Era: 1840 - 1900 Cultural background: Chinese Collection: Riverina Theme:Agriculture Blacksmiths Immigration Restiction Labour Movement Riots Settlement

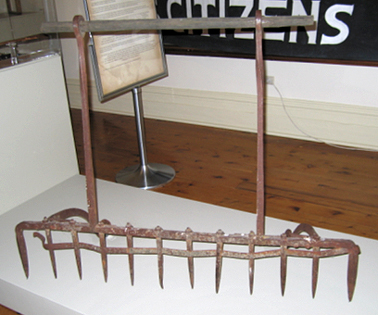

Chinese harrow, c.1860-70s. Photograph Stephen Thompson

Chinese harrow, c.1860-70s. Photograph Stephen ThompsonCollection

Museum of the Riverina, Wagga Wagga, Australia.

Object Name

Chinese Harrow.

Object/Collection Description

Harrow. Wrought Iron. Dimensions: approximately 700mm high x 1000mm wide x 70mm deep.

The discovery of gold in New South Wales from the early 1850s saw a huge influx of migrants in search of instant wealth. The primary result of the Gold Rush was that the economy boomed and, for a short time, gold outstripped wool as the Colony’s primary export. Many of the people who came in search of gold were Chinese men. Drawn from their home villages (mainly in Kwangtung) by the first gold rushes in Victoria, California and New South Wales in the 1850s, they usually arrived in organised groups of 30 to 100 men. In 1861 there were about 13,000 Chinese in New South Wales with the majority (12,200) on the goldfields. Throughout the 19th century, Chinese arrivals continued to the mining regions of New South Wales, replacing those who had returned home or left for opportunities elsewhere.

The Chinese diggers moved from goldfield to goldfield within New South Wales and across the border. Constantly on the move, their presence and experience are evidenced mainly from the observations and interpretation of Anglo-Australians, from archaeological digs and from objects saved by families and community members. There are few written accounts and sources from a Chinese perspective. The Chinese attracted particular attention and local newspapers were quick to comment on their distinctive features, clothes, languages and habits – especially their tendency to travel en masse – their methods of transport, their diligence, tirelessness and productivity. Any admiration of their work ethic was offset by envy and resentment when times got hard. The Chinese were often scapegoated by disgruntled Anglo diggers as seen in the violent anti-Chinese riots at Turon (1853), Meroo (1854) Rocky River (1856) Tambaroora (1858) Lambing Flat, Kiandra and Nundle (1860 and 1861) and Tingha tin fields (1870). They were seen initially as oddities, later as rivals and then as threats to white Australia.

In the Riverina and western New South Wales several thousand Chinese men left the diggings and were employed in land clearing, market gardening and general labouring. The cleared land was used for wheat growing and sheep grazing, and the men lived in camps outside towns and on pastoral properties. A detailed report of the five largest camps was prepared in 1883 by Martin Brennan, the New South Wales Sub-Inspector of Police, and Quong Tart, who was at that time New South Wales’s leading Chinese businessman and most respected citizen. The total Chinese population of the camps was 869. The largest camps were located at Narrandera and Wagga Wagga, Deniliquin, Hay and Albury.

Chinese market gardens, c.1901. Courtesy State Library of Victoria

The Brennan Report was prompted by public concerns surrounding the perceived widespread Chinese problem of opium smoking and poor hygiene. At Narrandera, the land was leased by two Chinese men, who sub-let it to other Chinese. There were 340 people at the camp that included 12 gardeners, 124 labourers, and 64 cooks and a number of store keepers, owners of gambling or opium houses. The population was much larger when the men returned from their labouring work on the sheep runs. The camp was surrounded by a palisade with an orchard and several hectares of vegetables. Most of the camp was owned by Sam Yett.

Chinese camps and land clearing were not confined to the larger Riverina towns. There was a large Chinese camp on Conapaira station near Rankin Springs north of Narrandera. North of Rankin Springs at Euabalong there were Chinese market gardens and at least one joss house, thus suggesting that there must have been a large camp in that area. There were also camps at the towns of Mossgiel and Darlington Point further west. At Darlington Point the Chinese garden was well irrigated and a commercial success. All the camps and gardens had the hallmarks of Chinese gardens- harrowed fields, orchards, wells and an extensive canal networks.

