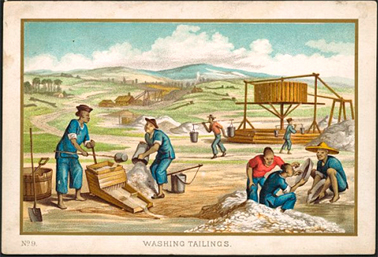

The discovery of gold in New South Wales from the early 1850s saw a huge influx of migrants in search of instant wealth. The primary result of the Gold Rush was that the economy boomed and, for a short time, gold outstripped wool as the Colony’s primary export. Many of the people who came in search of gold were Chinese men. Drawn from their home villages (mainly in Kwangtung) by the first gold rushes in Victoria, California and New South Wales in the 1850s, they usually arrived in organised groups of 30 to 100 men. In 1861 there were about 13,000 Chinese in New South Wales with the majority (12,200) on the goldfields. Throughout the 19th century, Chinese arrivals continued to the mining regions of New South Wales, replacing those who had returned home or left for opportunities elsewhere.

The Chinese diggers moved from goldfield to goldfield within New South Wales and across the border. Constantly on the move, their presence and experience are evidenced mainly from the observations and interpretation of Anglo-Australians, from archaeological digs and from objects saved by families and community members. There are few written accounts and sources from a Chinese perspective. The object is a rare one providing a Chinese perspective on life on the goldfields. The Chinese attracted particular attention and local newspapers were quick to comment on their distinctive features, clothes, languages and habits – especially their tendency to travel en masse – their methods of transport, their diligence, tirelessness and productivity. Any admiration of their work ethic was offset by envy and resentment when times got hard. The Chinese were often scapegoated by disgruntled Anglo diggers as seen in the violent anti-Chinese riots at Turon (1853), Meroo (1854) Rocky River (1856) Tambaroora (1858) Lambing Flat, Kiandra and Nundle (1860 and 1861) and Tingha tin fields (1870). They were seen initially as oddities, later as rivals and then as threats to white Australia.

Washing Tailings, Ten Australian Views, C.1870s. Courtesy National Library of Australia

Charles De boos a journalist and police magistrate, was born on 24 May 1819 in London, son of Henry Charles de Boos and reputedly grandson of a French count. After education at Addiscombe, Surrey, he went to Spain as a volunteer in the Carlist war. He arrived in Sydney in 1839 and took up land on the Hunter River. Unsuccessful on the land, he became a journalist first on the Monitor, then the Sydney Gazette. In 1851 he went to Melbourne and was commissioned by the Argus to report on the Victorian goldfields. He spent five months at Ballarat, Forest Creek and Bendigo, and in 1853 went to the Ovens on a similar mission. In 1854 he became a shorthand writer in the Victorian Legislative Council. In 1856 de Boos returned to Sydney and joined the Sydney Morning Herald. In the first parliamentary recess he visited the New South Wales goldfields and as the Herald’s special correspondent later reported on all the newly-discovered fields. The knowledge he acquired of mining, its laws and the needs of miners was later to benefit him. In 1862 he created the countryman, ‘Mr John Smith’, who described the doings of parliament and the politicians in a primitive form of ‘Strine’. ‘John Smith’ was resurrected in the Sydney Mail and Herald during the Duke of Edinburgh’s visit in 1868, and again in 1870 after a tense election. The Congewoi Correspondence, letters of Mr. John Smith edited by Mr. Chas De Boos, was published in 1874. The most enduring work of de Boos was as the Herald’s parliamentary reporter. After a century his weekly column, The Collective Wisdom of New South Wales in 1867-71, still brings to life a host of politicians and well-known figures, for his quick ear caught many exchanges omitted in the official reports. In 1867 de Boos published, first as a serial, Fifty Years Ago: An Australian Tale and dedicated it to John Fairfax. A revised edition appeared in 1906 as Settler and Savage. In 1871 his Random Notes by a Wandering Reporter recorded his impressions of New South Wales.

De Boos’ evidence before the 1870 royal commission on the goldfields led to his appointment in January 1875 as mining warden of the Southern Tumut and Adelong mining districts. In May 1875 he was appointed magistrate to interpret the mining acts and maintain law and order. In December 1879 he became warden for the Lachlan and in August 1880 for the Hunter and Macleay mining districts; he was also appointed police magistrate and coroner at Copeland. In 1881-82 at Temora, de Boos was accused of partiality, insobriety and improper language. Three times in the Legislative Assembly in 1882 William Forster asked questions about his conduct and was told by the minister of justice that he had been reprimanded, although some of the complaints had not been substantiated. De Boos ceased to be a mining warden in July 1883 but remained police magistrate at Copeland until he retired on 15 June 1889. An obituarist claimed that he had more than justified his appointment as a mining warden and in 1881 had been presented with a gold medal ‘as a mark of esteem’ by Chinese miners in the Braidwood district. In retirement de Boos published several short stories.

