Era: 1918 - 1939 Cultural background: English, French, German, Jewish, Russian Collection: Powerhouse Museum Theme:Government Labour Movement Riots Settlement

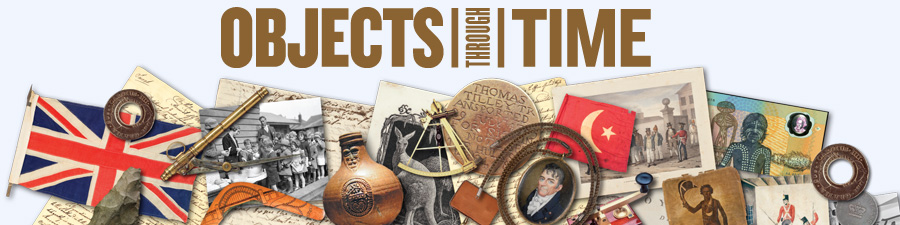

Starvation Debenture, 1932. Courtesy Powerhouse Museum

Collection

Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, Australia.

Object Name

Starvation Debenture Certificate.

Object/Collection Description

Certificate, Starvation debenture, paper, rectangular, horizontal format, off-white with green and black print, in form of debenture or stock certificate. Printed at bottom of reverse side: ‘Authorised by United Country Bureau of Publicity, Information & Research/Printed by W C Penfold & Co. Ltd. 88 Pitt Street, Sydney’. Dimensions: Height 130mm wide X 202mm long.

By 1929 the world economy began to slow. Rural product prices were falling and farmers found it hard to sell their produce overseas. In the cities, businesses found it harder to sell their goods overseas. As production slowed, workers were laid off and unemployment hit 10%. For migrants and soldier settlers already experiencing hard times, this made things worse. In 1929, the economy stalled in what is called the ‘Great Depression’.

The Great Depression started in the United States. In the 1920s, the US economy was booming and lots of people invested all of their savings in shares on the stock market. A lot of investors made fortunes, but in 1929 investors panicked and began selling their shares in mass hysteria. As a large number of shares were sold, share prices plummeted. As the share price fell more people panicked which set up a self-sustaining cycle. On 24 October 1929, the stock market crashed and shares became worthless. This event impacted on countries all over the world.

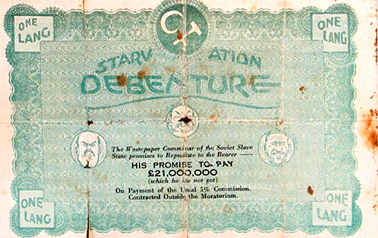

In the 1920s, the United States and Britain were the world’s largest investors in overseas projects. By 1930, the United States stopped investing in other countries, demanded that other countries repay loans owed to it, put up high tariffs on imports and cut back on imports. Britain owed the United States a fortune in loans and called on Australia to pay back the millions of pounds it had borrowed from it in the 1920s. But Australia had no money either. As people lost their jobs, they could not afford to buy goods or pay taxes. It was mainly the unskilled workers and their families that were hit hardest and this included the recently arrived migrant families who were already finding the going tough. Shanty towns sprang up at Blacktown, Sans Souci and La Perouse.

Happy Valley unemployed camp, La Perouse. C.1932. Courtesy State Library of New South Wales

People vowed this would never happen again and the Australian Government took over social welfare in the 1930s.

Children line up for a free issue of soup and bread during the Depression c.1932. Courtesy State Library of New South Wales

By 1931 it seemed that capitalism had – as an economic system failed. The Establishment responded to the Depression with plans for ‘austerity’. In 1930 Sir Otto Niemeyer from the Bank of England visited Australia to advise governments to implement a deflationary policy. Niemeyer contended that wages must be cut to make our exports more competitive and to raise profits. According to Niemeyer living standards were artificially high and trade was the secret to an economic recovery. Niemeyer advised savage cuts in all existing social services. But more significantly Niemeyer demanded that Australia not default on its international loan obligations to Britain. With pressure tactics and careful diplomacy Niemeyer sold his plan to Australian state and federal politicians. They called it the Melbourne Agreement of August 1930.