A Chinese camp and market gardens were also located on the banks of the Lachlan River at Hillston about 100 km north of Griffith. One of the earliest accounts of these gardens resulted from the aftermath of a brawl between the Chinese and Europeans in 1895. On the day following Chinese New Year a number of Europeans visited the garden, known as Chong Lees, which adjoined a camp where 30 or 40 Chinese lived. Another garden, owned by Harry Fong You was located across the river. The visitors were well treated at Chong Lees, but some of the more drunk men began to pull fruit from the trees. Protests of the Chinese gardeners were ignored and a fight broke out. About 30 Chinese and 20 Europeans were involved in the brawl. One Chinese man was killed and three severely wounded. Ten Europeans were brought to trial, but they were all acquitted of manslaughter. 1

At the Hillston gardens the Chinese raised water from the river by small buckets holding about two litres, which were fastened to an endless chain driven by one horse going round and round continuously. The Chinese farmers flood irrigated some of their vegetables and fruit trees. But much of the water was run down a channel to ponds of about 1350 litres capacity. From there the water was taken to the plants in two large watering cans carried on a shoulder yoke. The method of raising water from the Lachlan River has strong similarities to that described by Franklin King in his 1911 account of farming in China, Korea and Japan, although a treadmill was not used.

Without scrub-cutting, an extensive and labour-intensive activity, there would have been far fewer Chinese in the region and nowhere near as many gardens. By any measure the amount of cleared land was enormous. For instance, in 1890 the manager of Coan Downs, a property of about 96,000 hectares north of Hillston, remarked that if it had not been for the Chinese labourers the station would never have been cleared, and that as a consequence he had cleared more land than any other station in the neighbourhood, increasing the stock carrying capacity enormously. Land clearing work was negotiated between the landowners and Chinese contractors. Food, equipment, other provisions and transport were supplied by Chinese merchants in towns such as Narrandera and Wagga Wagga. Some of the market gardeners would have also worked on the land clearing contracts, though most were engaged in gardening full time.

The riots at Hillston are a reminder that racial conflict was not confined to the goldfields. However, this particular incident should possibly be seen more as an isolated fight, unusual for a rural town, and one over which the police had little immediate control. Otherwise almost all other incidents that have been documented are the usual array of taunts, cowardly assaults and bullying. The assaults were dealt with in the courts, the magistrates and the press often reminding the townspeople that regardless of what they may think of the Chinese as a group, as individuals they were entitled to the same legal protection and penalties as everyone else.2

Despite these tensions, the Chinese were very highly regarded as market gardeners, an activity in which they were not usually in direct competition with Europeans. The same considerations applied to their employment as scrub cutters and landclearers. In 1890 a correspondent for the Sydney Morning Herald stated that the Chinese were highly sought after in the latter occupations. It was not so much because they worked for less, for in many cases they got the same wages or even more than European workers; it was because they were regarded as steadier and more reliable. As cooks and gardeners the Chinese were invaluable and they produced nearly all the vegetables grown in the bush. They could also turn their hand to rabbiting and were found ready to do nearly all the rough work on the stations. In Wagga Wagga the Chinese were renowned for their generous contributions to the hospital and local churches, and events such as the opening of the new ‘joss house’ in 1887 and celebration of the Chinese New Year attracted many Europeans. 3

Despite the early anti Chinese riots on the gold fields, it appears that from the 1860s the racial situation on the southern and western New South Wales rural districts had become more tolerant and accepting. The Chinese were noted for their lawfulness and generosity in local causes, and were an accepted part of everyday life. They were not in threatening occupations and served an important economic function in opening up the land.

The Chinese were important pioneers in the Riverina and western New South Wales, with large scale activities and large numbers involved. The frontier was moving sharply northwards during the 1880s, prompted in part by a boom in copper mining activity. Cobar was the largest town, but it was closely followed by Nymagee, Mount Hope, Shuttleton and the gold mining settlements at Gilgunnia, Mount Allen, Mount Drysdale and Canbelego. The miners and their families provided a market for produce of many of the pastoralists, who in turn, needed to clear the land to increase their stock carrying capacity. Everyone needed fresh fruit and vegetables. Chinese market gardeners and land clearers were essential to these developments.

The Chinese gardeners made and used various improvised and traditional agricultural tools. Harrows were used by market gardeners to cultivate the surface of the soil. In this way it is distinct in its effect from the plough, which is used for deeper cultivation. Harrows were originally horse-drawn. This harrow was used in the Wagga Wagga area by Chinese market gardeners.