Despite anti Chinese legislation and ill feeling in sections of the community the law dealt with all nationalities fairly as evidenced by the presentation of the medal by the Chinese miners. This evidence highlights the fact that despite the ever prevalent anti Chinese attitudes assaults against Chinese were dealt with by the courts, with the magistrates and the press often reminding the community that regardless of what they may think of the Chinese as a race, as individuals they were entitled to the same legal protection and penalties as everyone else.1

De Boos is remembered in parts of southern New South Wales in place names such as De Boos St in Temora.

The medal’s historic value lies in its relationship to the themes of the gold rush experience, racial antagonism, the fear of the exotic and unknown, and ideologies that fostered Australia’s links to Britain and the development of racially discriminative Colonial policies culminating in the first act of the newly Federated Commonwealth of Australia, the Immigration Restriction Act 1901. Despite these dominant themes in Australian history sometimes the realities in the communities reflect friendship and respect that inevitably develops among different cultural groups.

The medal has aesthetic significance in the design, language and the manufacture of a late Victorian medal and its ribbon and case.

The medal provides a research tool for historians to explore the culture and politics of the Europeans and Chinese on the goldfields. Objects such as the medal have already provided invaluable evidence in exploring the experiences and world of the Chinese communities in 19th century regional New South Wales. The medal is evidence of the even handedness employed by some Europeans despite wide ranging suspicions of the closed culture of the Chinese on the goldfields. The myths created about the economic competition of the Chinese on the diggings were to form the basis of hysterical racial slurs against the Chinese in order to drive them off of the diggings. These myths later provided the basis for the racist logic of the Immigration Restriction Act 1901. Some Europeans with an observant journalist’s eye such as De Boos noted the Chinese diligence, efficiency and frugal lifestyle instead.

The Chinese who reside in regional New South Wales are predominately descended from the early migrants to the goldfields. Objects such as the medal provide a means for these communities to recognise and acknowledge the violence and racism dished out to their ancestors, but also the friendships and acts of equality as symbolised in the Medal. By 1881 the racial situation on the southern and western New South Wales rural districts had become more tolerant and accepting. Objects and collections from Chinese communities provide the material culture for the stories of ancestors. These objects and collections have a resonance across regional New South Wales and Australia.

The medal is well provenanced. It was in the collection of the De Boos family from 1881 and was presented to the State Library of New South Wales in 1928.

The medal is rare because it was made for a specific purpose and event. The medal is rare also because it alludes to contradictions to the omnipresent anti-Chinese attitudes in late nineteenth century Australia that manifested themselves in the Lambing Flat riots and racists colonial legislation.

The medal represents the experience of the 19th century Chinese on the goldfields. The myths surrounding the Chinese created largely on the goldfields provided the seeds for the ideology for the Immigration Restriction Act 1901. The medal represents the formation of a community of Chinese miners who held the warden in high esteem for supporting their rights and interests.

The condition of the object is good given the rarity and fragile nature of the fabric.

The medal is a powerful interpretive tool in communicating the experience and the treatment of the Chinese on the diggings and the evidence of attempts by Goldfields wardens to apply an even hand in interpreting the mining acts. It also provides evidence on the history of the relationship between China and the West in general.

Footnotes

Bibliography

Coupe, S. & Andrews, M. Their Ghosts may be heard: Australia to 1900, Longman Cheshire, Sydney, 1992.

Regional Histories of NSW, Heritage Office & Dept of Urban Affairs & Planning, Sydney, 1996.

Significance: A guide to assessing the significance of cultural heritage objects and collections, Heritage Collections Council. 2001.

Wilton, Janice, Golden Threads: The Chinese in Regional NSW, 1850 – 1950, New England Regional Museum & Powerhouse Publishing, 2004

June 2007

Migration Heritage Centre

Crown copyright 2007©

The Migration Heritage Centre at the Powerhouse Museum is a NSW Government initiative supported by the Community Relations Commission.

www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au

Regional Services at the Powerhouse Museum is supported by Movable Heritage, NSW funding from the NSW Ministry for the Arts.

State Library of NSW

www.sl.nsw.gov.au