In the 1930 New South Wales elections Jack Lang was returned overwhelmingly as Premier of New South Wales. His first government (1925-1927) had introduced comprehensive systems of widow’s pensions, child endowment, and worker’s compensation; his second government pledged itself to maintain these hard-won games and steer the state out of the Depression.

Immediately, Lang rejected the Niemeyer plan. At a stormy mass-meeting in the Sydney suburb of Paddington he declared:

… The same people who conscripted our sons and laid them in Flanders’ fields… Now demand more blood, the interest on their lives… 1

The meeting ended in a mass clamour for the principle of Australian Nationalism – Australia First!

Lang proclaimed his plan to fight the Depression:

- reduction of interest on all government debts to Australians

- suspension of all loan payments to all overseas creditors

- the expansion of public works programmes

- bank funding of government works through controlled credit expansion

- reduce immigration and maintenance of the White Australian policy.

Conservatives immediately equated the Lang’s Australia First! Plan with European communism, condemned his nationalism as “anti-British” and mobilised a militia called the New Guard against him. This vigilantism was fuelled by international political tensions stemming from the Russian Civil War.

The Russian Civil War was a multi-faction war that occurred within the former Russian Empire after the Russian provisional government collapsed and the Bolshevik party assumed power in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) in 1917. The principal fighting occurred between the Bolshevik Red Army, often in temporary alliance with other leftist pro-revolutionary groups, and the forces of the White Army, the loosely-allied anti-Bolshevik forces. Many foreign armies warred against the Red Army, notably the Allied Forces, yet many volunteer foreigners fought in both sides of the Russian Civil War. Other nationalist and regional political groups also participated in the war, including the Ukrainian nationalist Green Army, the Ukrainian anarchist Black Army and Black Guards, and warlords such as Ungern von Sternberg.

The most intense fighting took place from 1918 to 1920. Major military operations ended on October 25, 1922 when the Red Army occupied Vladivostok, previously held by the White Forces of the Provisional Priamur Government.

According to Colonel Eric Campbell, founder of the New Guard, his movement was pledged to uphold law and the constitution. By the close of 1931 the New Guard had received 87,000 applications for membership in New South Wales and had built strong links with similar groups in other states. Its strongest support lay with ex-soldiers and ex-officers. His main aim was to crush communism in Australia. The New Guard flourished in an age noted for its confusing attitudes towards patriotism and nationalism, when Australia feared that protection by the Mother Country Britain was preferable to any alternative notion of political nationalism to support Australia’s interests. Lang’s Australian First! Plan was anathema to the officer and commercial classes; the ordinary ex-soldier became the bully-boy of those whose class snobbery was as much directed towards the poor veteran as the city working class.

The New Guard sprang from a shadowy ‘Old Guard’ which drew its funds directly from large banks, insurance companies, and other firms. Any plans of the cancellation of debt raised not the image of Australian self-determination but Bolshevist Communism. The capitalist class cynically manipulated the New Guard to its end of smashing the Lang government by any means necessary – by direct threats of force and through press hysteria. The New Guard brought New South Wales to the brink of civil war.

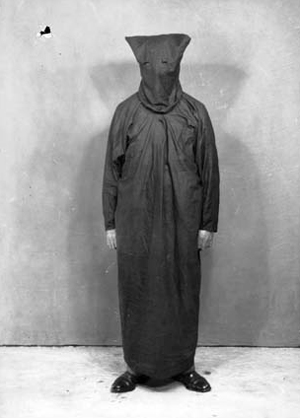

This economic disaster encouraged people to join political organisations that promised solutions to their problems. In New South Wales the two main organisations were the Australian Communist Party and the New Guard. These groups reflected the rise of communism and fascism in Europe and their ideas came to Australia with migrants. Many of the organisers in the trade unions were migrants from northern England and the intellectual left in Australia came from German Jews migrating from the persecution of the Nazis in the 1930s. Some New Guard branches took the black on red swastika flag of the German Nazis as their symbol and dress of the Klu Klux Klan in the southern United States of America.

The costume of an inner Fascist group in the New Guard, c.1930s. Courtesy National Archives of Australia

In May 1932′ Sir Philip Game, Governor of New South Wales, sacked the Lang government and ordered new elections. The New Guard automatically offered support to the United Australia Party. The conservative press painted Lang as a wild man manipulated by the Soviets and the Communist Party, and his government was defeated at the polls.