Harrowing is often carried out on fields to follow the rough finish left by ploughing operations. The purpose of this harrowing is generally to break up clods and lumps of soil and to provide a finer finish, a good tilth or soil structure that is suitable for seeding and planting operations. Harrowing may also be used in farming to remove weeds and to cover seed after sowing. In modern sports grounds maintenance a light chain harrowing is often used to level off the ground, after heavy use, to remove and smooth out boot marks and indentations.

Harrows may be of several types and weights, depending on the intended purpose. They almost always consist of a rigid frame to which are attached disks, teeth, linked chains or other means of cultivation. In the colder climates the commonest types are the disk harrow and the chain harrow but in New Zealand and Australian dairy areas the tine harrow is common. Chain harrows are often used for lighter work such as levelling the tilth or covering seed, while disk harrows are typically used for heavy work, such as following ploughing to break up the sod.

The harrow historic significance lies in the Chinese relationship to the themes of the Gold Rushes experience, market gardens, racial antagonism and fear of the exotic and unknown, Australia’s links to Britain and the development of racial discrimination policies after Federation.

The Harrow has aesthetic significance relating to the design and manufacture of 19th century improvised agricultural tools otherwise known as ‘bush tools’.

The harrow provides a research tool for historians to explore the culture of the Chinese on the market garden in regional New South Wales. The harrow is evidence of the closed culture and forced isolation of the Chinese on the diggings, working the market gardens and hawking. The ‘different-ness’ of Chinese culture and practices and success of the miners and market gardeners was later were used as evidence on which to base hysterical racial slurs against the Chinese in order to further isolate, victimise and drive them out of the camps or townships. These slurs provided the basis for the racist logic of the White Australia Policy. While there was racist undercurrents in the wider Australian community and in government legislation, in the communities where the Chinese had gardens and shops the racial situation had become more tolerant and accepting.

The Chinese in regional New South Wales are predominately related to the early migrants to the goldfields and the later market gardeners and grocers. The Harrow has an intangible significance for these communities to recognise and acknowledge their ancestors and to rise above the inherent racism that was dealt out to the 19th century diggers.

The harrow was donated to the Museum of the Riverina and has been in the collection ever since.

The harrow is quite rare because a lot of the material culture of the Chinese on the goldfields either ended up in mine tailings or rubbish holes or was simply scavenged for scrap iron or destroyed. It is rare to have a harrow provenanced to regional market garden in a museum collection. An extended collection of material related to the Chinese on the goldfields and market gardens is in museums and private collections across regional New South Wales.

The harrow represents the culture and traditions of the Chinese miners and later gardeners. They are evidence of the culture and practices they brought with them to New South Wales. The harrow is evidence of the resourcefulness of Chinese miners and gardeners.

The condition of the harrow is excellent given the rarity and fragile nature of the fabric. It is significant that such objects remain in good condition, intact and in the region they have an historical association with.

The harrow is a powerful interpretive tool in communicating the experiences and the treatment of the Chinese on the diggings and market gardens in regional New South Wales.

Footnotes

2 The Riverina Grazier, 1 June, 13 August 1881, 18 January, 14 June 1882.

3 Sydney Morning Herald, 30 December 1890; Sherry Morris, ‘The Chinese Quarter in Wagga Wagga in the 1889s’, Newsletter of the Wagga Wagga and District Historical Society Inc, no. 276 (June-July 1992), pp.5-6.

Bibliography

McGowan, B 2005, Chinese market gardens in southern and western New South Wales,School of Archaeology and Anthropology, Australian National University, Canberra.

Heritage Office & Dept of Urban Affairs & Planning 1996, Regional Histories of NSW, Sydney.

Heritage Collections Council 2001, Significance: A guide to assessing the significance of cultural heritage objects and collections, Canberra.

Wilton, J 2004, Golden Threads: The Chinese in Regional NSW, 1850 – 1950, New England Regional Museum & Powerhouse Museum Publishing.

Migration Heritage Centre

June 2007

Crown copyright 2007©

The Migration Heritage Centre at the Powerhouse Museum is a NSW Government initiative supported by the Community Relations Commission.

www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au

Regional Services at the Powerhouse Museum is supported by Movable Heritage, NSW funding from the NSW Ministry for the Arts.

The Museum of the Riverina is supported by the City of Wagga Wagga and the NSW Ministry for the Arts.

www.arts.nsw.gov.au