With the ‘Communist danger’ removed the New Guard rapidly declined and disappeared completely by 1935. It had done its job.

But Lang persisted. His meetings in 1931 and 1932 had been the largest ever seen in Australia. On one occasion, Sydney’s Moore Park was tightly packed and included folk who had walked to Sydney from Bathurst. The slogan “Lang is right” had become the watchword of Sydney’s unemployed. In 1933 Lang further developed his ideas on finance; he came to advocate views which took the best from Social Credit and pushed for the socialisation of credit, i.e. using the Reserve Bank to provide funds for capital creation and for stimulating consumer demand. He spoke more than ever as a nationalist against the demands of international capital.

However, improvements in the unemployment rate which was still high even in 1939 removed the possibility of Lang’s return to office. The politicians pulled Australia out of the Depression by the deprivations and burden of working men and women.

By the late 1930s, the economy started to recover with people getting jobs and factories producing more goods. But the Great Depression had produced a lot of suffering and had important effects for Australia. Between 1930 and 1939, Australia’s development almost stopped. The productivity of farming and industry declined. There was almost no migration to Australia and fewer babies were born between these years. Many people had lost faith in the Australian Government’s ability to manage the economy.

The Starvation Debenture is political election propaganda for the United Country Party for the June 1932 New South Wales State Government election. In 1932, the Country Party was led in New South Wales by M F Bruxner, in alliance with the United Australia Party led by Bertram Stevens, who became Premier after the June election.

The Starvation Debenture features the hammer and sickle emblem in a circle at centre top, and “ONE LANG” printed in squares in each corner, “Starvation Debenture” is printed across the top to foot blame for the Depression to the three caricatures, Premier Jack Lang, union leader Jock Garden, and an unidentified politician possibly Theodore the Federal Treasurer who was at odds with Lang, are printed in circles beneath this, accompanied by a printed caption criticising the Lang government, the text on the reverse side consists of further criticisms, particularly regarding Lang’s loan `repudiation’ policy, and urges support for the United Country Party: “Help United Country Party Candidates to Snip the Latch on Lang on June 11′. The United Country Party was the forerunner of the present National Party.

The Starvation Debenture has historic significance as evidence of conflicts between the Australian Communist Party and the New Guard in Australian politics and communities. The growth of these groups reflected the rise of communism and fascism in Europe and these ideas that came to Australia with migrants.

The Starvation Debenture has aesthetic significance in the design of 1930′s Depression era election propaganda.

The Starvation Debenture has intangible significance as a reminder of the experience of the stigma and chaos of the Depression. The trauma experienced by communities in the battles between socialism and fascism in Europe, America and Australia.

The Starvation Debenture is well provenanced. The certificate was the property of Mr William Butler of North Mackay Queensland, who donated it to the Powerhouse Museum in December 1993.

The Starvation Debenture represents a time when Australia saw itself as a predominantly British culture. The Australian government assisted the migration of nearly 200,000 people from Europe, while maintaining the White Australia Policy and the Immigration Restriction Act to keep Asian and Pacific Islanders out. New political ideas were coming to Australia from migrants from Europe. These ideas included fascism and socialism. These ideas were embraced by some as solutions to the growing racial and economic problems facing the world after World War One. To conservatives it was a direct threat to Australia’s links to the past of protection and governance by Britain and British class structures.

The interpretive potential of the Starvation Debenture is considerable. The Starvation Debenture interprets a time when European migrants brought with them political philosophies that would in turn shape the political debate and culture of Australia.

Footnotes

Bibliography

Heritage Office & Dept of Urban Affairs & Planning 1996, Regional Histories of NSW, Sydney.

Heritage Collections Council 2001, Significance: A guide to assessing the significance of cultural heritage objects and collections, Canberra

Websites

index.php?irn=141668&search=debenture&images=&c=&s=

Migration Heritage Centre

October 2007 – updated 2011

Crown copyright 2007©

The Migration Heritage Centre at the Powerhouse Museum is a NSW Government initiative supported by the Community Relations Commission.

www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au

Regional Services at the Powerhouse Museum is supported by Movable Heritage, NSW funding from the NSW Ministry for the Arts.